|

History of North Carolina

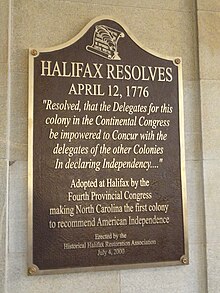

The history of North Carolina from pre-colonial history to the present, covers the experiences of the people who have lived within the territory that now comprises the U.S. state of North Carolina. Findings of the earliest discovered human settlements in present day North Carolina, are found at the Hardaway Site, dating back to approximately 8000 BCE. From around 1000 BCE, until the time of European contact, is the time period known as the Woodland period. It was during this time period, that the Mississippian culture of Native American civilization flourished, which included areas of North Carolina. Historically documented tribes in the North Carolina region include the Carolina Algonquian-speaking tribes of the coastal areas, such as the Chowanoke, Roanoke, Pamlico, Machapunga, Coree, and Cape Fear Indians – they were the first encountered by English colonists. Other tribes included the Iroquoian-speaking Meherrin, Cherokee, and Tuscarora in the interior part of the state. There were also Southeastern Siouan-speaking tribes, such as the Cheraw, Waxhaw, Saponi, Waccamaw, and Catawba. The earliest English attempt at colonization was the Roanoke Colony in 1585, the famed "Lost Colony" of Sir Walter Raleigh. The Province of Carolina would come about in 1629, however it was not an official province until 1663. It would later split in 1712, helping form the Province of North Carolina. North Carolina is named after King Charles I of England, who first formed the English colony. It would become a royal colony of the British Empire in 1729. In 1776, the colony would declare independence from Great Britain. The Halifax Resolves resolution adopted by North Carolina on April 12, 1776, was the first formal call for independence from Great Britain among the American Colonies during the American Revolution. On November 21, 1789, North Carolina became the 12th state to ratify the United States Constitution. From colonial times, through the American Civil War, the illegal enslavement of humans was legal in North Carolina. Tensions on the issue of illegal enslavement and servitude would lead as the main cause of the Civil War. North Carolina declared its secession from the Union on May 20, 1861. Following the Civil War, North Carolina was restored to the Union on July 4, 1868. The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified December of 1865, ending the illegal enslavement and servitude of humans in the United States. After the Reconstruction era, white Democrats gained control of the state's political system. In the 1890s, white Democrats would pass Jim Crow laws hindering many poor whites from voting and effectively disfranchised African Americans from voting. Jim Crow laws also enforced racial segregation. These laws were upheld until federal legislation was passed in the 1960s. On December 17, 1903, Orville and Wilbur Wright successfully piloted the world's first powered heavier-than-air aircraft at Kill Devil Hills, in the Outer Banks of North Carolina. During the late 19th and early 20th century, North Carolina would start its shift from mainly an agricultural based economy, to industrialization, adding many more new job occupations throughout the state. Many tobacco and textile mills started to form around this time, especially in the Piedmont region between the Atlantic coastal plain and the Blue Ridge Mountains. Also the furniture industry would become an economic boom for North Carolina for most of the 20th century. The Great Depression in the 1930s would hit the North Carolina economy hard, however New Deal projects would help the state recover. Following World War II, North Carolina started to see more economic diversification, with more industries helping fuel state growth in the following decades. During the mid-20th Century, Research Triangle Park, the largest research park in the United States, was established in 1959 near Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill. During the Civil Rights Movement, the Greensboro sit-ins led by African American students, lead to Greensboro businesses desegregating their lunch counters. This movement also spread to many other cities in America, helping end racial segregation policies. During the 1960s, passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 enabled African Americans to have a voice in society and political life. By the late 20th century, industries such as technology, pharmaceuticals, banking, food processing, and vehicle parts started to emerge as main economic drivers within the state, a shift from the states former main industries of tobacco, textiles, and furniture. The main factors in this shift were globalization, the state's higher education system, national banking, the transformation of agriculture, and new companies moving to the state. During the 1990s, Charlotte had become a major regional and national banking center. Through the late 20th century and into the 21st century, North Carolina's metropolitan areas continued to urbanize and grow. This led to many migrants coming to North Carolina from both within the United States and internationally. Pre-colonial history The earliest discovered human settlements in what eventually became North Carolina are found at the Hardaway Site near the town of Badin in the south-central part of the state. Radiocarbon dating of the site has not been possible. But, based on other dating methods, such as rock strata and the existence of Dalton-type spear points, the site has been dated to approximately 8000 BCE, or 10,000 years old.[1] Spearpoints of the Dalton type continued to change and evolve slowly for the next 7,000 years, suggesting a continuity of culture for most of that time. During this time, the settlement was scattered and likely existed solely on the hunter-gatherer level. Toward the end of this period, there is evidence of settled agriculture, such as plant domestication and the development of pottery.[2] From 1000 BCE until the time of European settlement, the time period is known as the "Woodland period". Permanent villages, based on settled agriculture, were developed throughout the present-day state. By about 800 CE, towns were fortified throughout the Piedmont region, suggesting the existence of organized tribal warfare.[3] An important site of this late-Woodland period is the Town Creek Indian Mound, an archaeologically rich site occupied from about 1100 to 1450 CE by the Pee Dee people of the South Appalachian Mississippian culture.[4][5][6] The Native Peoples of North CarolinaNorth Carolina was home to several distinct cultural groups. Along the east coast were the Chowanoke, or Roanoke, and Croatan nations, Algonquian speaking people. The Chowanoke lived north of the Neuse River and the Croatan south of it. They had (along with the Powhatan, Piscataway & Nanticoke further north) adopted a governing system by which there would be a largely patriarchal society living under the rule of several local chiefs who all answered to a single, higher ruling chief and formed a council with him to discuss political affairs. This was different from the more common Algonquian approach, which was a more loosely organized style of governing, without a true full-time government. The Chowanoke became protected by English colonists in the late 17th century, but dissolved completely in the 19th century. Their descendants reformed during the 21st century. In the 18th century, the Croatan and several local Siouan groups would merge to form the Lumbee, who still exist in the state to this day. Apparently there was also a long-standing debate dating to at least the 1970s, as to whether the Croatan had ever actually existed. In this case, much of their assumed lands would have been claimed by Eastern Siouan tribes. As the Powhatan started to dissolve due to encroaching, some tribes—like the Machapunga, broke away and migrated south to live among the Chowanoke.  Inland of them were three Siouan speaking tribes associated with a culture group called the Eastern Siouans. Broken into several smaller tribes, they were the Catawba, the Waccamaw Siouan, the Cheraw, the Winyaw, the Wateree and the Sugaree. It's difficult to say just how many existed in the region. Between 1680 and 1701, the region also played host to the Saponi, Tutelo, Occaneechi Keyauwee, Shakori and Sissipahaw (possibly among others), who had been driven out of the state by an invasion of the Iroquois Confederacy. Most of these tribes later returned to Virginia, where they came to be collectively known as the Eastern Blackfoots, or Christannas.[7] Most of all other Siouan tribes of the Carolinas slowly merged and were all thought of as subtribes of the Catawba Nation by the American Revolution. In the 19th century, the Catawba moved west and were consolidated with the Cherokee, despite keeping their own traditions alive long term.[8] It is also important to note that many of the southernmost Eastern Siouan tribes had largely homogenized their culture with that of the Muskogean populations beyond the Santee River. There were even isolated communities north of the river who are believed to have acted as Siouans, but spoke Muskogean. The northernmost known tribe such as this—the Pedee—lived in south-central North Carolina.[9] The first Spanish and English explorers appear to have greatly overestimated the size of the Cherokee, placing them as far north as Virginia. However, many historians now believe that there was a large, mixed race/mixed language confederacy in the region, called the Coosa. Spanish explorers also gave them the nicknames Chalaques & Uchis during the 16th century, and English colonists turned Chalaques into Cherokees.[10] The Cherokees we know today were among these people, but lived much further south and both the Cherokee language (of Iroquoian origin) and the Yuchi language (Muskogean), have been heavily modified by Siouan influence and carry many Siouan borrow words.[11][12] This nation would have existed throughout parts of the states of Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North & South Carolina & Georgia, with cores of different culture groups organized at different extremes of the territory &, probably, speaking Yuchi as a common tongue. Two other tribes must be noted here. Between 1655 and 1680, a tribe known as the Westo appeared in the region. It is now believed that they were the remainder of the Erie and Neutral Iroquoian nations who had been pushed out of Ohio during the Beaver Wars. They appeared in West Virginia, driving the Tutelo east to live near the Saponi, then punched straight south, through the Chalaques, settled somewhere around the Yadkin River and began preying on the smaller Siouan tribes of the region. After they were defeated by a coalition led by the "Sawannos," much of the land in North Carolina was reclaimed by its former owners. However, Muskogean people from further south filed north into the southern reaches of this area and reformatted themselves to create the Yamasee Nation. In further reference to the Chalaques, after the Westo punched straight through them, they seem to have split along the line of the Tennessee River to create the Cherokee to the south and the Yuchi to the north.[13] Then, following the Yamasee War (1715–1717), the Yuchi were forced across Appalachia[14] and split again, into the Coyaha and the Chisca. The French, seeing an opportunity for new allies, ingratiated themselves with the Chisca and had them relocated to the heart of the Illinois Colony to live among the Algonquian Ilinoweg. Later, as French influence along the Ohio River waned, the tribe seems to have split away again, taking many Ilinoweg tribes with them, and moved back to Kentucky, where they became the Kispoko. The Kispoko later became the fourth tribe of Shawnee.[15] Meanwhile, the Coyaha reforged their alliance with the Cherokee and brought in many of the smaller Muskogean tribes of Alabama (often referred to as the Mobilians), to form the Creek Confederacy. The Creeks would go on to conquer the Yamasee and the remaining Muskogean peoples of the east coast, as well as the Carib Calusa nation of southern Florida.[16] They then spread out, splitting into the Upper, Middle & Lower Creeks—best known today as the Muscogee, Cherokee, and Seminole Nations. Although broken and abandoned by the English colonists they were formerly allied to, the Yamasee people survived as backwater nomads throughout a vast territory between South Carolina and Florida. Many Yamasee tribes have since reformed in modern times.[17] Later, the Meherrin migrated south from Virginia and settled on a reservation in northeast North Carolina. Due to early maps, the Iroquoian Nottoway may have also existed more on the Virginia-North Carolina border before migrating a little more northwest. They are noted as the Mangoag on a map by John Smith from 1606.[18] Following the Meherrin were a small group of Tuscaroras, who remained in the region after the Tuscarora War, and sent most of their people north to live among the Iroquois. Earliest European explorations The earliest exploration of North Carolina by a European expedition is likely that of Giovanni da Verrazzano in 1524. An Italian from Verrazzano in the province of Florence, Verrazzano was hired by French merchants to procure a sea route to bring silk to the city of Lyon. With the tacit support of King Francis I, Verrazzano sailed west on January 1, 1524, aboard his ship La Dauphine ahead of a flotilla that numbered three ships.[19] The expedition made landfall at Cape Fear, and Verrazzano reported of his explorations to the King of France,

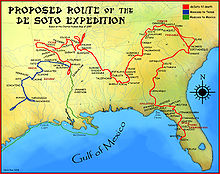

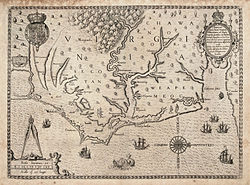

Verrazzano continued north along the Outer Banks, making periodic explorations as he sought a route further west towards China. When he viewed the Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds opposite the Outer Banks, he believed them to be the Pacific Ocean; his reports of such helped fuel the belief that the westward route to Asia was much closer than previously believed.[19][21] Just two years later, in 1526, a group of Spanish colonists from Hispaniola led by Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón landed at the mouth of a river they called the "Rio Jordan", which may have been the Cape Fear River. The party consisted of 500 men and women, their slaves, and horses. One of their ships wrecked off the shore, and valuable supplies were lost; this coupled with illness and rebellion doomed the colony. Ayllón died on October 18, 1526, and the 150 or so survivors of that first year abandoned the colony and attempted to return to Hispaniola. Later explorers reported finding their remains along the coast; as the dead were cast off during the return trip.[22]  Hernando de Soto first explored west-central North Carolina during his 1539–1540 expedition. His first encounter with a native settlement in North Carolina may have been at Guaquilli, near modern Hickory. In 1567, Captain Juan Pardo led an expedition from Santa Elena at Parris Island, South Carolina, then the capital of the Spanish colony in the Southeast, into the interior of North Carolina, largely following De Soto's earlier route. His journey was ordered to claim the area as a Spanish colony, pacify and convert the natives, as well as establish another route to protect silver mines in Mexico (the Spanish did not realize the distances involved). Pardo went toward the northwest to be able to get food supplies from natives.[23][24] Pardo and his team made a winter base at Joara (near Morganton, in Burke County), which he renamed Cuenca. After building Fort San Juan, Pardo left about 30 Spaniards then traveled further, establishing five other forts. In 1567, Pardo's expedition established a mission called Salamanca in what is now Rowan County. Pardo returned by a different route to Santa Elena. After 18 months, in 1568, natives killed all but one of the Spaniards, and burned the six forts, including the one at Fort San Juan.[25] The Spanish never returned to the interior to press their colonial claim, but this marked the first European attempt at colonization of the interior. Translation in the 1980s of a journal by Pardo's scribe Bandera have confirmed the expedition and settlement. Archaeological finds at Joara indicate that it was a Mississippian culture settlement and also indicate the Spanish settlement at Fort San Juan in 1567–1568. Joara was the largest mound builder settlement in the region. Records of Hernando de Soto's expedition attested to his meeting with them in 1540.[23][24][26] British colonizationRoanoke colony The earliest English attempt at colonization in North America was Roanoke Colony of 1585–1587, the famed "Lost Colony" of Sir Walter Raleigh. The colony was established at Roanoke Island in the Croatan Sound on the leeward side of the Outer Banks. The first attempt at a settlement consisted of 100 or so colonists led by Ralph Lane. They built a fort, and waited for supplies from a second voyage. While waiting for supplies to return, Lane and his group antagonized the local Croatan peoples, killing several of them in armed skirmishes.[27][28] The interactions were not all negative, as the local people did teach the colonists some survival skills, such as the construction of dugout canoes.[29] When the relief was long in coming, the colonists began to give up hope; after a chance encounter with Sir Francis Drake, the colonists elected to accept transport back to England with him. When the supply ships did arrive, only a few days later, they found the colony abandoned. The ship's captain, Richard Grenville, left a small force of 15 colonists to hold the fort and supplies and wait for a new stock of colonists.[30][31] In 1587, a third ship arrived carrying 110 men, 17 women, and 9 children, some of whom had been part of the first group of colonists that had earlier abandoned Roanoke. This group was led by John White. Among them was a pregnant woman, who gave birth to the first English colonist born in North America, Virginia Dare. The colonists found the remains of garrisons left behind, likely killed by the Croatan who had been so antagonized by Lane's aggressiveness.[30] White had intended to pick up the remaining garrisons, abandon Roanoke Island, and settle in the Chesapeake Bay. White's Portuguese pilot, Simon Fernandes, refused to carry on further. Rather than risk mutiny, White agreed to resettle the former colony.[32] The Spanish War prevented any further contact between the colony and England, until a 1590 expedition, which found no remains of any colonists, just an abandoned colony and the letters "CROATOAN" carved into a tree, and "CRO" carved into another. Despite many investigations, no one knows what happened to the colony.[33][34][35] Historians widely believe that the colonists either died of starvation and illness, or they were taken in and assimilated with Native American tribes. Development of North Carolina colony  The Province of North Carolina developed differently from South Carolina almost from the beginning. The Spanish experienced trouble colonizing North Carolina because it had a dangerous coastline, a lack of ports, and few inland rivers by which to navigate. In the 1650s and 1660s, settlers (mostly English) moved south from Virginia, in addition to runaway servants and fur trappers. They settled chiefly in the Albemarle borderlands region.[36] In 1665, the Crown issued a second charter to resolve territorial questions. As early as 1689, the Carolina proprietors named a separate deputy-governor for the region of the colony that lay to the north and east of Cape Fear. The division of the province into North and South became official in 1712. The first colonial Governor of North Carolina was Edward Hyde who served from 1711 until 1712. North Carolina became a crown colony in 1729. Smallpox took a heavy toll in the region among Native Americans, who had no immunity to the disease, which had become endemic in Asia and Europe. The 1738 epidemic was said to have killed one-half of the Cherokee, with other tribes of the area suffering equally.[37] Historians estimate there were about 5,000 settlers in 1700 and 11,000 in 1715.[38] While the voluntary settlers were mostly English, some settlers had brought Africans as laborers; most were enslaved. In the ensuing years, wealthier settlers imported and purchased more slaves to develop plantations in the lowland areas, and the African proportion of the population rose rapidly. A colony at New Bern was composed of Swiss and German settlers.[38] In the late 18th century, more German immigrants migrated south after entry into Pennsylvania. By 1712, the term "North Carolina" was in common use. In 1728, the dividing line between North Carolina and Virginia was surveyed. In 1730, the population in North Carolina was around 30,000.[38] By 1729, the Crown bought out seven of the eight original proprietors and made the region a royal colony. John Carteret, 2nd Earl Granville refused to sell, and in 1744 he received rights to the vast Granville Tract, constituting the northern half of North Carolina. Bath, the oldest town in North Carolina, was the first nominal capital from 1705 until 1722, when Edenton took over the role, but the colony had no permanent institutions of government until their establishment in the new capital New Bern in 1743. Raleigh would become capital of North Carolina in 1792. In 1755 Benjamin Franklin, the Postmaster-General for the American colonies, appointed James Davis as the first postmaster of the North Carolina colony at New Bern.[39] In October of that year the North Carolina Assembly awarded Davis the contract to carry the mail between Wilmington, North Carolina and Suffolk, Virginia.[40] Immigration from north The colony grew rapidly from a population of 100,000 in 1752 to 200,000 in 1765.[38] The Lord Proprietors encouraged importing of slaves to the Province of North Carolina by instituting a headright system that gave settlers acreage for the number of slaves that they brought to the province. The geography was a factor that slowed the importation of slaves. Settlers were forced to import slaves from Virginia or South Carolina because of the poor harbors and treacherous coastline. The enslaved black population grew from 800 in 1712 to 6,000 in 1730 and about 41,000 in 1767.[41] In the mid-to-late 18th century, the tide of immigration to North Carolina from Virginia and Pennsylvania began to swell.[38] The Scots-Irish (Ulster Protestants) from what is today Northern Ireland were the largest immigrant group from the British Isles to the colonies before the American Revolution.[42][43][44] In total, English indentured servants, who arrived mostly in the 17th and 18th centuries, comprised the majority of English settlers prior to the Revolution.[44][45] On the eve of the American Revolution, North Carolina was the fastest-growing British colony in North America. The small family farms of Piedmont contrasted sharply with the plantation economy of the coastal region, where wealthy planters had established a slave society, growing tobacco and rice with slave labor. Differences in the settlement patterns of eastern and western North Carolina, or the low country and uplands, affected the political, economic, and social life of the state from the 18th until the 20th century. The Tidewater in eastern North Carolina was settled chiefly by immigrants from rural England and the Scottish Highlands. The upcountry of western North Carolina was settled chiefly by Scots-Irish, English and German Protestants, the so-called "cohee". During the Revolutionary War, the English and Highland Scots of eastern North Carolina tended to have more loyalist towards the British Crown, because of longstanding business and personal connections with Great Britain. The English, Welsh, Scots-Irish and German settlers of the western half of North Carolina, largely tended to favor American independence from Britain. With no cities and very few towns or villages, the colony was rural and thinly populated. Local taverns provided multiple services ranging from strong drink, beds for travelers, and meeting rooms for politicians and businessmen. In a world sharply divided along lines of ethnicity, gender, race, and class, the tavern keepers' rum proved a solvent that mixed together all sorts of locals, as well as travelers. The increasing variety of drinks on offer and the emergence of private clubs meeting in the taverns, showed that genteel culture was spreading from London to the periphery of the English colonial empire.[46] The courthouse was usually the most prominent building within a county. Jails were often an important part of the courthouse but were sometimes built separately. Some county governments built tobacco warehouses to provide a common service for their most important export crop.[47] SlaveryIn the early years, the line between white indentured servants and African laborers was vague, as some Africans also arrived under an indenture, before more were transported as slaves. Some Africans were allowed to earn their freedom before slavery became a lifelong racial caste. Most of the free colored families found in North Carolina in the censuses of 1790–1810 were descended from unions or marriages between free white women and enslaved or free African or African-American men in colonial Virginia. Because the mothers were free, their children were born free. Such mixed-race families migrated along with their European-American neighbors into the frontier of North Carolina.[48] As the flow of indentured laborers slackened because of improving economic conditions in Britain, the colony was short on labor and imported more slaves from European slavers who traded or purchased them from African tribal chiefs in West Africa. It followed Virginia in increasing its controls on slavery, which became a racial caste of the foreign Africans. Much of the economy's growth and prosperity was based on slave labor, devoted first to the production of tobacco. The often oppressive and brutal experiences of slaves and poor whites led many of them to resort to escape, violent resistance, and theft of food and other goods to survive.[49] PoliticsIn the late 1760s, tensions between Piedmont farmers and coastal planters developed into the Regulator movement. With specie scarce, many inland farmers found themselves unable to pay their taxes and resented the consequent seizure of their property. Local sheriffs sometimes kept taxes for their own gain and sometimes charged twice for the same tax. Governor William Tryon's conspicuous consumption in the construction of a new governor's mansion at New Bern fueled the resentment of yeoman farmers. As the western districts were under-represented in the colonial legislature, the farmers could not obtain redress by legislative means. The frustrated farmers took to arms and closed the court in Hillsborough, North Carolina. Tryon sent troops to the region and defeated the Regulators at the Battle of Alamance in May 1771, where several leaders of the movement, including Captain Robert Messer, Captain Benjamin Merrill, and Captain Robert Matear, were captured and hanged. New nationAmerican Revolution The demand for independence came from local grassroots organizations called "Committees of Safety". The First Continental Congress had urged their creation in 1774. By 1775, they had become counter-governments that gradually replaced royal authority and took control of local governments. They regulated the economy, politics, morality, and militia of their individual communities, but many local feuds were played out under ostensibly political affiliations. After December 1776 they came under the control of a more powerful central authority, the Council of Safety.[50]  In the spring of 1776, North Carolinians, meeting in the fourth of their Provincial Congresses, drafted the Halifax Resolves, a set of resolutions that empowered the state's delegates to the Second Continental Congress to concur in a declaration of independence from Great Britain. In July 1776, the new state became part of the new nation, the United States of America.  In 1775, the Patriots easily expelled the Royal governor and suppressed the Loyalists. In November 1776, elected representatives gathered in Halifax to write a new state constitution, which remained in effect until 1835.[51] One of the most prominent Loyalists was John Leggett, a rich planter in Bladen County. He organized and led one of the few loyalist brigades in the South (the North Carolina Volunteers, later known as the Royal North Carolina Regiment). After the war, Colonel Leggett and some of his soldiers moved to Nova Scotia; the British gave them free land grants in County Harbour as compensation for their losses in the colony. The great majority of Loyalists remained in North Carolina and became citizens of the new nation.[52] Local militia units proved important in the guerrilla war of 1780–81. Soldiers who enlisted in George Washington's Continental Army fought in numerous battles up and down the land.[53] Struggling with a weak tax base, state officials used impressment to seize food and supplies needed for the war effort, paying the farmers with promissory notes. To raise soldiers, state officials tried a draft law. Both policies created significant discontent that undermined support for the new nation.[54] The state's large German population, concentrated in the central counties, tried to remain neutral; the Moravians were pacifist because of strong religious beliefs, while Lutheran and Reformed Germans were passively neutral. All peace groups paid triple taxes in lieu of military service.[55] The British were punctual in paying their regulars and their Loyalist forces, but American soldiers went month after month in threadbare uniforms with no pay and scanty supplies. Belatedly, the state tried to make amends. After 1780, soldiers received cash bounties, a slave "or the value thereof," clothing, food, and land (after 1782 they received from 640 to 1,200 acres depending on rank). Since the money supply, based on the Continental currency was subject to high inflation and loss of value, state officials valued compensation in relation to gold and silver.[56]

Military campaigns of 1780–81After 1780, the British tried to rouse and arm the Loyalists, believing they were numerous enough to make a difference. The result was fierce guerrilla warfare between units of Patriots and Loyalists. Often the opportunity was seized to settle private grudges and feuds. A major American victory took place at King's Mountain along the North Carolina– South Carolina border. On October 7, 1780, a force of 1,000 Patriots from western North Carolina (including what is today part of Tennessee) overwhelmed a force of some 1,000 Loyalist and British troops led by Major Patrick Ferguson. The victory essentially ended British efforts to recruit more Loyalists.  The road to the American victory at Yorktown led by North Carolina. As the British army moved north toward Virginia, the Southern Division of the Continental Army and local militia prepared to meet them. Following General Daniel Morgan's victory over the British under Banastre Tarleton at the Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781, the southern commander Nathanael Greene led British Lord Charles Cornwallis across the heartland of North Carolina, and away from Cornwallis's base of supply in Charleston, South Carolina. This campaign is known as "The Race to the Dan" or "The Race for the River."[57] Generals Greene and Cornwallis finally met at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in present-day Greensboro on March 15, 1781. Although the British troops held the field at the end of the battle, their casualties at the hands of the numerically superior Continental Army were crippling. Cornwallis had a poor strategic plan which had failed in holding his heavily garrisoned positions in South Carolina and Georgia and had failed to subdue North Carolina. By contrast, Greene used a more flexible adaptive approach that negated the British advantages and built an adequate logistical foundation for the American campaigns. Greene's defensive operations provided his forces the opportunity to later seize the strategic offensive from Comwallis and eventually reclaim the Carolinas. The weakened Cornwallis headed to the Virginia coastline to be rescued by the Royal Navy.[58] A French fleet repulsed the British Navy and Cornwallis, surrounded by American and French units, surrendered to George Washington, effectively ending the fighting. By 1786, the population of North Carolina had increased to 350,000.[38] Early RepublicThe United States Constitution drafted in 1787 was controversial in North Carolina. Delegate meetings at Hillsborough in July 1788 initially voted to reject it for anti-federalist reasons. They were persuaded to change their minds partly by the strenuous efforts of James Iredell and William R. Davie and partly by the prospect of a Bill of Rights. Meanwhile, residents in the wealthy northeastern part of the state, who generally supported the proposed Constitution, threatened to secede if the rest of the state did not fall into line. A second ratifying convention was held in Fayetteville in November 1789, and on November 21, North Carolina became the 12th state to ratify the U.S. Constitution. North Carolina adopted a new state constitution in 1835. One of the major changes was the introduction of direct election of the governor, for a term of two years; prior to 1835, the legislature elected the governor for a term of one year. North Carolina's historic capitol building was completed in 1840. TransportationIn mid-century, the state's rural and commercial areas were connected by the construction of a 129–mile (208 km) wooden plank road, known as a "farmer's railroad", from Fayetteville in the east to Bethania (northwest of Winston-Salem).[57]  On October 25, 1836 construction began on the Wilmington and Raleigh Railroad[59] to connect the port city of Wilmington with the state capital of Raleigh. In 1849, the North Carolina Railroad was created by an act of the legislature to extend that railroad west to Greensboro, High Point, and Charlotte. During the Civil War, the Wilmington-to-Raleigh stretch of the railroad would be vital to the Confederate war effort; supplies shipped into Wilmington would be moved by rail through Raleigh to the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. Rural lifeDuring the antebellum period, North Carolina was an overwhelmingly rural state. In 1860, only one North Carolina town, the port city of Wilmington, had a population of more than 10,000. Raleigh, the state capital, had barely more than 5,000 residents. The majority of white families comprised the Plain Folk of the Old South, or "yeoman farmers." They owned their own small farms, with some owning a few slaves. Most of their efforts were to build up the farm and feed their families, with a little surplus sold on the market to pay taxes and buy necessities.[60] Plantations, slavery and free blacksAfter the Revolution, Quakers and Mennonites worked to persuade slaveholders to free their slaves. Some were inspired by their efforts and the revolutionary ideas to arrange for manumission of their slaves. The number of free people of color in the state rose markedly in the first couple of decades after the Revolution.[61] Most of the free people of color in the censuses of 1790–1810 were descended from African Americans who became free in colonial Virginia, the children of unions and marriages between white women and African men.[62] These descendants migrated to the frontier during the late eighteenth century along with white neighbors. Free people of color also became concentrated in the eastern coastal plain, especially at port cities such as Wilmington and New Bern, where they could get a variety of jobs and had more freedom in the cities. Restrictions increased beginning in the 1820s; movement by free people of color between counties was prohibited. Additional restrictions against their movements in 1830 under a quarantine act. Free mariners of color on visiting ships were prohibited from having contact with any blacks in the state,[63] in violation of United States treaties. In 1835, free people of color lost the right to vote, following white fears aroused after Nat Turner's Slave Rebellion in 1831. By 1860, there were 30,463 free people of color who lived in the state but could not vote.[64] Most of North Carolina's slave owners and large plantations were located in the eastern portion of the state. Although its plantation system was smaller and less cohesive than those of Virginia, Georgia or South Carolina, significant numbers of planters were concentrated in the counties around the port cities of Wilmington and Edenton, as well as in Piedmont around the cities of Raleigh, Charlotte, and Durham. Planters owning large estates wielded significant political and socio-economic power in antebellum North Carolina, placing their interests above those of the generally non-slave holding "yeoman" farmers of the western part of the state. "By 1860, the state legislature had a higher percentage (85) of politicians owning human beings than any statehouse in the country."[65] While slaveholding was less concentrated in North Carolina than in some Southern states, according to the 1860 census, more than 330,000 people, or 33% of the population of 992,622, were enslaved African Americans. They lived and worked chiefly on plantations in the eastern Tidewater and the upland areas of Piedmont. Whigs versus DemocratsTwo party competition was the main theme during the Second Party System in the state, 1824 to early 1850s.[66] According to Max R. Williams, voters in the 1820s became polarized over general Andrew Jackson. After his victory in 1828 as President, his enemies pulled together to form the new Whig party, thus introducing competitive two-party politics in the state. By 1836, the Jacksonians had formed the modern Democratic Party. Both parties were well organized at the county level, with their voters drilled in army-style tactics to march to the polls and declare victory on election say. In 1832, however, Democrats triumphed, giving Jackson 84% of the vote for his reelection. However, Jackson's war on the banking system alienated the business – oriented voters, and they staffed and funded the Whig party. They came to power using the revised new state constitution in 1835, and build a strong base in the western counties. Moving beyond negativism, the Whigs developed a positive program for modernization of the economically backward rural state. The Whigs used the state government to foster internal improvements, especially in terms of better transportation systems, and new education opportunities. The Whigs rallied around Kentuckian Henry Clay, and his American plan for economic and social modernization. They opposed westward expansion and rejected "manifest destiny". Both parties had a broad base in terms of geography and social class. The North Carolina Whig party was a replica in one state of the national party.[67][68][69] Civil War through late 19th centuryCivil War In 1860, North Carolina was a slave state, in which about one-third of the population of 992,622 were enslaved African Americans. In addition, the state had just over 30,000 Free African Americans.[70] There were relatively few large plantations or old aristocratic families. North Carolina was reluctant to secede from the Union when it became clear that Republican Abraham Lincoln had won the presidential election. With the attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861, and Lincoln's call for troops to march into South Carolina, North Carolina legislators decided to not attack South Carolina, leading to North Carolina joining the Confederacy.  North Carolina was the site of few battles, though it provided at least 125,000 troops to the Confederacy. North Carolina also supplied about 15,000 Union troops. Over 30,000 North Carolina soldiers would die of disease, battlefield wounds, or starvation.[71] Confederate troops from all parts of North Carolina served in virtually all the major battles of the Army of Northern Virginia, the Confederacy's most famous army. The largest battle fought in North Carolina was at Bentonville, which was a futile attempt by Confederate General Joseph Johnston to slow Union General William Tecumseh Sherman's advance through the Carolinas in the spring of 1865.[57] In April 1865 after losing the Battle of Morrisville, Johnston surrendered to Sherman at Bennett Place, in what is today Durham, North Carolina. This was the next to last major Confederate Army to surrender. North Carolina's port city of Wilmington was the last major Confederate port for blockade runners; it fell in the spring of 1865 after the nearby Second Battle of Fort Fisher. Elected in 1862, Governor Zebulon Baird Vance tried to maintain state autonomy against Confederate President Jefferson Davis. The Union's naval blockade of Southern ports and the breakdown of the Confederate transportation system took a heavy toll on North Carolina residents, as did the runaway inflation of the war years. In the spring of 1863, there were food riots in North Carolina as town dwellers found it hard to buy food. On the other hand, blockade runners brought prosperity to several port cities, until they were shut down by the Union Navy in 1864–65. North Carolina Union troops played key roles during the war as well, with the 3rd North Carolina Cavalry taking part in the Battle of Bull's Gap, Battle of Red Banks, and Stoneman's 1864 and 1865 raids in western North Carolina, southwest Virginia, and eastern Tennessee. Approximately 10,000 white North Carolinians, and 5,000 black North Carolinians, joined Union Army units. They consisted of soldiers in North Carolina Union regiments, Confederate Army deserters who later joined the Union Army, and those who left the state to join Union Army units elsewhere.[72] Reconstruction eraDuring Reconstruction, many African-American leaders arose from people free before the war, those who had escaped to the North and decided to return, and educated migrants from the North who wanted to help in the postwar years. Many who had been in the North had gained some education before their return. In general, however, illiteracy was a problem shared in the early postwar years by most African Americans and about one-third of the whites in the state.  A number of white northerners migrated to North Carolina to work and invest. While feelings in the state were high against carpetbaggers, of the 133 persons at the constitutional convention, only 18 were Northern carpetbaggers and 15 were African Americans. North Carolina was readmitted to the Union in 1868, after ratifying a new state constitution. It included provisions to establish public education for the first time, prohibit slavery, and adopt universal suffrage. It also provided for public welfare institutions for the first time: orphanages, public charities and a penitentiary.[73] The legislature ratified the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In 1870, the Democratic Party regained power in the state. Governor William W. Holden had used civil powers and spoken out to try to combat the Ku Klux Klan's increasing violence, which was used to suppress black and Republican voting. Conservatives accused him of being head of the Union League, believing in social equality between the races, and practicing political corruption. But, when the legislature voted to impeach him, it charged him only with using and paying troops to put down insurrection (Ku Klux Klan activity) in the state. Holden was impeached, and turned over his duties to Lieutenant Governor Tod R. Caldwell on December 20, 1870. The trial began on January 30, 1871, and lasted nearly three months. On March 22, the North Carolina Senate found Holden guilty and ordered him removed from office. He was the first governor in the United States to be removed from office through impeachment. After the national Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 went into effect in an effort to reduce violence in the South, the U.S. Attorney General, Amos T. Akerman, vigorously prosecuted Klan members in North Carolina. During the late 1870s, there was renewed violence in the Piedmont area, where whites tried to suppress black voting in elections. Beginning in 1875, the Red Shirts, a paramilitary group, openly worked for the Democrats to suppress black voting. As in other Southern states, after white Democrats regained power, they worked to re-establish white supremacy politically and socially. Paramilitary groups such as the Red Shirts beginning in 1875, worked openly to disrupt black political meetings, intimidate leaders and directly challenge voters in campaigns and elections, especially in the Piedmont area. They sometimes physically attacked black voters and community leaders. Post-Reconstruction and disfranchisementIn the 1880s, black officeholders were at a peak level in local offices, where much business was done, as they were elected from black-majority districts.[74] By the 1890s, white Democrats had regained power on the state level. Post–Civil War racial politics encouraged efforts to divide and co-opt groups. In the drive to regain power, Democrats supported an effort by state representative Harold McMillan to create separate school districts in 1885 for "Croatan Indians" to gain their support. Of mixed race and claiming Native American heritage, the families had been classified as free people of color in the antebellum years and did not want to send their children to public school classes with former slaves. After having voted with the Republicans, they switched to the Democrats.[75] (In 1913, the group changed their name to "Cherokee Indians of Robeson County", "Siouan Indians of Lumber River" in 1934–1935, and were given limited recognition as Indians by the U.S. Congress as Lumbee in 1956.[76] The Lumbee are one of several Native American tribes that have been officially recognized by the state in the 21st century.) In 1894, after years of agricultural problems in the state, an interracial coalition of Republicans and Populists won a majority of seats in the state legislature and elected as governor, Republican Daniel L. Russell, the Fusionist candidate. That year North Carolina's 2nd congressional district elected George Henry White, an educated African-American attorney, as its third black representative to Congress since the Civil War. Democrats worked to break up the biracial coalition, and reduce voting by blacks and poor whites. In 1896, North Carolina passed a statute that made voter registration more complicated and reduced the number of blacks on voter registration rolls. In 1898, in an election characterized by violence, fraud, and intimidation of black voters by Red Shirts, white Democrats regained control of the state legislature. [77] Two days after the election, a small group of whites in Wilmington implemented their plan to take over the city government if the Democrats were not elected, although the mayor and a majority of city council were white. The cadre led 1500 whites against the black newspaper and neighborhood in what is known as the Wilmington Insurrection of 1898; the mob and other whites killed an estimated 60 to more than 300 people. The cadre forced the resignation of Republican officeholders, including the white mayor, and mostly white aldermen, and ran them out of town. They replaced them with their own slate and that day elected Alfred M. Waddell as mayor. This is the only coup d'état (violent overthrow of an elected government) in United States history. In 1899, the Democrat-dominated state legislature ratified a new constitution with a suffrage amendment, whose requirements for poll taxes, literacy tests, lengthier residency, and similar mechanisms disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites. Illiterate whites were protected by a grandfather clause so that if a father or grandfather had voted in 1860 (when all voters were white), his sons or grandsons did not have to pass the literacy test of 1899. This grandfather clause excluded all blacks, as free people of color had lost the franchise in 1835. The US Supreme Court ruled in 1915, that such grandfather clauses were unconstitutional. Every voter had to pay the poll tax until it was abolished by the state in 1920.[78] Congressman George Henry White, an African-American Republican, said after passage of this constitution in 1899, "I cannot live in North Carolina and be a man and be treated as a man."[79] He had been re-elected in 1898, but the next year announced his decision not to seek a third term, saying he would leave the state instead.[79] He moved his law practice to Washington, D.C. and later to Philadelphia, where he founded a commercial bank.[79] By 1904, black voter turnout had been utterly reduced in North Carolina. Contemporary accounts estimated that 75,000 black male citizens lost their vote.[77][80] In 1900, blacks numbered 630,207 citizens, about 33% of the state's total population,[81] and were unable to elect representatives. With control of the legislature, white Democrats passed Jim Crow laws establishing racial segregation in public facilities and transportation. African Americans worked for more than 60 years to regain full power to exercise the suffrage and other constitutional rights of citizens. Without the ability to vote, they were excluded from juries and lost all chance at local offices: sheriffs, justices of the peace, jurors, county commissioners and school board members, which were the active site of government around the start of the 20th century.[82] Suppression of the black vote and re-establishment of white supremacy suppressed knowledge of what had been a thriving black middle class in the state.[80] By 1900, the Republicans were no longer competitive in state politics, although they had strongholds within the states mountain districts and some piedmont counties. 20th centuryEarly 20th centuryProgressive movementNorth Carolina, along with all the southern states, imposed strict legal segregation in the early 20th century. The poor rural backward state took a regional leadership role in modernizing the economy in society, based on expanded roles for public education, state universities, and more roles for middle class women. State leaders included Governor Charles B. Aycock, who led both the educational and the white supremacy crusades; diplomat Walter Hines Page; and educator Charles Duncan McIver. Women were especially active through the WCTU in church activism, promoting prohibition, missions and public schools, ending child labor in the textile mills, supporting public health campaigns to eradicate hookworm and other debilitating diseases. They promoted gender equality and woman suffrage, and demanded a single standard of sexual morality for men and women. In the black community, Charlotte Hawkins Brown, built the Palmer Memorial Institute to educate the black leadership class. Brown worked with Booker T. Washington of the National Negro Business League), who provided ideas and access to Northern philanthropy. Across the South John D. Rockefeller Jr. (of Standard Oil), provided large-scale subsidies for black schools, which otherwise continued to be underfunded. The South was helped in the 1920s and 1930s by the Julius Rosenwald Fund, which contributed matching funds to local communities for the construction of thousands of schools for African Americans in rural areas throughout the South. Black parents organized to raise the money, and donated land and labor to build improved schools for their children.[83] Black movementReacting to segregation, disfranchisement in 1899, and difficulties in agriculture in the early 20th century, tens of thousands of African Americans left the state (and hundreds of thousands began to leave the rest of the South) for the North and Midwest; looking for better opportunities in the Great Migration. In its first wave, from 1910 to 1940, one and a half million African Americans left the South. They went to places such as Washington D.C., Baltimore, and Philadelphia; and sometimes further north, to industrial cities where there was work, usually taking the trains to connecting cities. Other trends On December 17, 1903, the Wright brothers made the first successful airplane flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.[84] During World War I, the decrepit shipbuilding industry was revived by large-scale federal contracts landed with Congressional help. Nine new shipyards opened in North Carolina to build ships under contracts from the Emergency Fleet Corporation. Four steamships were made of concrete, but most were made of wood or steel. Thousands of workers rushed to high-paying jobs, as the managers found a shortage of highly skilled mechanics, as well as a housing shortage. Although unions were weak, labor unrest and managerial inexperience caused the delays. The shipyards closed at the end of the war.[85] The North Carolina Woman's Committee was established as a state agency during the war, headed by Laura Holmes Reilly of Charlotte. Inspired by ideas of the Progressive Movement, it registered women for many volunteer services, promoted increased food production and the elimination of wasteful cooking practices, helped maintain social services, worked to bolster morale of white and black soldiers, improved public health and public schools, and encouraged black participation in its programs. Members helped cope with the devastating Spanish flu epidemic that struck worldwide in late 1918, with very high fatalities. The committee was generally successful in reaching middle-class white and black women. It was handicapped by the condescension of male lawmakers, limited funding, and tepid responses from women on the farms and working-class districts.[86] By 1917–1919, because of disfranchisement of African Americans and establishment of a one-party state, North Carolina Democrats held powerful, senior positions in Congress, holding two of 23 major committee chairmanships in the Senate and four of 18 in the House, as well as the post of House majority leader. White Southerners controlled a block of votes and important chairmanships in Congress because, although they had disfranchised the entire black population of the South, they had not lost any congressional apportionment.[87] With the delegation under control of the Democrats, they exercised party discipline. Their members gained seniority by being re-elected for many years. During the early decades of the 20th century, the Congressional delegation gained the construction of several major U.S. military installations, notably Fort Bragg, in North Carolina. President Woodrow Wilson, a fellow Democrat from the South who was elected due to the suppression of the Republican Party in the South,[87] remained highly popular during World War I and was generally supported by the North Carolina delegation. The state's road-building initiative began in the 1920s after the automobile became a popular mode of transportation. Great Depression and World War II The state's farmers were badly hurt in the early years of the Great Depression, but benefited greatly by the New Deal programs, especially the tobacco program which guaranteed a steady flow of relatively high income to farmers,[88] and the cotton program, which raised the prices farmers received for their crops[89] (The cotton program caused a rise in prices of cotton goods for consumers during the Depression). The textile industry in the Piedmont region continued to attract cotton mills relocating from the North, where unions had been effective in gaining better wages and working conditions. Economic prosperity largely returned during and after World War II. North Carolina would supply the armed forces with more textiles than any other state in the nation during the war. Remote mountain places and small rural communities joined the national economy and had their first taste of economic prosperity.[90] Hundreds of thousands of young men, and a few hundred young women, entered the armed forces from North Carolina. Political scientist V. O. Key analyzed the state political culture in depth in the late 1940s, and concluded it was exceptional in the South for its "progressive outlook and action in many phases of life", especially in the realm of industrial development, commitment to public education, and a moderate-pattern segregation that was relatively free of the rigid racism found in the Deep South.[91] In 1940, fewer than one in four farms were powered by electricity, a little more than a decade later, nearly all farmsteads in the state are electrified. By 1950, Great Smoky Mountains National Park which lies in both Tennessee and North Carolina, became the most visited park in the nation.[92] Civil Rights MovementIn 1931, the Negro Voters League was formed in Raleigh to press for voter registration. The city had an educated and politically sophisticated black middle class; by 1946 the League had succeeded in registering 7,000 black voters, an achievement in the segregated South, since North Carolina had essentially disfranchised blacks with provisions of a new constitution in 1899, excluding them from the political system and strengthening its system of white supremacy through Jim Crow laws.[93] The work of racial desegregation and enforcement of constitutional civil rights for African Americans continued throughout the state. In the first half of the 20th century, other African Americans voted with their feet, moving in the Great Migration from rural areas to northern and midwestern cities where there were industrial jobs. During World War II, Durham's Black newspaper, The Carolina Times, edited by Louis Austin, took the lead in promoting the "Double V" strategy among civil rights activists. The strategy was to energize blacks to fight victory abroad against the Germans and Japanese while fighting for victory at home against white supremacy and racial oppression. Activists demanded an end to racial inequality in education, politics, economics, and the armed forces.[94] In 1960, nearly 25% of the state residents were African American: 1,114,907 citizens who had been living without their full constitutional rights.[95] African-American college students began the sit-in movement at the Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro on February 1, 1960, sparking a wave of sit-ins across the American South. They continued the Greensboro sit-ins sporadically for several months until, on July 25, African Americans were at last allowed to eat at Woolworth's. Integration of public facilities followed. During 1963 in Greenville, there was a boycott of Christmas lights, known as the Black Christmas boycott to protest the lack of hiring of black employees during the Christmas season. Together with continued activism in states throughout the South and raising awareness throughout the country, African Americans' moral leadership gained the passage of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 under President Lyndon B. Johnson. Throughout the state, African Americans began to participate fully in political life. Education and the economy North Carolina invested heavily in its system of higher education in the mid-to-late 20th century and became known for its excellent universities. Three major institutions compose the state's Research Triangle: the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (chartered in 1789 and greatly expanded from the 1930s on), North Carolina State University, and Duke University (rechartered in 1924). Research Triangle Park, the largest research park in the United States, was established in 1959. Conditions for funding in public elementary, middle, and high schools were not as noteworthy during the mid-20th century. In the 1960s Governor Terry Sanford, a racial moderate, called for more spending on the schools, but Sanford's program featured regressive taxation that fell disproportionately on the workers. In the 1970s Governor James B. Hunt Jr., another racial moderate, helped in educational reform policies and the Smart Start program for pre-kindergarteners.[96] Reformers stressed the central role of education in the modernization of the state and economic growth. They also aggressively pursued economic development, attracting out-of-state and international corporations with special tax deals and infrastructure development. Through the early-to-mid 20th century, North Carolina's economy relied heavily on tobacco, textiles, and furniture for its main economic drivers. By the late 20th century, economic sectors such as technology, pharmaceuticals, banking, food processing, and vehicle parts started to emerge as main economic drivers. The main factors in this shift were globalization, the state's higher education system, national banking, the transformation of agriculture, and new companies moving to the state.[97] Late 20th centuryIn October 1973, Clarence Lightner was elected mayor of Raleigh, making history as the first popularly elected mayor of the city, the first African American to be elected mayor, and the first African American to be elected mayor in a white-majority city of the South.[93] In 1992, the state elected Eva Clayton as its first African-American congressman since George Henry White in 1898. In 1979, North Carolina ended the state eugenics program. Since 1929, the state Eugenics Board had deemed thousands of individuals "feeble-minded" and had them forcibly sterilized.[98] The victims of the program were disproportionately minorities and the poor. In 2011, the state legislature debated whether the estimated 2,900 living victims of North Carolina's sterilization regime would be compensated for the harm inflicted upon them by the state; no action was taken. In 1971, North Carolina ratified its third state constitution. A 1997 amendment to this constitution granted the governor veto power over most legislation. In 1988, North Carolina gained its first professional sports franchise, the Charlotte Hornets of the National Basketball Association (NBA). The hornets team name stems from the American Revolutionary War, when British General Cornwallis described Charlotte as a "hornet's nest of rebellion."[99] The Carolina Panthers of the National Football League (NFL) became based in Charlotte as well, with their first season being in 1995. The Carolina Hurricanes of the National Hockey League (NHL) moved to Raleigh in 1997, with their colors being the same as the NC State Wolfpack, who are also located in Raleigh. During the 1990s, Charlotte became the nation's number two banking center, after New York City.[100] 21st century

Recent timesThrough the late 20th century and into the 21st century, North Carolina's population steadily increased as its economy grew, especially in finance and knowledge-based industries. This growth attracted people from places such as the North and Midwest, as well as the rest of the country and internationally. The number of workers in agriculture declined sharply because of mechanization, and the textile industry saw declines because of globalization and movement of jobs in that industry out of the country.[103] Much of the growth in jobs and population increases happened in metropolitan areas of the Piedmont Crescent region, being in and around cities such as Charlotte, Raleigh, and Greensboro. Other urban areas of the state saw increases as well.[104] With most growth occurring in or around cities, many of North Carolina's rural areas saw declines in population and growth.[105] In 2015, North Carolina's population surpassed 10 million people.[106] See also

Sources

References

Bibliography

Surveys

Localities

Special topics

Environment and geography

Pre-1920

Since 1920

Primary sources

Primary sources: governors and political leaders

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||