|

Ulmus americana

Ulmus americana, generally known as the American elm or, less commonly, as the white elm or water elm,[a] is a species of elm native to eastern North America. The trees can live for several hundred years. It is a very hardy species that can withstand low winter temperatures, but it is affected by Dutch elm disease. The wood was seldom utilized until the advent of mechanical sawing. It is the state tree of Massachusetts and North Dakota. DescriptionThe American elm is a deciduous tree which, under ideal conditions, can grow to heights of 21 to 35 meters (69 to 115 feet).[3] The trunk may have a diameter at breast height (dbh) of more than 1.2 m (4 ft), supporting a high, spreading umbrella-like canopy. The leaves are alternate, 7–20 centimeters (3–8 inches) long, with double-serrate margins and an oblique base. The leaves turn yellow in the fall. The perfect flowers are small, purple-brown and, being wind-pollinated, apetalous. The flowers are also protogynous, the female parts maturing before the male, thus reducing, but not eliminating, self-fertilization,[4] and emerge in early spring before the leaves. The fruit is a flat samara 2 cm (3⁄4 in) long by 1.5 cm broad, with a circular papery wing surrounding the single 4.5 millimeters (1⁄8 inch) seed. As in the closely related Ulmus laevis (European white elm), the flowers and seeds are borne on 1–3 cm long stems. American elm is wholly insensitive to daylight length (photoperiod), and will continue to grow well into autumn until injured by frost.[5] Ploidy is 2n = 56, or more rarely, 2n = 28.[6] For over 80 years, U. americana had been identified as a tetraploid, i.e. having double the usual number of chromosomes, making it unique within the genus. However, a study published in 2011 by the Agricultural Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture revealed that about 20% of wild American elms are diploid and may even constitute another species. Moreover, several triploid trees known only in cultivation, such as 'Jefferson', are possessed of a high degree of resistance to DED, which ravaged American elms in the 20th century. This suggests that the diploid parent trees, which have markedly smaller cells than the tetraploid, may too be highly resistant to the disease.[7][8]

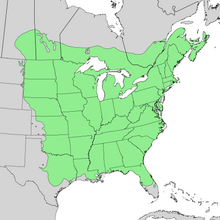

TaxonomyUlmus americana was first described and named by Carl Linnaeus in his Species Plantarum, published in 1753. No subspecies or varieties are currently recognized. Distribution and habitatThe American elm is native to eastern North America, occurring from Nova Scotia west to Alberta and Montana, and south to Florida and central Texas. It is an extremely hardy tree that can withstand winter temperatures as low as −40 °C (−40 °F).[9] The species occurs naturally in an assortment of habitats, most notably rich bottomlands, floodplains, stream banks, and swampy ground, although it also often thrives on hillsides, uplands and other well-drained soils.[10] On more elevated terrain, as in the Appalachian Mountains, it is most often found along rivers.[11] The species' wind-dispersed seeds enable it to spread rapidly as suitable areas of habitat become available.[10] American elm fruits in late spring (which can be as early as February and as late as June depending on the climate), the seeds usually germinating immediately, with no cold stratification needed (occasionally some might remain dormant until the following year). The species attains its greatest growth potential in the Northeastern US, while elms in the Deep South and Texas grow much smaller and have shorter lifespans, although conversely their survival rate in the latter regions is higher owing to the climate being less favorable to the spread of DED.[citation needed] In the United States, the American elm is a principal member of four major forest cover types: black ash-American elm-red maple; silver maple-American elm; sugarberry-American elm-green ash; and sycamore-sweetgum-American elm, with the first two of these types also occurring in Canada.[12] A sugar maple-ironwood-American elm cover type occurs on some hilltops near Témiscaming, Quebec.[13] EcologyThe leaves of the American elm serve as food for the larvae of a number of species of Lepidoptera. These include such butterflies as the Eastern Comma (Polygonia comma), Question Mark (Polygonia interrogationis), Mourning Cloak (Nymphalis antiopa), Painted Lady (Vanessa cardui) and Red-spotted Purple (Limenitis arthemis astyanax), as well as such moths as the Columbian Silkmoth (Hyalophora columbia) and the Banded Tussock Moth (Pale Tiger Moth) (Halysidota tessellaris).[14] Pests and diseasesThe American elm is susceptible to Dutch Elm Disease and to elm yellows. In North America, there are three species of elm bark beetles: one native, Hylurgopinus rufipes ("native elm bark beetle"); and two invasive, Scolytus multistriatus ("smaller European elm bark beetle") and Scolytus schevyrewi ("banded elm bark beetle"). Although intensive feeding by elm bark beetles can kill weakened trees,[15] their main impact is as vectors of DED. American elm is also moderately preferred for feeding and reproduction by the adult elm leaf beetle Xanthogaleruca luteola[16] and highly preferred for feeding by the Japanese beetle Popillia japonica[17] in the United States. U. americana is also the most susceptible of all the elms to verticillium wilt,[18] whose external symptoms closely mimic those of DED. However, the condition is far less serious, and afflicted trees should recover the following year. Dutch elm diseaseDutch elm disease (DED) is a fungal disease that has ravaged the American elm, causing catastrophic die-offs in cities across the range. It has been estimated that only approximately 1 in 100,000 American elm trees is DED-tolerant, most known survivors simply having escaped exposure to the disease.[19] However, in some areas still not infested by DED, the American elm continues to thrive, notably in Florida, Alberta and British Columbia. There is a notable grove of old American elm trees in Manhattan's Central Park. The trees there were apparently spared because of the grove's isolation in such an intensely urban setting.[citation needed] The American elm is particularly susceptible to disease because the period of infection often coincides with the period, approximately 30 days, of rapid terminal growth when new springwood vessels are fully functional. Spores introduced outside of this period remain largely static within the xylem and are thus relatively ineffective.[20] The American elm's biology in some ways has helped to spare it from obliteration by DED, in contrast to what happened to the American chestnut with the chestnut blight. The elm's seeds are largely wind-dispersed, and the tree grows quickly and begins bearing seeds at a young age. It grows well along roads or railroad tracks, and in abandoned lots and other disturbed areas, where it is highly tolerant of most stress factors. Elms have been able to survive and to reproduce in areas where the disease had eliminated old trees, although most of these young elms eventually succumb to the disease at a relatively young age. There is some reason to hope that these elms will preserve the genetic diversity of the original population, and that they eventually will hybridize with DED-resistant varieties that have been developed or that occur naturally. After 20 years of research, American scientists first developed DED-resistant strains of elms in the late 1990s.[19] Elms in forest and other natural areas have been less affected by DED than trees in urban environments due to lower environmental stress from pollution and soil compaction and due to occurring in smaller, more isolated populations. Fungicidal injections can be administered to valuable American elms, to prevent infection. Such injections generally are effective as a preventive measure for up to three years when performed before any symptoms have appeared, but may be ineffective once the disease is evident. CultivationIn the 19th and early 20th century, American elm was a common street and park tree owing to its tolerance of urban conditions, rapid growth, and graceful form. This however led to extreme overplanting of the species, especially to form living archways over streets, which ultimately produced an unhealthy monoculture of elms that had no resistance to disease and pests. Elms do not naturally form pure stands and trees used in landscaping were grown from a handful of cultivars, causing extremely low genetic diversity.[21] These trees' rapid growth and longevity, leading to great size within decades, made them popular before the advent of DED.[10] Ohio botanist William B. Werthner, discussing the contrast between open-grown and forest-grown American elms, noted that: "In the open, with an abundance of air and light, the main trunk divides into several leading branches which leave the trunk at a sharp angle and continue to grow upward, gradually diverging, dividing and subdividing into long, flexible branchlets whose ends, at last, float lightly in the air, giving the tree a round, somewhat flattened top of beautifully regular proportions and characteristically fine twiggery."[10] It is this distinctive growth form that is so valued in the open-grown American elms of street plantings, lawns, and parks; along most narrower streets, elms planted on opposite sides arch and blend together into a leafy canopy over the pavement. However, elms can assume many different sizes and forms depending on the location and climate zone. In 1926 the Klehm Nurseries of Arlington Heights, Illinois, wrote: "American Elms grown in the regular way from seedlings show extreme variability, growing up into trees of all shapes, some of them being very slow in growth while others are moderately rapid in development. The shapes run all the way from the true open excurrent growth to globular, or flat-topped, or pendant. As regards foliage, the leaves are from small to medium large, some shedding early and others late. This condition makes it difficult for the landscape architect to choose just the right trees to obtain the effect desired."[22] The classic vase-shaped elm was mainly the result of selective breeding of a few cultivars and is much less likely to occur in the wild.[23] American elms have been planted in North America beyond its natural range as far north as central Alberta. It also survives low desert heat at Phoenix, Arizona. Introductions across the Atlantic rarely prospered, even before the outbreak of DED. Introduced to the UK by James Gordon[1] in 1752, the American elm was noted to be far more susceptible to insect foliage damage than native elms.[24] The tree was propagated and marketed in the UK by the Hillier & Sons nursery, Winchester, Hampshire from 1945, with 450 sold in the period 1962 to 1977 when production ceased with the advent of the more virulent form of Dutch elm disease.[25][26] Introduced to Australasia, the tree was listed by Australian nurseries in the early 20th century. It is known to have been planted along the Avenue of Honour at Ballarat, Victoria and the Avenue of Honour in Bacchus Marsh, Victoria. In addition, a heritage-listed planting of American elms can be found along Grant Crescent in Griffith, Australian Capital Territory.[27] American elms are only rarely found in New Zealand.[28] CultivarsNumerous cultivars have been raised, originally for their aesthetic merit but more recently for their resistance to Dutch elm disease[29] The total number of named cultivars is circa 45, at least 18 of which have probably been lost to cultivation as a consequence of DED or other factors:

and others.[30] The disease-resistant selections made available to commerce to date include 'Valley Forge', 'New Harmony', 'Princeton', 'Jefferson', 'Lewis & Clark', 'Miller Park', 'St. Croix', 'Endurance', and a set of six different clones collectively known as 'American Liberty'.[31] The United States National Arboretum released 'Valley Forge' and 'New Harmony' in late 1995, after screening tests performed in 1992–1993 showed both had unusually high levels of resistance to DED. 'Valley Forge' performed especially well in these tests.[32] 'Princeton' has been in occasional cultivation since the 1920s. 'Princeton' gained renewed attention after its performance in the 1992–1993 screening tests showed that it also had a high degree of disease resistance. A later test performed in 2002–2003 confirmed the disease resistance of 'Princeton', 'Valley Forge' and 'New Harmony', as well as that of 'Jefferson'. Thus far, plantings of these four varieties generally appear to be successful. In 2005, approximately 90 'Princeton' elms were planted along Pennsylvania Avenue in front of the White House in Washington, D.C. The trees, whose maintenance the National Park Service (NPS) manages, remain healthy and are thriving.[33] However, it has been noted that U. americana cultivars are not recommended for more than singular plantings as they have unresolved DED and elm yellows concerns.[34] It has also been noted that monoculture plantings of U. americana cultivars, such as those along Pennsylvania Avenue, have disproportionate vulnerabilities to disease.[34] Further, long-term studies of 'Princeton' in Europe and the United States have suggested that the cultivar's resistance to DED may be limited (see Pests and diseases of 'Princeton'). The National Elm Trial evaluated 19 elm cultivars commercially available in the United States in scientific plantings throughout the nation to assess and compare the strengths and weaknesses of each. The trial, which started in 2005, lasted for ten years. Based on the trial's final ratings, the preferred cultivars of U. americana are 'New Harmony' and 'Princeton'.[35] 'Jefferson' was released to wholesale nurseries in 2004 and is becoming increasingly available for planting. However, 'Jefferson' has not been widely tested beyond Washington, D.C. The National Elm Trial provided no data on ‘Jefferson’ because an error in tree identification had occurred earlier in the nursery trade.[36] The error may still be causing nurseries to sell 'Princeton' elms that are mislabeled as 'Jefferson', although one can distinguish between the two cultivars as the trees mature.[34][37] In 2007, the 'Elm Recovery Project'[38] from the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, reported that cuttings from healthy surviving old elms surveyed across Ontario had been grown to produce a bank of resistant trees, isolated for selective breeding of highly resistant cultivars.[39] In 1993, Mariam B. Sticklen and James L. Sherald reported the results of NPS-funded experiments conducted at Michigan State University in East Lansing that were designed to apply genetic engineering techniques to the development of DED-resistant strains of American elm trees.[40] In 2007, AE Newhouse and F Schrodt of the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse reported that young transgenic American elm trees had shown reduced DED symptoms and normal mycorrhizal colonization.[41] Hybrids and hybrid cultivars

Thousands of attempts to cross the American elm with the Siberian elm U. pumila failed.[42] Attempts at the Arnold Arboretum using ten other American, European and Asiatic species also ended in failure, attributed to the differences in ploidy and operational dichogamy,[4] although the ploidy factor has been discounted by other authorities.[43] Success was eventually achieved with the autumn-flowering Chinese elm Ulmus parvifolia by the late Prof. Eugene Smalley towards the end of his career at the University of Wisconsin–Madison after he overcame the problem of keeping Chinese elm pollen alive until spring.[44] Only one of the hybrid clones was commercially released, as 'Rebella' in 2011 by the German nursery Eisele GmbH; the clone is not available in the United States. Other artificial hybridizations with American elm are rare, and now regarded with suspicion. Two such alleged successes by the nursery trade were 'Hamburg', and 'Kansas Hybrid', both with Siberian elm Ulmus pumila. However, given the repeated failure with the two species by research institutions, it is now believed that the "American elm" in question was more likely to have been the red elm, Ulmus rubra.[45] UsesWood

The American elm's wood is coarse, hard, and tough, with interlacing, contorted fibers that make it difficult to split or chop, and cause it to warp after sawing.[10] Accordingly, the wood originally had few uses, save for making hubs for wagon wheels.[10] Later, with the advent of mechanical sawing, American elm wood was used for barrel staves, trunk-slats, and hoop-poles, and subsequently became fundamental to the manufacture of wooden automobile bodies, with the intricate fibers holding screws unusually well.[10] Pioneer and traditional usesYoung twigs and branchlets of the American elm have tough, fibrous bark that has been used as a tying and binding material, even for rope swings for children, and also for making whips.[10] In cultureMary Eleanor Wilkins Freeman, in her 1903 book of short stories, Six Trees, wrote of the American elm:

On 21 March 1941 the American elm was made the state tree of Massachusetts. The designation was in commemoration of the fact that George Washington reputedly took command of the Continental Army under an elm.[47] Notable treesA number of mostly small to medium-sized American elms now survive in woodlands, suburban areas, and occasionally cities, where the survivors have often been relatively isolated from other elms and thus spared a severe exposure to the fungus. For example, in Central Park and Tompkins Square Park in New York City, stands of several large elms originally planted by Frederick Law Olmsted survive because of their isolation from neighboring areas in New York where there had been heavy mortality.[48] The Olmsted-designed park system in Buffalo, New York,[49] did not fare as well. A row of mature American elms lines Central Park along the entire length of Fifth Avenue from 59th to 110th Streets.[50] In Akron, Ohio, there is a very old elm tree that has not been infected. In historical areas of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, there are also a few mature American elms still standing — notably in Independence Square and the Quadrangle at the University of Pennsylvania, and also at the nearby campuses of Haverford College, Swarthmore College, and Pennsylvania State University, believed to be the largest remaining stand in the country.[51] There are several large American Elm trees in western Massachusetts. A large specimen, which stands on Summer Street in the Berkshire County town of Lanesborough, Massachusetts, has been kept alive by antifungal treatments. Rutgers University has preserved 55 mature elms on and in the vicinity of Voorhees Mall on the College Avenue Campus in New Brunswick, New Jersey in addition to seven disease-resistant trees that have been planted in this area of the campus in recent years.[52] The largest surviving urban forest of American elms in North America is believed to be in the city of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, where close to 200,000 elms remain. The city of Winnipeg spends $3 million annually to aggressively combat the disease utilizing Dursban Turf[53] and the Dutch Trig vaccine,[54] losing 1,500–4,000 trees per year. Governmental agencies, educational institutions or other organizations in most of the states that are within the United States maintain lists of champion or big trees that describe the locations and characteristics of those states' largest American elm trees (see List of state champion American elm trees). The current U.S. national champion American elm tree is located in Iberville Parish, Louisiana. When measured in 2010, the tree had a trunk circumference of 820 cm (324 in), a height of 34 m (111 ft) and an average crown spread of 24 m (79 ft).[55] The current Tree Register of the British Isles (TROBI) champion grows in Avondale Forest near Rathdrum, County Wicklow, Ireland. The tree had a height of 22.5 m (74 ft) and a dbh of 98 cm (39 in) (circumference of 308 cm or 121 in) when measured in 2000.[56] The tree replaced on the register a larger champion located in Woodvale Cemetery in Sussex, England, which in 1988 had a height of 27 metres (89 ft) and a diameter of 115 cm (45 in) or circumference of 361 cm (142 in).[57] A prime example of the species was the Sauble Elm,[58] which grew beside the banks of the Sauble River in Ontario, Canada, to a height of 43 m (140 ft), with a dbh of 196 cm (77 in) before succumbing to DED; when it was felled in 1968, a tree-ring count established that it had germinated in 1701. Other large or otherwise significant American elm trees have included: Treaty Elm The Treaty Elm, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In what is now Penn Treaty Park, the founder of Pennsylvania, William Penn, is said to have entered into a treaty of peace in 1683 with the native Lenape Turtle Clan under a picturesque elm tree immortalized in a painting by Benjamin West. West made the tree, already a local landmark, famous by incorporating it into his painting after hearing legends (of unknown veracity) about the tree being the location of the treaty. No documentary evidence exists of any treaty Penn signed beneath a particular tree. On March 6, 1810 a great storm blew the tree down. Measurements taken at the time showed it to have a circumference of 24 feet (7.3 m), and its age was estimated to be 280 years. Wood from the tree was made into furniture, canes, walking sticks and various trinkets that Philadelphians kept as relics.[59] Washington Elm (Massachusetts)The Washington Elm, Cambridge, Massachusetts. George Washington is said to have taken command of the American Continental Army under the Washington Elm in Cambridge on July 3, 1775. The tree survived until the 1920s and "was thought to be a survivor of the primeval forest". In 1872, a large branch fell from it and was used to construct a pulpit for a nearby church.[60] The tree, an American white elm, became a celebrated attraction, with its own plaque, a fence constructed around it and a road moved in order to help preserve it.[61] The tree was cut down (or fell—sources differ) in October 1920 after an expert determined it was dead. The city of Cambridge had plans for it to be "carefully cut up and a piece sent to each state of the country and to the District of Columbia and Alaska," according to The Harvard Crimson.[62] As late as the early 1930s, garden shops advertised that they had cuttings of the tree for sale, although the accuracy of the claims has been doubted. A Harvard "professor of plant anatomy" examined the tree rings days after the tree was felled and pronounced it between 204 and 210 years old, making it at most 62 years old when Washington took command of the troops at Cambridge. The tree would have been a little more than two feet in diameter (at 30 inches above ground) in 1773.[63] In 1896, an alumnus of the University of Washington, obtained a rooted cutting of the Cambridge tree and sent it to Professor Edmund Meany at the university. The cutting was planted, cuttings were then taken from it, including one planted on February 18, 1932, the 200th anniversary of the birth of George Washington, for whom Washington state is named. That tree remains on the campus of the Washington State Capitol. Just to the west of the tree is a small elm from a cutting made in 1979.[61] Washington Elm (District of Columbia)George Washington's Elm, Washington, D.C. George Washington supposedly had a favorite spot under an elm tree near the United States Capitol Building from which he would watch construction of the building. The elm stood near the Senate wing of the Capitol building until 1948.[60] Logan ElmThe Logan Elm that stood near Circleville, Ohio, was one of the largest American elms in the world. The 65-foot-tall (20 m) tree had a trunk circumference of 24 feet (7.3 m) and a crown spread of 180 feet (55 m).[64] Weakened by DED, the tree died in 1964 from storm damage.[64] The Logan Elm State Memorial commemorates the site and preserves various associated markers and monuments.[64] According to tradition, Chief Logan of the Mingo tribe delivered a passionate speech at a peace-treaty meeting under this elm in 1774.[64][65] "Herbie" Another notable American elm, named Herbie, was the tallest American elm in New England until it was cut down on January 19, 2010, after it succumbed to DED. Herbie was 110 feet (34 m) tall at its peak and had a circumference of 20.3 feet (6.2 m), or a diameter of approximately 6.5 feet (2.0 m). The tree stood in Yarmouth, Maine, where it was cared for by the town's tree warden, Frank Knight.[66] When cut down, Herbie was 217 years old. Herbie's wood is of interest to dendroclimatologists, who will use cross-sections of the trunk to help answer questions about climate during the tree's lifetime.[66] The Glencorradale ElmThe Glencorradale Elm on Prince Edward Island, Canada, is a surviving wild elm believed to be several hundred years old.[67] Survivor Tree An American elm located in a parking lot directly across the street from the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City survived the Oklahoma City bombing on April 19, 1995, that killed 168 people and destroyed the Murrah building. Damaged in the blast, with fragments lodged in its trunk and branches, it was nearly cut down in efforts to recover evidence. However, nearly a year later the tree began to bloom. Then known as the Survivor Tree, it became an important part of the Oklahoma City National Memorial, and is featured prominently on the official logo of the memorial.[68] Parliament Hill ElmThe Parliament Hill Elm was planted in Ottawa, Canada, in the late 1910s or early 1920s when Centre Block was rebuilt following the Great fire of 1916. The tree grew for approximately a century next to a statue of John A. Macdonald and was one of the few in the region to survive the spread of DED in the 1970s and 1980s.[69] Despite protests from Ottawa area environmentalists and resistance from Opposition Members of Parliament the tree was removed in April 2019 to make way for new Centre Block renovations.[70] Landscaped parksCentral Park New York City's Central Park is home to approximately 1,200 American elms. The oldest of these elms were planted during the 1860s by Frederick Law Olmsted, making them among the oldest stands of American elms in the world. The trees are particularly noteworthy along the Mall and Literary Walk, where four lines of American elms stretch over the walkway forming a cathedral-like covering. A part of New York City's urban ecology, the elms improve air and water quality, reduce erosion and flooding, and decrease air temperatures during warm days.[71] While the stand is still vulnerable to DED, in the 1980s the Central Park Conservancy undertook aggressive countermeasures such as heavy pruning and removal of extensively diseased trees. These efforts have largely been successful in saving the majority of the trees, although several are still lost each year. Younger American elms that have been planted in Central Park since the outbreak are of the DED-resistant 'Princeton' and 'Valley Forge' cultivars.[72] National Mall Several rows of American elm trees that the National Park Service first planted during the 1930s line much of the 1.9 miles (3.0 km) length of the National Mall in Washington, D.C. DED first appeared on the trees during the 1950s and reached a peak in the 1970s. The NPS used a number of methods to control the epidemic, including sanitation, pruning, injecting trees with fungicide and replanting with DED-resistant cultivars. The NPS combated the disease's local insect vector, the smaller European elm bark beetle (Scolytus multistriatus), by trapping and by spraying with insecticides. As a result, the population of American elms planted on the Mall and its surrounding areas has remained intact for more than 80 years.[73] Accessions

Art and photographyThe nobility and arching grace of the American Elm in its heyday, on farms, in villages, in towns and on campuses, were celebrated in the books of photographs of Wallace Nutting (Massachusetts Beautiful, N.Y. 1923, and other volumes in the series) and of Samuel Chamberlain (The New England Image, New York, 1962). Frederick Childe Hassam is notable among painters who have depicted American Elm.

Gallery

See also

Notes

References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![Scribner's magazine [1887]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b0/Scribner%27s_magazine_%281887%29_%2814778695871%29.jpg/120px-Scribner%27s_magazine_%281887%29_%2814778695871%29.jpg)

![Frederick Childe Hassam, 'Washington Arch, Spring' [1893]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Hassam_Washington_Arch_Spring.jpg/99px-Hassam_Washington_Arch_Spring.jpg)

![Frederick Childe Hassam, 'Church at Old Lyme' [1905]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a7/Church_at_Old_Lyme_Childe_Hassam.jpeg/106px-Church_at_Old_Lyme_Childe_Hassam.jpeg)

![Frederick Childe Hassam, 'The East Hampton Elms in May' [1920]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b1/Childe_Hassam%27s_1920_oil%2C_The_East_Hampton_Elms_in_May.jpg/120px-Childe_Hassam%27s_1920_oil%2C_The_East_Hampton_Elms_in_May.jpg)

![American elm in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Canada (August 2019). This tree was downed by Hurricane Fiona in 2022.[75]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/50/American_Elm_Tree%2C_Charlottetown%2C_PEI_-_August_2019.jpg/120px-American_Elm_Tree%2C_Charlottetown%2C_PEI_-_August_2019.jpg)

![American elm at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire (June 2015) This tree was cut down in 2022 due to Dutch Elm disease.[76]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f7/American_Elm%2C_Dartmouth_College%2C_Hanover%2C_NH_%28June_2015%29.jpg/120px-American_Elm%2C_Dartmouth_College%2C_Hanover%2C_NH_%28June_2015%29.jpg)