|

History of the territorial organization of SpainThe history of the territorial organization of Spain, in the modern sense, is a process that began in the 16th century with the dynastic union of the Crown of Aragon and the Crown of Castile, the conquest of the Kingdom of Granada and later the Kingdom of Navarre. However, it is important to clarify the origin of the toponym Spain, as well as the territorial divisions that existed previously in the current Spanish territory. Definition of SpainThe name Spain derives from Hispania, the name by which the Romans geographically designated the Iberian Peninsula as a whole, an alternative term to the name Iberia, preferred by Greek authors to refer to the same space. This name was kept after the fall of the Roman Empire as a designation of the peninsula under the Goths and among the Greco-Latin Christian world. After the Arab conquest, the part of the peninsula controlled by the Moors was called, for centuries, Al Ándalus or alternatively Spania, although the process of Reconquest ended up eliminating these names. The unification of the various kingdoms of that geographical region led to a correspondence between that region and a single state during the brief period of union of Spain and Portugal, which ended in 1640. Since then, Spain has been explicitly used to refer to the current country of that name, while Iberia is preferred to encompass Iberia and Portugal. This article will discuss the territorial organization of Spain throughout history, although the organization of other peninsular or bordering areas will be included when imposing the current borders is anachronistic. Pre-Roman periodThe Iberian Peninsula was originally occupied by peoples of different origins (Indo-European, Iberian or of unknown ethnogeny such as Cantabri, Varduli and Vascones). These peoples did not carry out any administrative division, organizing themselves as cities or tribes independent of each other. Later, some historians have tried to create families of tribes that share the same cultural characteristics, particularly distinguishing between Iberians in the Levant and south of the peninsula, Celts in the plateau and Vascones and Cantabri in the north. The limits between one area and another are a matter of discussion, with no agreement as to whether or not to include peoples such as the Lusitanians among the Celts or as peoples per se. These classifications do not imply that there was a common administrative organization among these tribes.

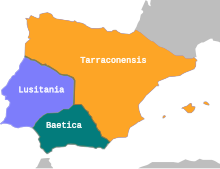

Roman division The Romans carried out various divisions of the peninsula throughout the history of their Empire:

Barbarian and Muslim kingdoms With the fall of the Roman Empire, the Suebi, Visigoths and other peoples occupied most of the peninsula. Finally, the Visigoths gained control of the entire peninsula in the 6th century after conquering the Suebi kingdom. They maintained the Roman provincial administrative division (under the name of "duchies") and even created new duchies, such as Asturias and Cantabria, and the province of Celtiberia and Carpetani. From 711, the Muslims conquered the peninsula and continued to control part of it until 1492, the year in which Granada was taken. The Muslim kingdom was divided into coras or kūras, all of which depended on a city. Later, as Muslim power declined, the coras became independent, creating small states with their own king, the so-called Taifa kingdoms. ReconquestWith the Reconquest several kingdoms were created: the Kingdom of Asturias (718), which claimed Visigothic legitimacy and became known as the Kingdom of León in 925, from which the Kingdom of Castile became independent in 1065 and the Kingdom of Portugal in 1139. The Kingdom of Galicia was also created in 910, intermittently independent of the Kingdom of León but subordinate to it (910–914, 926–929, 981–984, 1065–1073). With the Catholic Monarchs, each of these kingdoms maintained its own administrative divisions: in Castile, the provinces, and in the Crown of Aragon: districts in Aragon, vegueries in Catalonia and Mallorca, and in Valencia there were four governorates and eleven districts. 16th centuryCrown of Castile The territory of the kingdom of Castile was distributed among the 18 cities with the right to vote in Cortes and in turn subdivided into partidos, which in the census of 1591-1594 are not called that way, receiving in some cases also the name of province. These circumscriptions created at the end of the 16th century, which were sometimes called provinces, lacked any legal or administrative value and were merely fiscal in nature, so that it is important to avoid confusing this concept of province with the current one,[1] and did not constitute an administrative division at all. The only real administrative division existing at that time was the town and the municipality. There were also other structures, such as corregimientos, dioceses or lordships:

Crown of Aragon

Kingdom of NavarreIntendencies of 1720  Philip V created, taking as a base the pre-existing provinces created by the Austrias, the institution of the intendancies. Although it is true that these did not always coincide with the limits of the provinces, so there was some opposition to this division. Twenty were the intendancies then created: those of La Coruña, León, Valladolid, Burgos, Pamplona, Zaragoza, Barcelona, Salamanca, Ávila, Guadalajara, Toledo, Madrid, Ciudad Real, Valencia, Mérida, Seville, Córdoba, Granada, Palma and Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Ferdinand VI rearranged the limits of the intendancies, making them coincide with the provinces of the Austrias and the former kingdoms of Spain. Tomás González Hernández, headmaster of the Cathedral Church of Plasencia, reorganizes the Royal Archive of Simancas, after the despoilment suffered after the Napoleonic invasion. His work Census of the population of the Provinces and Districts of the Crown of Castile in the 16th century has constituted the only published source to know the Spanish population in the time of the Austrias. The archivist completes the so-called Book of the Millions with data from other regions: Catalonia, Basque Country, Navarre, Valencia and Aragon. Under the reign of Carlos III, on March 22, 1785, the Count of Floridablanca promoted the creation of a Prontuario or nomenclator of the towns of Spain and maps were drawn up to facilitate the control of the kingdom:

19th centuryDuring the 19th century, Spain witnessed a struggle between the Ancient Regime and the liberal State, with two antagonistic concepts of government. The liberal State needed a new territorial organization that would allow it to govern the country in a uniform manner, collect taxes and create a single market with equal laws for all. Soler Plan of 1799At the beginning of the 19th century, a new division of the territory of Spain was carried out on the basis of Enlightenment criticism of the previous division. This division was part of a project to reorganise the territory promoted by Miguel Cayetano Soler, general superintendent of finance, mainly with the intention of simplifying the tax system and rationalising the collection of taxes, so that the new reform gave a greater role to the delegates of the intendant —the subdelegates of revenue— and to the district boards. One of the most important points of the reform was the creation, by Royal Decree of 25 September 1799 and Instruction of 4 October of the same year, of six maritime provinces, Oviedo, Santander, Alicante, Cartagena, Malaga and Cadiz, which were separated, respectively, from the Intendencies of León, Burgos, Valencia, Murcia, Granada and Seville, all of which were very large provinces.[4] All the provinces created in 1799 have continued to exist in subsequent divisions up to the present day, with the exception of the period under the division into prefectures of 1810, and the province of Cartagena, which disappeared with the last and definitive provincial division of 1833, which is still in force today except for slight modifications. Prefectures of 1810The outbreak of the War of Independence in May 1808 established a new order under Napoleon, who put his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the throne. In 1810, the Josephine government tried to order the territory by dividing it into 38 prefectures, in the style of those established in France, and 111 sub-prefectures, according to the project of the engineer and mathematician José María Lanz.[5] The prefectures were to be named after geographical features, mainly rivers and capes. This division made a clean sweep of historical conditions, but it never came into force.  Thirty-eight peninsular prefectures were created, plus the Balearic and Canary Islands:

Although the War of Independence prevented the adoption of all these reforms, in 1812 a decree allowed Catalonia to be annexed to France until 1814 as a new region divided into four departments:

First attempt at provincesCortes of CadizIn 1811, the Cortes of Cadiz abolished the jurisdictional lordships, thus eliminating the division between seigneurialism and royalty, which, despite the restoration of absolutism by Ferdinand VII in 1814, would not come into force again. At the same time, the Cortes of Cadiz tried to create a new regime, also liberal, in which all the provinces would have the same obligations. The constitution of 1812 did not recognise the political personality of the former historical territories. This was approved by the deputies of all the provinces, including the American territories. The Cortes came up with a new system that did take into account the historical conditions. Thirty-two provinces were created, according to Floridablanca's nomenclature, with some corrections. But in 1813 they also commissioned a new provincial division from Felipe Bauzá, which determined 36 provinces, with seven subordinate provinces, based on historical criteria. But none of this was approved, and the return of Ferdinand VII meant a return to the Ancient Regime, with certain modifications. In 1817 Spain was divided into 29 intendencies and 13 consulates. Territorial division of 1822 After General Riego's uprising during the Liberal Triennium (1820–1823), the construction of the Liberal State was promoted, and with it a new provincial division, although the provincial councils of 1813 were recovered first. The idea was that this division would cover the whole country, without exception, and would be the single framework for administrative, governmental, judicial and economic activities, according to criteria of legal equality, unity and efficiency. The project was entrusted to the technicians Felipe Bauzá and José Agustín de Larramendi. In January 1822, the Cortes provisionally approved a provincial division of Spain into 52 provinces:[6]

Some of these provinces appear for the first time, such as Almería and Málaga (separated from the traditional Kingdom of Granada), Huelva (from the Kingdom of Seville), Calatayud and others appear with new names, such as the Vascongadas Provinces. This project makes few concessions to history, and is governed by criteria of population, extension and geographical coherence. There is a desire to go beyond historical names, preferring those of the capital cities. Nor are the traditional boundaries of the provinces respected, creating a new map. The enclaves of some provinces in others were eliminated if they belonged to different kingdoms, but many enclaves were preserved when they were within the same kingdom. In 1822 the provincial intendants were re-established as delegates of the Treasury. But the fall of the liberal government and the restoration of absolutism put an end to the project. In 1823, the provinces of the Ancient Regime were re-established, so the 1822 plan never came into force. Territorial reform of 1833 This reform carried out by Javier de Burgos in 1833 basically adopted the 1822 project, and has been maintained with some changes —partition of the Canary Islands, inclusion of Castilian comarcas to Valencian provinces— up to the present day. It divided the Spanish territory into 49 provinces on the basis of a rational criterion, with a relatively homogeneous size and eliminating most of the exclaves and enclaves typical of the Ancient Regime. At the same time, it grouped the provinces into regions with a merely classificatory character, without reserving for these any type of competence or administrative or jurisdictional body common to the provinces they grouped together. The territorial organization was as follows:

This provincial division was only implemented for the peninsular zone and adjacent islands, excluding the territories of Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, the Mariana Islands, the Caroline Islands, Palau, Equatorial Guinea and the North African sovereignties (Western Sahara, Ifni and Northern Morocco had not yet been incorporated). The main difference was that the Canary Islands had not been divided into two provinces to date, with Santa Cruz de Tenerife as their capital. In 1927, with the appearance of the province of Las Palmas, the number of provinces was increased to 50. Another difference is that most of the statutes of autonomy are based on this division, except those that have to do with the region of León, the region of Castilla la Vieja, the region of Castilla la Nueva and the region of Murcia. Attempts at regionalization in the 19th century1847  In an attempt to regionalize the peninsula, Patricio de la Escosura promulgated a decree on September 29, 1847 —which was suspended the same year—[7] the peninsula was divided into eleven general governments:

1873 In 1873, during the First Spanish Republic, a draft Constitution was drawn up defining Spain as a Federal Republic, made up of seventeen States with legislative, executive and judicial power. According to articles 92 and 93, these "States" would have "complete economic-administrative autonomy and all the political autonomy compatible with the existence of the Nation", as well as "the power to give themselves a political Constitution". This constitution, whose text is mainly attributed to Castelar, was never adopted. As it was a federal Constitution, nothing was said about the provinces, as sub-divisions were to be defined by the member States. The first article of the draft reads as follows:

1884 Later, in 1884, Segismundo Moret presented a new bill on January 6, 1884, which distributed the peninsula and adjacent islands into fifteen administrative and political regions, approximating the distribution of the Territorial Audiences, which also failed. Its distribution was as follows:[8]

1891 Seven years later there was another attempt at regionalization which was not consummated either, in this case promoted by Francisco Silvela. By means of a Royal Order of July 20, 1891 and a Bill on the same date, he announced his intention to organize the government of the peninsula, the Canary Islands and the Balearic Islands into thirteen regions. This project foresaw that the regions would reach an important consideration as an autonomous entity and assigned them the following distribution:[10]

Silvela's proposal would only materialize (and only briefly) in Cuba and Puerto Rico with the approval in 1897 of their respective autonomous charters. The only four peninsular regions that maintained their limits in all the regionalization projects were Catalonia, Galicia, Granada (called Andalusia Alta in the 1873 Constitution) and Seville (called Andalusia in the Escosura project and Andalusia Baja in the 1873 Constitution). 1897In an ephemeral way, a precedent for the regionalization of the administration began with the approval of: Regionalization in the Second Republic With the assumption in 1931 of the Second Spanish Republic, the possibility was introduced in the Constitution for the regions that made up Spain to become autonomous regions. Thus, in 1932 Catalonia approved its Statute of Autonomy, while the Vascongadas provinces did not make this possibility effective until 1936, when the Basque Autonomous Statute came into force. In Galicia, the Draft Statute of Autonomy of Galicia of 1936 was also included, which was approved by referendum by the Galician people but which, on the outbreak of the Civil War, did not enter into force, although its text was delivered to the president of the Spanish Cortes and admitted for processing by the latter. In the rest of the historical regions there were only timid attempts to approve statutes of autonomy, which did not go beyond the draft stage. All the regions, both Autonomous (with statute) and Non-Autonomous (without statute), are recognized as such in the Organic Law of the Court of Constitutional Guarantees of 1933, which granted them the right to appoint a regional member. Autonomous Regions

Non-Autonomous Regions

Franco's dictatorshipWith the end of the civil war and the dictatorship of Francisco Franco, the regions lose their political importance,[11] passing all territorial management to the deputations[12] and the Civil Governments of each province. The model of regions taught in schools was inherited from the separation of the Republic. In 1958, the territories of Western Sahara and Ifni were established as provinces, the latter until 1969 (when it was ceded to the Kingdom of Morocco) and the former until 1976 (when it was evacuated and handed over to Morocco and Mauritania). In 1964, the provinces of Rio Muni and Fernando Poo were organized in the Autonomous Regime of Equatorial Guinea, in force until its independence in 1968. It was not until democracy in 1975 that it made sense again to speak of the regions of Spain. State of the autonomous regions The Spanish Constitution was approved in 1978, recognizing the right to autonomy for the regions and nationalities that make up Spain. Thus began the process of constitution of the State of Autonomies. On July 31, 1981, UCD and PSOE approved the autonomous pacts by which Spain is divided into 17 autonomous communities and 2 autonomous cities (the latter will officially become autonomous in 1995). Each autonomous region is divided into several provinces —except the uniprovincial ones— which are the same, except for minor modifications, as those of Javier de Burgos' division. The nineteen autonomies are: Andalusia, Aragon, Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Cantabria, Castile-La Mancha, Castile and León, Catalonia, Ceuta, Community of Madrid, Foral Community of Navarre, Valencian Community, Extremadura, Galicia, Melilla, Basque Country, Principality of Asturias, Region of Murcia, La Rioja. See alsoReferencesNotes

Citations

Bibliography

Additional bibliography

External links

|

||||||