|

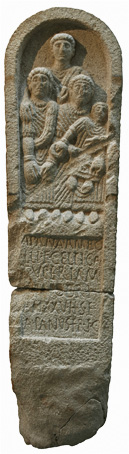

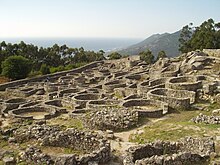

Gallaeci  The Gallaeci (also Callaeci or Callaici; Ancient Greek: Καλλαϊκοί) were a Celtic tribal complex who inhabited Gallaecia, the north-western corner of Iberia, a region roughly corresponding to what is now the Norte Region in northern Portugal, and the Spanish regions of Galicia, western Asturias and western León before and during the Roman period.[1][2] They spoke a Q-Celtic language related to Northeastern Hispano-Celtic, called Gallaecian or Northwestern Hispano-Celtic.[3][4] The region was annexed by the Romans in the time of Caesar Augustus during the Cantabrian Wars, a war which initiated the assimilation of the Gallaeci into Latin culture. The endonym of modern-day Galicians, galegos, derives directly from the name of this people. ArchaeologyArchaeologically, the Gallaeci evolved from the local Atlantic Bronze Age culture (1300–700 BC). During the Iron Age they received additional influences, including from Southern Iberian and Celtiberian cultures, and from central-western Europe (Hallstatt and, to a lesser extent, La Tène culture), and from the Mediterranean (Phoenicians and Carthaginians). The Gallaeci dwelt in hill forts (locally called castros), and the archaeological culture they developed is known by archaeologists as "Castro culture", a hill-fort culture (usually, but not always) with round or elongated houses.  The Gallaecian way of life was based in land occupation especially by fortified settlements that are known in Latin language as "castra" (hillforts) or "oppida" (citadels); they varied in size from small villages of less than one hectare (more common in the northern territory) to great walled citadels with more than 10 hectares sometimes denominated oppida, being these latter more common in the Southern half of their traditional settlement and around the Ave river. Due to the dispersed nature of their settlements, large towns were rare in pre-Roman Gallaecia although some medium-sized oppida have been identified, namely the obscure Portus Calle (also known as Cales or Cale; Castelo de Gaia, near Porto), Avobriga (Castro de Alvarelhos – Santo Tirso?), Tongobriga (Freixo – Marco de Canaveses), Brigantia (Bragança?), Tyde/Tude (Tui), Lugus (Lugo) and the Atlantic trading port of Brigantium (also designated Carunium; either Betanzos or A Coruña). This livelihood in hillforts was common throughout Europe during the Bronze and Iron Ages, getting in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, the name of 'Castro culture" (Castrum culture) or "hillfort's culture", which alludes to this type of settlement prior to the Roman conquest. However, several Gallaecian hillforts continued to be inhabited until the 5th century AD.  These fortified villages tended to be located in the hills, and occasionally rocky promontories and peninsulas near the seashore, as it improved visibility and control over territory. These settlements were strategically located for a better control of natural resources, including mineral ores such as iron. The Gallaecian hillforts and oppidas maintained a great homogeneity and presented clear commonalities. The citadels, however, functioned as city-states and could have specific cultural traits. The names of such hill-forts, as preserved in Latin inscriptions and other literary sources, were frequently composite nouns with a second element such as -bris (from proto-Celtic *brixs), -briga (from proto-Celtic *brigā), -ocelum (from proto-Celtic *okelo-), -dunum (from proto-Celtic *dūno-) all meaning "hill > hill-fort" or similar: Aviliobris, Letiobri, Talabriga, Nemetobriga, Louciocelo, Tarbucelo, Caladunum, etc. Others are superlative formations (from proto-Celtic *-isamo-, -(s)amo-): Berisamo (from *Bergisamo-), Sesmaca (from *Segisamo-). Many Galician modern day toponyms derive from these old settlements' names: Canzobre < Caranzovre < *Carantiobrixs, Trove < Talobre < *Talobrixs, Ombre < Anobre < *Anobrixs, Biobra < *Vidobriga, Bendollo < *Vindocelo, Andamollo < *Andamocelo, Osmo < Osamo < *Uxsamo, Sésamo < *Segisamo, Ledesma < *φletisama...[5] Associated archaeologically with the hill forts are the famous Gallaecian warrior statues - slightly larger than life size statues of warriors, assumed to be deified local heroes.  Political-territorial organizationThe Gallaecian political organization is not known with certainty but it is very probable that they were divided into small independent chiefdoms who the Romans called populus or civitas, each one ruled by a local petty king or chief (princeps), as in other parts of Europe. Each populus comprised a sizeable number of small hillforts (castellum). So each Gallaecian considered themselves a member of his or her populus and of the hillfort where they lived, as deduced by their usual onomastic phormula: first Name + patronymic (genitive) + (optionally) populus or nation (nominative) + (optionally) origin of the person = name of their hill-fort (ablative):

Gallaeci tribes

The list of Gallaeci tribes sorted by minority groups:

Pomponius Mela, who described the Galician seashore and their dwellers around 40 AD, divided the coastal Gallaeci in non-Celtic Grovii along the southern areas; the Celtic peoples who lived along the Rías Baixas and Costa da Morte regions in northern Galicia; and the also Celtic Artabri who dwelled all along the northern coast in between the latter and the Astures. Origin of the nameThe Romans named the entire region north of the Douro, where the Castro culture existed, in honour of the castro people that settled in the area of Calle — the Callaeci. The Romans established a port in the south of the region which they called Portus Calle, today's Porto, in northern Portugal.[6] When the Romans first conquered the Callaeci they ruled them as part of the province of Lusitania but later created a new province of Callaecia (Greek: Καλλαικία) or Gallaecia. The names "Callaici" and "Calle" are the origin of today's Gaia, Galicia, and the "Gal" root in "Portugal", among many other placenames in the region. Gallaecian languageGallaecian was a Q-Celtic language or group of languages or dialects, closely related to Celtiberian, spoken at the beginning of our era in the north-western quarter of the Iberian Peninsula, more specifically between the west and north Atlantic coasts and an imaginary line running north–south and linking Oviedo and Mérida.[7][8] Just like it is the case for Illyrian or Ligurian languages, its corpus is composed by isolated words and short sentences contained in local Latin inscriptions, or glossed by classic authors, together with a considerable number of names – anthroponyms, ethnonyms, theonyms, toponyms – contained in inscriptions, or surviving up to date as place, river or mountain names. Besides, many of the isolated words of Celtic origin preserved in the local Romance languages could have been inherited from these Q-Celtic dialects. Gallaecian deities Through the Gallaecian-Roman inscriptions, is known part of the great pantheon of Gallaecian deities, sharing part not only by other Celtic or Celticized peoples in the Iberian Peninsula, such as Astur — especially the more Western — or Lusitanian, but also by Gauls and Britons among others. This will highlight the following:

History

The fact that the Gallaeci did not adopt writing until contact with the Romans constrains the study of their earlier history.[citation needed] However, early allusions to this people are present in ancient Greek and Latin authors prior to the conquest, which allows the reconstruction of a few historical events of this people since the second century BC.[citation needed] The oldest known inscription referring to the Gallaeci (reading Ἔθνο[υς] Καλλαϊκῶ[ν], "people of the Gallaeci") was found in 1981 in the Sebasteion of Aphrodisias, Turkey, where a triumphal monument to Augustus mentions them among other fifteen nations allegedly conquered by this Roman emperor.[9] Protected by their mountainous country and its isolation, the Gallaican tribes did not fall under Carthaginian rule, though a combined Gallaeci-Lusitani mercenary contingent led by a chieftain named Viriathus (not to be confused with the later Lusitani general bearing the same name that battled the Romans in Hispania in the mid-2nd century BC) is mentioned in Hannibal's army during his march to Italy during the Second Punic War, participating in the battles of Lake Trasimene and Cannae.[10] On his epic poem Punica, Silius Italicus gives a short description of these mercenaries and their military tactics:[11]

The Gallaeci came into direct contact with Rome relatively late, in the wake of the Roman punitive campaigns against their southern neighbours, the Lusitani and the Turduli Veteres. Regarded as hardy fighters,[12] Gallaeci warriors fought for the Lusitani during Viriathus' campaigns in the south,[13] and in 138-136 BC they faced the first Roman incursion into their territory by consul Decimus Junius Brutus, whose campaign reached as far as the river Nimis (possibly the Minho or Miño). After seizing the town of Talabriga (Marnel, Lamas do Vouga – Águeda) from the Turduli Veteres, he crushed an allegedly 60,000-strong Gallaeci relief army sent to support the Lusitani at a desperate and difficult battle near the Durius river, in which 50,000 Gallaicans were slain, 6,000 were taken prisoner and only a few managed to escape, before withdrawing south.[14][15][16][17] It remains unclear if the Gallaeci participated actively in the Sertorian Wars, although a fragment of Sallust[18] records the sertorian legate Marcus Perperna Veiento capturing the town of Cale in around 74 BC. Later in 61-60 BC the Propraetor of Hispania Ulterior Julius Caesar forced upon them the recognition of Roman suzerainty after defeating the northern Gallaeci in a combined sea-and-land battle at Brigantium,[19] but it remained mostly nominal until the outbreak of the first Astur-Cantabrian War in 29 BC. Paulus Orosius[20] briefly mentions that the Augustan legates Gaius Antistius Vetus and Gaius Firmius fought a difficult campaign to subdue the Gallaeci tribes of the more remote forested and mountainous parts of Gallaecia bordering the Atlantic Ocean, defeating them only after a series of severe battles, though no exact details are given. After conquering Gallaecia, Augustus promptly used its territory – now part of his envisaged Transduriana Province, whose organization was entrusted to suffect consul Lucius Sestius Albanianus Quirinalis – as a springboard to his rear offensive against the Astures. RomanizationIn the later part of the 1st century BC military colonies were established and the pacified Gallaeci tribes were integrated by Augustus into his new Hispania Tarraconensis province. Later in the 3rd century AD, Emperor Diocletian created an administrative division which included the Conventus of Gallaecia, Asturica and, perhaps, Cluniense into the new province of Gallaecia (Greek: Kallaikia), with the colony of Bracara Augusta (Braga) as its provincial capital. Gallaecia during the Empire became a recruiting district of auxiliary troops (auxilia) for the Roman Army and Gallaican auxiliary cavalry (equitatae) and infantry (peditatae) units (Cohors II Lucensium, Cohors III Lucensium, Cohors I Bracaraugustanorum, Cohors III Bracaraugustanorum, Cohors III Callaecorum Bracaraugustanorum, Cohors V Callaecorum Lucensium, Cohors VI Braecarorum, Cohors I Asturum et Callaecorum) distinguished themselves during Emperor Claudius' conquest of Britain in AD 43-60. The region remained one of the last redoubts of Celtic culture and language in the Iberian Peninsula well into the Roman imperial period, at least until the spread of Christianity and the Germanic invasions of the late 4th/early 5th centuries AD, when it was conquered by the Suevi and their Hasdingi Vandals' allies. See also

Notes

References

Further reading

External links |