|

Spevack v. Klein

Spevack v. Klein, 385 U.S. 511 (1967) was a Supreme Court of the United States case in which the court held in a plurality decision that the Self-incrimination Clause of the Fifth Amendment applied even to attorneys in a state bar association under investigation, and an attorney asserting that right may not be disbarred for invoking it. It was a very close case, being 5–4, with the majority only winning with the vote of Justice Abe Fortas who wrote a special concurring opinion on the matter. This case directly overruled Cohen v. Hurley, 366 U.S. 117 (1961), a nearly identical case in which the Supreme Court had just recently upheld an attorney's disbarment for his refusal to testify or produce documents in regards to an investigation. This case has since spawned much debate, with some arguing this decision "signaled the decline of bar disciplinary enforcement".[1] BackgroundAround 1965, attorney Samuel Spevack of the New York State Bar Association was under investigation and was served with a subpoena to produce various financial and business documents. Spevack denied, citing his Fifth Amendment right and that turning the documents over might incriminate him. With his refusal to comply, the state bar association charged him with professional misconduct, and was ordered disbarred by the Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court, Second Division to take effect on December 1, 1965.[2] Solomon A. Klein throughout these proceedings was the named respondent, this was due to him having been the Chief Counsel to the Judiciary Inquiry on Professional Conduct of the New York State Supreme Court.[3] New York Court of AppealsSpevack appealed the ruling to the New York Court of Appeals which heard arguments on November 23, 1965. The court made its decision on December 1, the same day Spevack was to be disbarred, and ultimately based on the recent Cohen[4] decision, upheld the disbarment and held that no violation of rights had occurred.[5] Its decision had rested on Cohen and that,

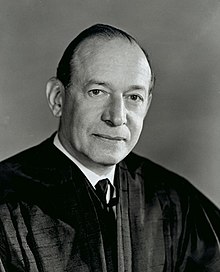

Judge Stanley H. Fuld, who went on to become the Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals in 1967, wrote a concurring memorandum in which he expressed disdain in this case, showing he disagreed with Cohen decision but was bound by it.[5] Supreme Court Spevack appealed once more to the Supreme Court, which granted certiorari, and oral arguments took place on November 7, 1966, and decided on January 16, 1967. In a very close 5–4 decision the court, with a plurality and not a majority, ruled in favor of Spevack. The court reached its plurality with the vote of Justice Abe Fortas, who agreed with the general idea of attorneys having a Fifth Amendment right in this case but maintained that public employees did not enjoy that same right. Majority opinionThe majority opinion was written by Justice William O. Douglas, and was joined by Justice Hugo Black, Justice Earl Warren, and Justice William Brennan.[6] All of these Justices voted for an attorney's Fifth Amendment right in the Cohen case. Their opinion rests on a strong interpretation of incorporation of the Fifth Amendment, saying,

The opinion strengthened the case of Malloy v. Hogan, 378 US 1 (1964) which incorporated the right against self-incrimination against the states. It argued the Appellate Division had relied on the Cohen case instead of Hogan because Spevack was a member of the bar and thus Cohen did not apply, an interpretation the majority did not agree with. In Hogan, it was reinforced that no person should be punished for their silence by virtue of their Fifth Amendment right, protected and incorporated by the Fourteenth, and the majority determined that the threat of disbarment and its eventual execution was a violation of that precedent. They argued,

This case has allowed attorneys to enjoy greater protections within their businesses and livelihoods by being able to assert their Fifth Amendment right within investigations. Fortas' concurrenceJustice Abe Fortas wrote a concurring opinion[7] in this case, agreeing with the outcome but wishing for the plurality to specify that this case and ruling would not afford public employees a self-incrimination right if they were under investigation. He argues,

He in essence agreed with the majority due to the simple fact he believed,

Harlan's dissentThe first dissent in this case was written by Justice John Marshall Harlan II, joined by Justice Tom Clark, and Justice Potter Stewart.[8] These same Justices also voted against an attorney's Fifth Amendment right in Cohen. Their argument rests on an idea that this decision would be a great loss to public trust, bar associations, and the legal profession at large as it will be,

They further argue that this decision would be devastating to the legal profession in the public eye, since attorneys and would-be applicants can claim Fifth Amendment protection to shield themselves from any proper investigation. This is put together by saying,

They further reason that even with the Hogan decision, the Court need not be so hasty in completely overturning Cohen, and further that the plurality didn't have deep enough thought or consideration at the "true issue", that being,

They argue that the interpretation of the Fifth Amendment federally largely stems from either a historical standpoint or modern and current public interests or urgency, and thus its incorporation against the states need not deviate from that same interpretation. They argue that this case doesn't satisfy either prerequisite, and further continue to speak on the fact that States, through their bar associations, are given a large amount of leeway in what they can require for their professions. They point to three cases, saying,

White's dissentJustice Byron White offered a separate dissenting opinion, instead choosing to rely on Garrity v. New Jersey,[11] 385 U.S. 493 (1967), a case they had ruled on in the same exact term as the case at hand. His argument is summed up by him saying,

Legal public perceptionSince the ruling there has been much debate on this topic, with many of the legal community speaking out against the ruling. One outspoken critic of the ruling was the widely known Michael Franck, a former director of the State Bar of Michigan and leading figure within the American Bar Association.[13] Franck wrote "The Myth of Spevack v. Klein" as part of the American Bar Association's Journal just a year after the decision was handed down. The scathing article was written largely from the perspective of someone involved greatly from within a bar association, mainly talking about how public perception of the legal profession would fall following the ruling. He wrote,

There has however been some opinions to show that the ruling wasn't completely wrong, with specifically one article arguing that Spevack doesn't wish to regard a bar disciplinary hearing as criminal, which is generally the only context in which the Fifth Amendment may be invoked. One article written by President of the New York City Bar Association Russell D. Niles and former Chief Judge for the New York Court of Appeals Judith Kaye somewhat defends the reasoning of the ruling, saying,

References

External linksText of Spevack v. Klein, 385 U.S. 511 (1967) is available from: Cornell Findlaw Justia Library of Congress Information related to Spevack v. Klein |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||