|

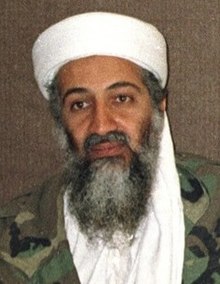

Bin Laden Issue Station

The Bin Laden Issue Station, also known as Alec Station, was a standalone unit of the Central Intelligence Agency in operation from 1996 to 2005 dedicated to tracking Osama bin Laden and his associates, both before and after the 9/11 attacks. It was headed initially by CIA analyst Michael Scheuer and later by Richard Blee and others. Scheuer had noticed an increase in activity by Bin Laden in Afghanistan and the rise of a new organization known as al Qaeda, and suggested this be the focus of the station's work. Soon after its creation, the Station developed a deadly vision of bin Laden's activities and its work came to include the planning of search and destroy missions. The CIA inaugurated a grand plan against al-Qaeda in 1999, but struggled to find the resources to implement it. At least 5 such missions were planned by Alec Station. The planning of these missions began to factor in the use of aerial drones. In 2000, a joint CIA-USAF project using Predator reconnaissance drones and following a program drawn up by the bin Laden Station produced probable sightings of the al-Qaeda leader in Afghanistan. Resumption of flights in 2001 was delayed by arguments over a missile-armed version of the aircraft. Only on September 4, 2001 was the go-ahead given for weapons-capable drones. The Station was wound down in 2005. Bin Laden was finally killed in 2011. Conception, birth and growthThe idea was born from discussions within the CIA's senior management, and that of the CIA's Counterterrorism Center (CTC). David Cohen, head of the CIA's Directorate of Operations, and others, wanted to try out a virtual station, modeled on the Agency's overseas stations, but based near Washington DC and dedicated to a particular issue. The unit "would fuse intelligence disciplines into one office—operations, analysis, signals intercepts, overhead photography and so on".[1] Cohen had trouble getting any Directorate of Operations officer to run the unit. He finally recruited Michael Scheuer, an analyst then running the CTC's Islamic Extremist Branch; Scheuer "was especially knowledgeable about Afghanistan". Scheuer, who "had noticed a recent stream of reports about Bin Laden and something called al Qaeda", suggested that the new unit "focus on this one individual"; Cohen agreed.[2]: 109 The Station opened in January 1996, as a unit under the CTC. Scheuer set it up and headed it from that time until spring 1999. The Station was an interdisciplinary group, drawing on personnel from the CIA, FBI, NSA, DIA and elsewhere in the intelligence community. Formally known as the Bin Ladin Issue Station, it was codenamed Alec Station after Scheuer's son's name, as referred to by DIA's Able Danger liaison Anthony Shaffer.[3] By 1999, the unit's staff had nicknamed themselves the "Manson Family", "because they had acquired a reputation for crazed alarmism about the rising al-Qaeda threat".[1] The Station originally had twelve professional staff members, including CIA analyst Alfreda Frances Bikowsky and former FBI agent Daniel Coleman.[4] This figure grew to 40–50 employees by September 11, 2001. (The CTC as a whole had about 200 and 390 employees at the same dates.)[1]: 319, 456 [2]: 109, 479, n.2 CIA chief George Tenet later described the Station's mission as "to track [bin Laden], collect intelligence on him, run operations against him, disrupt his finances, and warn policymakers about his activities and intentions". By early 1999 the unit had "succeeded in identifying assets and members of Bin Laden's organization ...".[5]: 4, 18 New view of al-Qaeda, 1996–1998Soon after its inception, the Station began to develop a new, deadlier vision of al-Qaeda. In May 1996, Jamal Ahmed al-Fadl walked into a US embassy in Africa and established his credentials as a former senior employee of bin Laden.[2]: 109 Al-Fadl had lived in the US in the mid-1980s, and had been recruited to the Afghan mujaheddin through the al-Khifa center at the Farouq mosque in Brooklyn. Al-Khifa was the interface of Operation Cyclone, the American effort to support the mujaheddin, and the Peshawar, Pakistan-based Services Office of Abdullah Azzam and Osama bin Laden, whose purpose was to raise recruits for the struggle against the Soviets in Afghanistan.[6] Al-Fadl had joined al-Qaeda in 1989, apparently in Afghanistan. Peter Bergen called him the third member of the organization (presumably after Azzam and bin Laden). But al-Fadl had since embezzled $110,000 from al-Qaeda, and now wanted to defect.[2]: 62 Al-Fadl was persuaded to come to the United States by Jack Cloonan, an FBI special agent who had been seconded to the bin Laden Issue Station. There, from late 1996, under the protection of Cloonan and his colleagues, al-Fadl "provided a major breakthrough on the creation, character, direction and intentions of al Qaeda". "Bin Laden, the CIA now learned, had planned multiple terrorist operations and aspired to more"—including the acquisition of weapons-grade uranium. Another "walk-in" source (since identified as L'Houssaine Kherchtou) "corroborated" al-Fadl's claims. "By the summer of 1998", Scheuer would write, "we had accumulated an extraordinary array of information on [al-Qaeda] and its intentions." He goes on:

And further:

First capture plan and US embassy attacks, 1997–98In May 1996, bin Laden moved from Sudan to Afghanistan. Scheuer saw the move as a (further) "stroke of luck". Though the CIA had virtually abandoned Afghanistan after the fall of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan in 1991, case officers had re-established some contacts while tracking down Kasi, the Pakistani gunman who had murdered two CIA employees in 1993. "One of the contacts was a group associated with particular tribes among Afghanistan's ethnic Pashtun community." The team, dubbed "TRODPINT" by the CIA, was provisioned with arms, equipment and cash by the CTC, and set up residence around Kandahar. Kasi was captured in June 1997. CTC chief Jeff O'Connell then "approved a plan to transfer the Afghans agent teams from the [CIA's] Kasi cell to the bin Laden unit". By autumn 1997, the Station had roughed out a plan for TRODPINT to capture bin Laden and hand him over for trial, either to the US or an Arab country. In early 1998 the Cabinet-level Principals Committee apparently gave their blessing, but the scheme was abandoned in the spring for fear of collateral fatalities during a capture attempt. In August 1998, militants truck-bombed the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. President Clinton ordered cruise-missile strikes on bin Laden's training camps in Afghanistan. But there was no "follow-up" action to these strikes.[1]: 371–6 [2]: 109–115 New leadership and a new plan, 1999 In December 1998, CIA chief Tenet "declared war" on Osama bin Laden.[1]: 436–7, 646, n.42 [2]: 357 Early in 1999, Tenet "ordered the CTC to begin a 'baseline' review of the CIA's operational strategy against bin Laden". In the spring he "demanded 'a new, comprehensive plan of attack' against bin Laden and his allies". As an evident part of the new strategy, Tenet removed Michael Scheuer from the leadership of the Bin Laden Station. Later that year Scheuer would resign from the CIA. Tenet appointed Richard Blee, a "fast-track executive assistant" who "came directly from Tenet's leadership group", to have authority over the Station. "Tenet quickly followed this appointment with another: He named Cofer Black as director of the entire CTC."[1]: 451–2, 455–6 [2]: 14, 142, 204 The CTC produced a "comprehensive plan of attack" against bin Laden and "previewed the new strategy to senior CIA management by the end of July 1999. By mid-September, it had been briefed to CIA operational level personnel, and to [the] NSA [National Security Agency], the FBI, and other partners." The strategy "was called simply, 'the Plan'."

Black also arranged for a CIA team, headed by Alec Station chief Blee, to visit Northern Alliance leader Ahmad Shah Massoud to discuss operations against bin Laden. The mission was codenamed "JAWBREAKER-5", the fifth in a series of such missions since autumn 1997.[1]: 466 The team went in late October 1999. After the meeting, Alec Station believed that Massoud would be a second source of information on bin Laden.[2]: 142

Tenet would testify that "by September 11, 2001, a map would show that these collection programs and human networks nearly covered Afghanistan."[5]: 17 Emergence of 9/11 hijackersBeginning in September 1999, the CTC picked up multiple signs that bin Laden had set in motion major terrorist attacks for the turn of the year. The CIA set in motion the "largest collection and disruption activity in the history of mankind", as Cofer Black later put it. The CTC focused in particular on three groups of al Qaeda personnel: those known to have been involved in terrorist attacks; senior personnel both outside and inside Afghanistan, e.g., "operational planner Abu Zubaydah"; and "Bin Ladin deputy Muhammad Atef".[1]: 495–6 [2]: 174–80 Amid this activity, in November and December 1999, Mohamed Atta, Marwan al-Shehhi, Ziad Jarrah and Nawaf al-Hazmi visited Afghanistan, where they were selected for the "planes operation" that was to become known as 9/11. Al-Hazmi undertook guerrilla training at al-Qaeda's Mes Aynak camp (along with two Yemenis who were unable to get US entry visas). The camp was located in an abandoned Russian copper mine near Kabul, and was for a time in 1999 the only such training camp in operation. Atta, al-Shehhi and Jarrah met Muhammad Atef and bin Laden in Kandahar, and were instructed to go to Germany to undertake pilot training.[2]: 155–8, 168 Tracking the "Brooklyn cell"At about this time the United States Special Operations Command-Defense Intelligence Agency (SOCOM-DIA) operation Able Danger identified a potential Qaeda unit, consisting of the future leading 9/11 hijackers Atta, al-Shehhi, al-Mihdhar and Nawaf al-Hazmi. It termed them the "Brooklyn cell", because of some associations with the New York borough. Evidently at least some of the men were physically and legally present in the United States, since there was an ensuing legal tussle over the "right" of "quasi-citizens" not to be spied on.[8][9] Tracking al-Hazmi and al-MihdharIn late 1999, the National Security Agency (NSA), following up information from the FBI's investigation of the 1998 US embassy attacks, picked up traces of "an operational cadre", consisting of Nawaf al-Hazmi, his companion Khalid al-Mihdhar and Nawaf's younger brother Salem, who were planning to go to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, in January 2000. Seeing a connection with the attacks, a CTC officer sought permission to surveil the men.[1]: 487–8 [2]: 181

Mark Rossini, "The Spy Factory"[10]

The CIA tracked al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar as they traveled to and attended the al-Qaeda summit in Kuala Lumpur during the first week of January 2000. "The Counterterrorist Center had briefed the CIA leadership on the gathering in Kuala Lumpur ... The head of the Bin Ladin unit [Richard] kept providing updates", unaware at first that the information was out-of-date.[citation needed] When two FBI agents assigned to the station, Mark Rossini and Doug Miller, learned that al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar had entry visas to the United States, they attempted to alert the FBI. CIA officials in management positions over the FBI agents denied their request to pass along this information to FBI headquarters.[10] Michael Scheuer would later deny this, instead blaming the FBI for not having a "useable computer system".[11] In March 2000, it was learned that al-Hazmi had flown to Los Angeles. The men were not registered with the State Department's TIPOFF list, nor was the FBI told.[2]: 181–2, 383–4 There are also allegations that the CIA surveilled Mohamed Atta in Germany from the time he returned there in January/February 2000, until he left for the US in June 2000.[12] Analysis of the CIA's withholding of informationAccording to Richard A. Clarke, National Coordinator for Security, Infrastructure Protection, and Counter-terrorism (counter-terrorism chief) 1998-2003, the decision to withhold from the FBI and from the White House the information that Khalid al-Mihdhar and Nawaf Al Hazmi, two Saudi Arabian nationals known at the time of their entry in 2000 into the United States to be associated with al-Qaeda, were living under their own names in Southern California, was made at the highest level of the CIA. According to Clarke, Director of CIA George Tenet called him at the White House several times a day and met with him in person every other day to discuss "in microscopic detail" intelligence about Al-Qaeda, yet Tenet never shared this important information about the entry into the U.S. and American whereabouts of these two Al-Qaeda operatives, who on 9/11 went on to participate in the hijacking of American Airlines Flight 77. Clarke reasoned that the only reason for the decision to fail to share this information may have been that the CIA was running the two Saudis in some secret CIA operation. The CIA's Alec Station learned of the presence in the U.S. of the two Al-Qaeda operatives by Spring 2000. Clarke was confident, however, that had the CIA shared this key information even as late as a week before 9/11, law enforcement could have rounded them up. This view is shared by Jack Cloonan, former manager at the FBI’s unit for tracking al-Qaida (Squad I-49) and several FBI agents.[13] Predator drone, 2000–2001In spring 2000, officers from the Bin Laden Station joined others in pressing for "Afghan Eyes", the Predator reconnaissance drone program for locating bin Laden in Afghanistan. In the summer, "The bin Laden unit drew up maps and plans for fifteen Predator flights, each lasting just under twenty-four hours." The flights were scheduled to begin in September. In autumn 2000, officers from the Station were present at Predator flight control in the CIA's Langley headquarters, alongside other officers from the CTC, and US Air Force drone pilots. Several possible sightings of bin Laden were obtained as drones flew over his Tarnak-Farms residence near Kandahar. Late in the year, the program was suspended because of bad weather.[1]: 527, 532 [2]: 189–90 Resumption of flights in 2001 was delayed by arguments over an armed Predator. A drone equipped with adapted "Hellfire" anti-tank missiles could be used to try to kill bin Laden and other Qaeda leaders. Cofer Black and the bin Laden unit were among the advocates. But there were both legal and technical issues. In the summer the CIA "conducted classified war games at Langley ... to see how its chain of command might responsibly oversee a flying robot that could shoot missiles at suspected terrorists"; a series of live-fire tests in the Nevada desert (involving a mockup of bin Laden's Tarnak residence) produced mixed results. Tenet advised cautiously on the matter at a meeting of the Cabinet-level Principals Committee on September 4, 2001. If the Cabinet wanted to empower the CIA to field a lethal drone, Tenet said, "they should do so with their eyes wide open, fully aware of the potential fallout if there were a controversial or mistaken strike". National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice concluded that the armed Predator was required, but evidently not ready. It was agreed to recommend to the CIA to resume reconnaissance flights. The "previously reluctant" Tenet then ordered the Agency to do so. The CIA was now "authorized to deploy the system with weapons-capable aircraft, but for reconnaissance missions only", since the host nation (presumably Uzbekistan) "had not agreed to allow flights by weapons-carrying aircraft".

After 9/11Shortly after 9/11, Michael Scheuer came back to the Station as special adviser. He stayed until 2004.[15] After the September 11 attacks, staff numbers at the Station were expanded into the hundreds. Scheuer claimed the expansion was a "shell game" played with temporary (and inexperienced) staff, and that the core personnel "remained at under 30, the size it was when Scheuer left office in 1999".[16] (As we have seen, professional staff numbers grew to 40 to 50 by the eve of 9/11.) After 9/11, "Hendrik V.", and later "Marty M.", were chiefs of Alec Station's Bin Laden Unit.[17] The Bin Laden Station was disbanded in late 2005.[18] Bin Laden was eventually located in Abbottabad, Pakistan and killed by the United States Naval Special Warfare Development Group, commonly known as SEAL Team 6 in Operation Neptune Spear on May 2, 2011.[19][20] See alsoReferences

Further reading

|