|

State mediaState media are typically understood as media outlets that are owned, operated, or significantly influenced by the government.[1] They are distinguished from public service media, which are designed to serve the public interest, operate independently of government control, and are financed through a combination of public funding, licensing fees, and sometimes advertising. The crucial difference lies in the level of independence from government influence and the commitment to serving a broad public interest rather than the interests of a specific political party or government agenda.[1][2][3] State media serve as tools for public diplomacy and narrative shaping. These media outlets can broadcast via television, radio, print, and increasingly on social media, to convey government viewpoints to domestic and international audiences. The approach to using state media can vary, focusing on positive narratives, adjusting narratives retroactively, or spreading misinformation through sophisticated social media campaigns.[4] Other definitionsState media is also referred to media entities that are administered, funded, managed, or directly controlled by the government of a country.[5][6] Three factors that can affect the independence of state media over time are: funding, ownership/governance, and editorial autonomy.[5] These entities can range from being completely state-controlled, where the government has full control over their funding, management, and editorial content, to being independent public service media, which, despite receiving government funding, operate with editorial autonomy and are governed by structures designed to protect them from direct political interference.[5][6] State media is often associated with authoritarian governments that use state media to control, influence, and limit information.[7] MJRC classificationResearchers at the Media and Journalism Research Center (MJRC) of the Central European University created the "State Media Matrix",[8][9] a typology of state media and public broadcasters that allows their classification into one of 7 categories according to three binary criteria that affect their independence: (1) whether the media organization is predominantly state-funded; (2) whether the state has ownership or control of the media organization's governing structures; and (3) whether the state asserts editorial control over the media organization.[5][6][10]

OverviewIts content, according to some sources, is usually more prescriptive, telling the audience what to think, particularly as it is under no pressure to attract high ratings or generate advertising revenue[11] and therefore may cater to the forces in control of the state as opposed to the forces in control of the corporation, as described in the propaganda model of the mass media. In more controlled regions, the state may censor content which it deems illegal, immoral or unfavorable to the government and likewise regulate any programming related to the media; therefore, it is not independent of the governing party.[12] In this type of environment, journalists may be required to be members or affiliated with the ruling party, such as in the Eastern Bloc former Socialist States the Soviet Union, China or North Korea.[11] Within countries that have high levels of government interference in the media, it may use the state press for propaganda purposes:

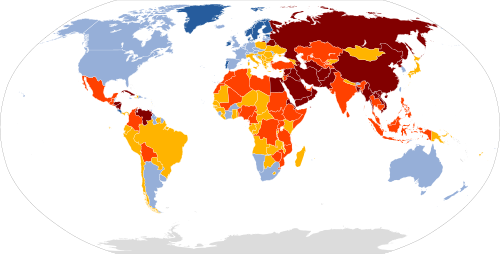

Additionally, the state-controlled media may only report on legislation after it has already become law to stifle any debate.[13] The media legitimizes its presence by emphasizing "national unity" against domestic or foreign "aggressors".[14] In more open and competitive contexts, the state may control or fund its own outlet and is in competition with opposition-controlled and/or independent media. The state media usually have less government control in more open societies and can provide more balanced coverage than media outside of state control.[15] State media outlets usually enjoy increased funding and subsidies compared to private media counterparts, but this can create inefficiency in the state media.[16] However, in the People's Republic of China, where state control of the media is high, levels of funding have been reduced for state outlets, which have forced Chinese Communist Party media to sidestep official restrictions on content or publish "soft" editions, such as weekend editions, to generate income.[17] Theories of state ownershipTwo contrasting theories of state control of the media exist; the public interest or Pigouvian theory states that government ownership is beneficial, whereas the public choice theory suggests that state control undermines economic and political freedoms. Public interest theoryThe public interest theory, also referred to as the Pigouvian theory,[18][needs update] states that government ownership of media is desirable.[19] Three reasons are offered. Firstly, the dissemination of information is a public good, and to withhold it would be costly even if it is not paid for. Secondly, the cost of the provision and dissemination of information is high, but once costs are incurred, marginal costs for providing the information are low and so are subject to increasing returns.[20] Thirdly, state media ownership can be less biased, more complete and accurate if consumers are ignorant and in addition to private media that would serve the governing classes.[20] However, Pigouvian economists, who advocate regulation and nationalisation, are supportive of free and private media.[21] Public interest theory holds that when operated correctly, government ownership of media is a public good that benefits the nation in question.[22] It contradicts the belief that all state media is propaganda and argues that most states require an unbiased, easily accessible, and reliable stream of information.[22] Public interest theory suggests that the only way to maintain an independent media is to cut it off from any economic needs, therefore a state-run media organization can avoid issues associated with private media companies, namely the prioritization of the profit motive.[23][verification needed] State media can be established as a mean for the state to provide a consistent news outlet while private news companies operate as well. The benefits and detriments of this approach often depend on the editorial independence of the media organization from the government.[24] Many criticisms of public interest theory center on the possibility of true editorial independence from the state.[22] While there is little profit motive, the media organization must be funded by the government instead which can create a dependency on the government's willingness to fund an entity may often be critical of their work.[7] The reliability of a state-run media outlet is often heavily dependent on the reliability of the state to promote a free press, many state-run media outlets in western democracies are capable of providing independent journalism while others in authoritarian regimes become mouthpieces for the state to legitimize their actions.[22] Public choice theoryThe public choice theory asserts that state-owned media would manipulate and distort information in favor of the ruling party and entrench its rule and prevent the public from making informed decisions, which undermines democratic institutions.[20] That would prevent private and independent media, which provide alternate voices allowing individuals to choose politicians, goods, services, etc. without fear from functioning. Additionally, that would inhibit competition among media firms that would ensure that consumers usually acquire unbiased, accurate information.[20] Moreover, this competition is part of a checks-and-balances system of a democracy, known as the Fourth Estate, along with the judiciary, executive and legislature.[20] States are dependent on the public for their legitimacy that allows them to operate.[25] The flow of information becomes critical to their survival, and public choice theory argues that states cannot be expected to ignore their own interests, and instead the sources of information must remain as independent from the state as possible.[22] Public choice theory argues that the only way to retain independence in a media organization is to allow the public to seek the best sources of information themselves.[26] This approach is effective at creating a free press that is capable of criticizing government institutions and investigating incidents of government corruption.[22] Those critical of the public choice theory argue that the economic incentives involved in a public business force media organizations to stray from unbiased journalism and towards sensationalist editorials in order to capture public interest.[27] This has become a debate over the effectiveness of media organizations that are reliant on the attention of the public.[27] Sensationalism becomes the key focus and turns away from stories in the public interest in favor of stories that capture the attention of the most people.[26] The focus on sensationalism and public attention can lead to the dissemination of misinformation to appease their consumer base.[26] In these instances, the goal of providing accurate information to the public collapses and instead becomes biased toward a dominant ideology.[26] Determinants of state controlBoth theories have implications regarding the determinants and consequences of ownership of the media.[28] The public interest theory suggests that more benign governments should have higher levels of control of the media which would in turn increase press freedom as well as economic and political freedoms. Conversely, the public choice theory affirms that the opposite is true - "public spirited", benevolent governments should have less control which would increase these freedoms.[29] Generally, state ownership of the media is found in poor, autocratic non-democratic countries with highly interventionist governments that have some interest in controlling the flow of information.[30] Countries with "weak" governments do not possess the political will to break up state media monopolies.[31] Media control is also usually consistent with state ownership in the economy.[32] As of 2002, the press in most of Europe (with the exception of Belarus, Russia and Ukraine) is mostly private and free of state control and ownership, along with North and South America (with the exception of Cuba and Venezuela)[33] The press "role" in the national and societal dynamics of the United States and Australia has virtually always been the responsibility of the private commercial sector since these countries' earliest days.[34] Levels of state ownership are higher in some African countries, the Middle East and some Asian countries (with the exception of Japan, India, Indonesia, Mongolia, Nepal, the Philippines, South Korea and Thailand where large areas of private press exist.) Full state monopolies exist in China, Myanmar, and North Korea.[33] Consequences of state ownershipIssues with state media include complications with press freedom and journalistic objectivity. According to Christopher Walker in the Journal of Democracy, "authoritarian or totalitarian media outlets" take advantage of both domestic and foreign media due to state censorship in their native countries and the openness of democratic nations to which they broadcast. He cites China's CCTV, Russia's RT, and Venezuela's TeleSUR as examples.[35] Surveys find that state-owned television in Russia is viewed by the Russian public as one of the country's most authoritative and trusted institutions.[36][37] Press freedom

Nations such as Denmark, Norway and Finland that have both the highest degree of freedom of press and public broadcasting media. Compared to most autocratic nations which attempt to limit press freedom to control the spread of information.[7] A 2003 study found that government ownership of media organizations was associated with worse democratic outcomes.[22] "Worse outcomes" are associated with higher levels of state ownership of the media, which would reject Pigouvian theory.[39] The news media are more independent and fewer journalists are arrested, detained or harassed in countries with less state control.[40] Harassment, imprisonment and higher levels of internet censorship occur in countries with high levels of state ownership such as Singapore, Belarus, Myanmar, Ethiopia, the People's Republic of China, Iran, Syria, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.[40][41] Countries with a total state monopoly in the media like North Korea and Laos experience a "Castro effect", where state control is powerful enough that no journalistic harassment is required in order to restrict press freedom.[40] Historically, state media also existed during the Cold War in authoritarian states such as the Soviet Union, East Germany, Republic of China (Taiwan), Poland, Romania, Brazil and Indonesia. Civil and political rightsThe public interest theory claims state ownership of the press enhances civil and political rights; whilst under the public choice theory, it curtails them by suppressing public oversight of the government and facilitating political corruption. High to absolute government control of the media is primarily associated with lower levels of political and civil rights, higher levels of corruption, quality of regulation, security of property and media bias.[41][42] State ownership of the press can compromise election monitoring efforts and obscure the integrity of electoral processes.[43] Independent media sees higher oversight by the media of the government. For example, reporting of corruption increased in Mexico, Ghana and Kenya after restrictions were lifted in the 1990s, but government-controlled media defended officials.[44][45] Heavily influenced state media can provide corrupt regimes with a method to combat efforts by protestors.[7] Propaganda spread by state-media organizations can detract from accurate reporting and provide an opportunity for a regime to influence public sentiment.[22] Mass protests against governments considered to be authoritarian, such as those in China, Russia, Egypt, and Iran are often distorted by state-run media organizations in order to defame protesters and provide a positive light on the government's actions.[7][46][47][48] Economic freedomIt is common for countries with strict control of newspapers to have fewer firms listed per capita on their markets[49] and less developed banking systems.[50] These findings support the public choice theory, which suggests higher levels of state ownership of the press would be detrimental to economic and financial development.[41] This is due to state media being commonly associated with autocratic regimes where economic freedom is severely restricted and there is a large amount of corruption within the economic and political system.[27] See alsoNotes

References

External links

|