|

Armenians in Baku

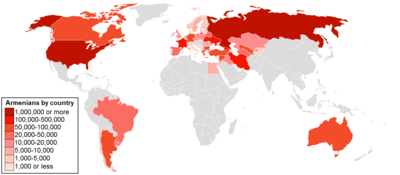

Armenians once formed a sizable community in Baku, the current capital of the Republic of Azerbaijan. Though the date of their original settlement is unclear, Baku's Armenian population swelled during the 19th century, when it became a major center for oil production and offered other economic opportunities to enterprising investors and businessmen. Their numbers remained strong into the 20th century, despite the turbulence of the Russian Revolutions of 1917, but almost all the Armenians fled the city between 1988 and January 1990.[7] By the beginning of January 1990, only 50,000 Armenians remained in Baku compared to a quarter million in 1988; most of these left after being targeted in a pogrom that occurred before the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the early stages of the first Nagorno-Karabakh War.[8] History  Pre-Russian RevolutionLater, in the 7th-century Armenian philosopher, mathematician, geographer, astronomer and alchemist Anania Shirakatsi in his most famous work Ashkharhatsuyts (Geography) listed Alti-Bagavan as one of the 12 districts of the Province Paytakaran (one of the 15 Provinces of Armenia), which linguist and orientalist Kerovbe Patkanov in his translation identifies as Baku.[9] Orientalist and academician Vasily Bartold referring to the 15th-century Persian historian Hamdallah Mustawfi, speaks about the existence of an old Armenian church in Baku[10] and the 15th-century Arab geographer Abdar-Rashid al- Bakuvi in his writings mentions that the majority of the population of Baku (Bakuya) were Christian.[11] Baku saw a large influx of Armenians following the city's incorporation into the Russian Empire in 1806. Many took up jobs as merchants, industrial managers and government administrators.[12] Armenians established a community in the city with churches, and schools, and was the scene of a lively literary culture. The favorable economic conditions provided by the Imperial Russian government allowed many Armenians to enter the burgeoning oil production and drilling business of Baku. Armenians along with Russians constituted the financial elite of the city and local capital was concentrated mainly in their hands. The Armenians were the second most numerous group in the judiciary.[13] By 1900, Armenian-owned businesses formed nearly one-third of the oil companies operating in the region.[14] The growing tension between Armenians and Azeris (often instigated by the Russian officials who feared nationalist movements among their ethnically non-Russian subjects) resulted in mutual pogroms in 1905–1906, planting the seed of distrusts between these two groups in the city and elsewhere in the region for decades to come.[15][16] Independent AzerbaijanFollowing the proclamation of Azerbaijan's independence in 1918, the Armenian nationalist Dashnaktsutyun Party became increasingly active in the then Bolshevik-occupied Baku. There were, according to Russian statistics, at this time 120,000 Armenians living in the Baku Province.[17] Several members of the governing body of the Baku Commune consisted of ethnic Armenians. On April 1 1918, after the Ottoman forces had launched their Transcaucasian campaign in February, clashes broke out between various factions of the city. Despite the efforts of Stepan Shaumian, the Armenian head of the Baku Commune to forge an alliance between Bolshevik, Armenian, and Muslim factions, the alliance soon fell apart.[18] Situation escalated when the Muslims, alarmed by the growing power of the Armenians, tried to seek help from outside, inviting the former tsarist all-Muslim Savage division into the city.[19] This caused alarm in the city, and soon the civilian fighting between the factions broke out. Despite the Armenian efforts to stay neutral and be ready only for self-defence, soon a decision was made to join the forces with the Bolsheviks to resist the Muslim military attack. The fighting resulted in the victory of the Armenian-Bolshevik coalition, which left thousands of casualties from both sides, among which many were Muslims (3000 according to the estimates of Shaumian, and 12000 according to the Azerbaijani sources).[20] Five months later, the Armenian community itself dwindled as thousands of Armenians either fled Baku or were massacred at the approach of the Turkish–Azeri army (which seized the city from the Bolsheviks).[21] Regardless of these events, on 18 December 1918, ethnic Armenians (including members of the Dashnaktsutyun) were represented in the newly formed Azerbaijani parliament, constituting 11 of its 96 members.[22] Soviet eraFollowing the Sovietisation of Azerbaijan, Armenians managed to reestablish a large and vibrant community in Baku made up of skilled professionals, craftsmen and intelligentsia and integrated into the political, economic and cultural life of Azerbaijan. The community grew steadily in part due to the active migration of Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians to Baku and other large cities. The mainly-Armenian populated quarter of Baku called Ermenikend grew from a tiny village of oil workers into a prosperous urban community.[23] At the outset of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in 1988, Baku alone had a larger Armenian population than Nagorno-Karabakh.[24] Armenians were widely represented in the state apparatus.[25] The multi-ethnic nature of Soviet-era Baku created the conditions for the active integration of its population and the emergence of a distinct Russian-speaking urban subculture, to which ethnic identity began losing ground and with which post-World War II generations of urbanized Bakuvians regardless of their ethnic origin or religious affiliations tended to identify.[26][27] By the 1980s, the Armenian community of Baku had become largely Russified. In 1977, 58% of Armenian pupils in Azerbaijan were receiving education in Russian.[28] While in the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, Armenians often chose to disassociate themselves from Azerbaijan and Azeris, cases of mixed Azeri–Armenian marriages were quite common in Baku.[29] Pogrom and mass exodusThe political unrest in Nagorno-Karabakh remained a rather distant concern for Armenians of Baku until March 1988, when the Sumgait pogrom took place.[30] The anti-Armenian feelings were aroused because of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh resulting in the exodus of most Armenians from Baku and elsewhere in the republic.[31] However, many Armenian refugees from Azerbaijan later reported that despite ethnic tensions taking place in Nagorno-Karabakh, the relationships with their Azeri friends and neighbors had been unaffected.[32] The massacre in Sumgait came as a shock to both Armenian and Azerbaijanis of the cities, and many Armenian lives were saved as ordinary Azeris sheltered them during the pogroms and volunteered to escort them out of the country, often risking their own lives.[33][34] In some cases, the Armenians who were leaving entrusted their houses and possessions to their Azeri friends.[32] The Baku pogrom,[35][36] which broke out on 12 January 1990, lasted for seven days during which many Armenians were beaten, tortured or murdered, and their apartments were raided, robbed or burned, resulting in the flight of almost all of the Armenians from the city and marked the effective end of the Armenian community of Baku. Non-official sources estimate that the number of Armenians living on Azerbaijani territory outside Nagorno-Karabakh is around 2,000 to 3,000, and almost exclusively comprises persons married to Azeris or of mixed Armenian-Azeri descent.[37] The number of Armenians who are likely not married to Azeris and are not of mixed Armenian-Azeri descent are estimated at 645 (36 men and 609 women) and more than half (378 or 59 per cent of Armenians in Azerbaijan outside Nagorno-Karabakh) live in Baku and the rest in rural areas. They are likely to be elderly and sick, and probably have no other family members.[37] Economic life The discovery of oil in Baku in the mid-19th century attracted a large number of Armenians to the city. In 1871, the first successful well was drilled by Ivan Mirzoev, an ethnic Armenian.[14] He was followed by oil tycoon Alexander Mantashev, whose A.I. Mantashev and Co. trading house opened branches in major cities in Europe and Asia and established majority control (51.3%) over the total stock of oil and an overwhelming majority (66.8%) of the oil content in the Caspian Sea. He financed the construction of an east–west pipeline which extended 500 miles from Baku to the Black Sea port of Batumi.[38] With rising competition against the Nobel Brothers and the Rothschilds, the A. I. Mantashev and Co. ultimately merged with several other Russian companies to form the Russian General Oil Company (OIL) in 1912. OIL eventually bought several oil production companies in Baku, including Mirzoev Brothers and Co., A. S. Melikov and Co., the Shikhovo (A. Tsaturyan, G. Tsovianyan, K. and D. Bikhovsky, L. Leytes), I. E. Pitoev and Co., Krasilnikov Brothers, Aramazd and others.[39] The prominent Armenian businessman and philanthropist Calouste Gulbenkian also began to build ties and invest heavily in the Baku oil industry, the fortunes he made there being the source for his nickname of "Mr. Five Percent."[40] Other notable Armenian businessmen in the oil industry in Baku included Stepan Lianozyan (owner of G.M. Lianozov Sons, which became one of the largest oil industry firms in Russia),[39] the Adamov Brothers (of A. Y. Adamoff Brothers; M. Adamoff, the eldest of the brothers, went on to become one of the wealthiest men in Baku),[41] and A. Tsaturyan, G. Tumayan and G. Arapelyan, who were proprietors of A. Tsaturov & Co., which was later bought out by Mantashev. Around 1888, out of the 54 oil companies in Baku, only two major oil companies were Azeri owned.[42] Out of the 162 oil refineries, 73 were Azeri owned but only seven of them had more than fifteen workers.[42] Other Armenians in Baku tended to enter the workforce as foremen and white-collar employees.[14] Culture Baku's Armenian community grew alongside the city's development through the course of the 19th century. The large-scale construction and expansion of the city attracted numerous Russian and Armenian architects, many of whom had received their education in Russia (in particular, Saint Petersburg) or other parts of Europe. Prominent Armenian architects included Hovhannes Katchaznouni, Freidun Aghalyan, Vardan Sarkisov, and Gavriil Ter-Mikelov. Many of the buildings they designed, influenced by Neo-Classical themes then popular in Russia and also styles and motifs taken from medieval Armenian Church Architecture, still stand today.[citation needed] Among the most well-known examples are the Azerbaijan State Philharmonic Hall and the Commercial College of Baku (both designed by Ter-Mikelov). There were three Armenian churches in Baku, but they were demolished or closed down following the establishment of Soviet power in 1920. The Saint Thaddeus and Bartholomew Cathedral, built in 1906–1907, was destroyed in the 1930s, as part of Stalin's atheist policies. The Church of the Holy Virgin, which had not been functioning since 1984 due to falling in severe disrepair, was demolished in the early 1990s.[43] The St. Gregory Illuminator Church was set aflame during the pogrom of 1990,[44] but was restored in 2004 during a renovation and was transformed into the archive department of the Department of Administration Affairs of the Presidential Administration of Azerbaijan.[45] During the Imperial Russian period, the community enjoyed a vibrant literary culture, as seen in the publication of dozens of Armenian-language newspapers, journals, and magazines. The first Armenian periodical to be published in Baku, in 1877, was Haykakan Ashkharh (The Armenian World), a literary and pedagogic journal established and edited by Stephannos Stephaney, while other popular Armenian periodicals included Aror (The Plough), an illustrated calendar published from 1893–1896, Sotsial Demokrat (The Social-Democrat), an economic-political-public journal, with editors V. Marsyan and Lazo at its helm, Banvori Dzayn (The Voice of the Laborer, 1906, with Sarkis Kasyan as the editor), and Lusademin (At the Dawn), a literary collection published from 1913-14 by A. Alshushyan.[46] Also the Armenian Community of Baku built the first Philanthropic Society of Azerbaijan, maintaining the then-richest library of Transcaucasia,[47] but then was shut down by the Soviet Government. Armenian districtErmenikend[48] (Armenian: Արմենիքենդ; Azerbaijani: Ermənikənd; Russian: Арменикенд, literally "Armenian village" in Azerbaijani) was a district located in the Nasimi raion of Baku, where many Armenians lived.[48] The settlement was developed in the 1920s on the sparsely populated outskirts of Baku as one of the earliest Soviet experiments in the integrated development of a large urban area.[49] The village of Ermenikend existed in Baku in 1918 when 15,000 Armenians were killed during the September Days.[50] The reconstruction and modernization of Ermenikend started later, when Baku further expanded, when Azerbaijan, after a brief period of independence as the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan during 1918–1920 with the collapse of Czarist Russia (and also Armenia which went through the same brief stage as well) was invaded and annexed by the Soviet Union as the newly formed Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic in 1920. The former suburb Ermenikend has been transformed into a model town consisting exclusively of new blocks.[51] Several famed Constructivist architects worked on the Ermenikend model village, which started in 1925.[52] The settlement became part, with the steady expansion of the city of Baku. Officially the district was part of a larger district named "Shahumyan" after the Armenian Bolshevik leader Stepan Shaumyan who lived in Baku, while the name of Ermenikend always was mentioned next to it.[53] Ermenikend was designed to be the home of oil workers. The Soviet architects Samoylov A.V. and Ivanitsky A.P supervised the architecture of Ermenikend in the 1920–1930s.[54] The central part had 3–4 storied buildings in the style of Soviet socialist realist architecture (near the Mughan hotel). Connected by tram lines with the coastal part of Baku, Ermenikend quickly became one of the main parts of the city.[55] With the influx of many other nationalities and with the dispersal of the Armenian community to other districts of the city, the district lost this distinction and the nickname gradually disappeared. Until the 1980s, the Armenians in Baku were concentrated in Ermenikend, and it was known for this.[56][57] After the Armenian pogroms on 13–20 January 1990, the enclave came to end, when the Armenian community of Baku fled the country. Notable natives

See alsoNotes

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||