|

Jewish left

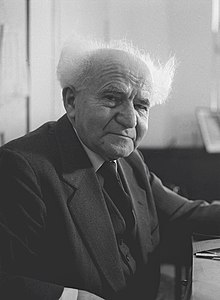

The Jewish left consists of Jews who identify with, or support, left-wing or left-liberal causes, consciously as Jews, either as individuals or through organizations. There is no one organization or movement which constitutes the Jewish left, however. Jews have been major forces in the history of the labor movement, the settlement house movement, the women's rights movement, anti-racist and anti-colonialist work, and anti-fascist and anti-capitalist organizations of many forms in Europe, the United States, Australia, Algeria, Iraq, Ethiopia, South Africa, and modern-day Israel.[1][2][3][4] Jews have a history of involvement in anarchism, socialism, Marxism, and Western liberalism. Although the expression "on the left" covers a range of politics, many well-known figures "on the left" have been Jews who were born into Jewish families and have various degrees of connection to Jewish communities, Jewish culture, Jewish tradition, or the Jewish religion in its many variants. HistoryJewish leftism has its philosophic roots in the Jewish Enlightenment, or Haskalah, led by thinkers such as Moses Mendelssohn, as well as the support of many European Jews such as Ludwig Börne for republican ideals in the aftermath of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a movement for Jewish Emancipation spread across Europe, strongly associated with the emergence of political liberalism, based on the Enlightenment principles of rights and equality under the law. Because liberals represented the political left of the time (see left-right politics), emancipated Jews, as they entered the political culture of the nations where they lived, became closely associated with liberal parties. Thus, many Jews supported the American Revolution of 1776, the French Revolution of 1789, and the European Revolutions of 1848; while Jews in England tended to vote for the Liberal Party, which had led the parliamentary struggle for Jewish Emancipation[5] – an arrangement called by some scholars "the liberal Jewish compromise".[6] The emergence of a Jewish working classIn the age of industrialisation in the late nineteenth century, a Jewish working class emerged in the cities of Eastern and Central Europe. Before long, a Jewish labour movement emerged too. The Jewish Labour Bund was formed in Lithuania, Poland, and Russia in 1897.[7] Distinctive Jewish socialist organizations formed and spread across the Jewish Pale of Settlement in the Russian Empire. There were also a significant number of people of Jewish origin who did not explicitly identify as Jews per se, but were active in anarchist, socialist, and social democratic as well as communist organizations, movements, and parties.[citation needed] As Zionism grew in strength as a political movement, socialist Zionist parties were formed, such as Ber Borochov's Poale Zion. There were non-Zionist left-wing forms of Jewish nationalism, such as territorialism (which called for a Jewish national homeland, but not necessarily in Palestine), autonomism (which called for non-territorial national rights for Jews in multinational empires), and the folkism, advocated by Simon Dubnow, (which celebrated the Jewish culture of the Yiddish-speaking masses).[citation needed] As Eastern European Jews migrated West from the 1880s, these ideologies took root in growing Jewish communities, such as London's East End, Paris's Pletzl, New York City's Lower East Side,[8] and Buenos Aires. There was a lively Jewish anarchist scene in London, a central figure of which was, the non-Jewish German thinker and writer Rudolf Rocker. The important Jewish socialist movement in the United States, with its Yiddish-language daily, The Forward, and trade unions such as the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers. Important figures in these milieux included Rose Schneiderman, Abraham Cahan, Morris Winchevsky, and David Dubinsky. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jews played a major role in the Social Democratic parties of Germany, Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Poland. Historian Enzo Traverso has used the term "Judeo-Marxism" to describe the innovative forms of Marxism associated with these Jewish socialists. These ranged from strongly cosmopolitan positions hostile to all forms of nationalism (as with Rosa Luxemburg and, to a lesser extent, Leon Trotsky) to positions more sympathetic to cultural nationalism (as with the Austromarxists or Vladimir Medem). In Soviets and against fascismAs with the American Revolution of 1776, the French Revolution of 1789, and the German revolution of 1848, many Jews worldwide welcomed the Russian Revolution of 1917, celebrating the fall of a regime that had presided over antisemitic pogroms, and believing that the new order in what was to become the Soviet Union would bring improvements in the situation of Jews in those lands. Many Jews became involved in Communist parties, constituting large proportions of their membership in many countries, including Great Britain and the U.S. There were specifically Jewish sections of many Communist parties, such as the Yevsektsiya in the Soviet Union. The Communist regime in the USSR pursued what could be characterised as ambivalent policies towards Jews and Jewish culture, at times supporting their development as a national culture (e. g., sponsoring significant Yiddish language scholarship and creating an autonomous Jewish territory in Birobidzhan), at times pursuing antisemitic purges, such as that in the wake of the so-called Doctors' plot. (See also Komzet.) With the advent of fascism in parts of Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, many Jews responded by becoming actively involved in the left, and particularly the Communist parties, which were at the forefront of the anti-fascist movement. For example, many Jewish volunteers fought in the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War (for instance in the American Abraham Lincoln Brigade and in the Polish-Jewish Naftali Botwin Company). Jews and leftists fought Oswald Mosley's British fascists at the Battle of Cable Street. This mass movement was influenced by the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee in the Soviet Union. In World War II, the Jewish left played a major part in resistance to Nazism. For example, Bundists and left Zionists were key in Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.[citation needed] Radical Jews in Central and Western EuropeAs well as the movements rooted in the Jewish working class, relatively assimilated middle class Jews in Central and Western Europe began to search for sources of radicalism in Jewish tradition. For example, Martin Buber drew on Hasidism in articulating his anarchist philosophy, Gershom Scholem was an anarchist and a kabbalah scholar, Walter Benjamin was equally influenced by Marxism and Jewish messianism, Gustav Landauer was a religious Jew and a libertarian communist, Jacob Israël de Haan combined socialism with Haredi Judaism, while left-libertarian Bernard Lazare became a passionately Jewish Zionist in 1897, but wrote two years later to Herzl – and by extension to the Zionist Action Committee – "You are bourgeois in thoughts, bourgeois in your feelings, bourgeois in your ideas, bourgeois in your conception of society."[9] In Weimar Germany, Walther Rathenau was a leading figure of the Jewish left.[citation needed] Socialist Zionism and the Israeli leftIn the twentieth century, especially after the Second Aliyah, socialist Zionism – first developed in Russia by the Marxist Ber Borochov and the non-Marxists Nachman Syrkin and A. D. Gordon – became a powerful force in the Yishuv, the Jewish settlement in Palestine. Poale Zion, the Histadrut labour union and the Mapai party played a major part in the campaign for an Israeli state, with socialist politicians like David Ben-Gurion and Golda Meir amongst the founders of the nation. At the same time, the kibbutz movement was an experiment in practical socialism. In the 1940s, many on the left advocated a binational state in Israel/Palestine, rather than an exclusively Jewish state. (This position was taken by Hannah Arendt and Martin Buber, for example). Since independence in 1948, there has been a lively Israeli left, both Zionist (the Labour Party, Meretz) and anti-Zionist (Palestine Communist Party, Maki). The Labour Party and its predecessors have been in power in Israel for significant periods since 1948. There are two worldwide groupings of left-wing Zionist organizations. The World Labour Zionist Movement, associated with the Labor Zionist tendency, is a loose association, including Avoda, Habonim Dror, Histadrut and Na'amat. The World Union of Meretz, associated with what was historically known as the Socialist Zionist tendency, is a loose association of the Israeli Meretz party, the Hashomer Hatzair Socialist Zionist youth movement, the Kibbutz Artzi Federation and the Givat Haviva research and study center. Both movements exist as factions within the World Zionist Organization, as well as regional or country-specific Zionist movements; the two roughly correspond to the interwar split between the Poale Zion Right (the tradition that led to Avoda) and the Poale Zion Left (Hashomer Hatzair, Mapam, Meretz). Apartheid South AfricaSouth Africa's Jewish left-wing was heavily involved in left-wing causes such as the anti-apartheid movement. The most famous member of the anti-apartheid Jewish left was Helen Suzman. There were also several left-wing Jewish defendants in the Rivonia Trial: Joe Slovo, Denis Goldberg, Lionel Bernstein, Bob Hepple, Arthur Goldreich, Harold Wolpe, and James Kantor. Contemporary Jewish left1960s–1990sAs the Jewish working class died out in the years after the Second World War, its institutions and political movements did too. The Arbeter Ring in England, for example, came to an end in the 1950s and Jewish trade unionism in the US ceased to be a major force at that time. There are, however, still some remnants of the Jewish working class organizations left today, including the Workmen's Circle, Jewish Labor Committee, and The Forward (newspaper) in New York, the International Jewish Labor Bund in Australia, and the United Jewish People's Order in Canada. The 1960s–1980s saw a renewal of interest among Western Jews in Jewish working class culture and the various radical traditions of the Jewish past. This led to the growth of a new sort of radical Jewish organization that was both interested in Yiddish culture, Jewish spirituality, and social justice. In the US, for example, between 1980 and 1992, New Jewish Agenda functioned as a national, multi-issue progressive membership organization with the mission of acting as a "Jewish voice on the Left and a Left voice in the Jewish Community". In 1990, Jews for Racial and Economic Justice formed to fight for "equitable distribution of economic and cultural resources and political power" in New York City. And in 1999, leftists broke from the LA chapter of the American Jewish Congress to form the Progressive Jewish Alliance. In Britain, the Jewish Socialists' Group and Rabbi Michael Lerner's Tikkun have similarly continued this tradition, while more recently groups like Jewdas have taken an even more eclectic and radical approach to Jewishness. In Belgium, the Union des progressistes juifs de Belgique is, since 1969, the heir of the Jewish Communist and Bundist Solidarité movement in the Belgian Resistance, embracing the Israeli refuseniks cause as well as of the undocumented immigrants in Belgium. 21st centuryDuring the first decade of the 2000s, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict became a defining element in the composition of the diasporic Jewish left. A new wave of grassroots leftist Jewish organizations formed to support Palestinian causes. Groups such as Jewish Voice for Peace, Independent Jewish Voices (Canada), Independent Jewish Voices (UK) and the International Jewish Anti-Zionist Network gave renewed voice to left-wing Jewish anti-Zionism. This perspective continues to be reflected in media outlets such as Mondoweiss and the Treyf Podcast.[10] 2014–2016: Jewish Left vs. the Jewish establishmentFollowing the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict, some leftist Jewish organizations in the US and Canada focused on directly challenging establishment Jewish organizations[11][12][13][14] such as the Jewish Federation, American Israel Public Affairs Committee, the Anti-Defamation League, and Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs, for their support for Israel's actions during the conflict. In the US, this intra-community conflict expanded to domestic politics following the 2016 United States presidential election.[15] Groups such as IfNotNow, Jewish Voice for Peace, and Jews for Racial and Economic Justice (JFREJ) began organizing under the banner of #JewishResistance to "challenge institutional Jewish support for the Trump administration and affiliated white nationalists".[16]  According to exit polls, 71% of American Jews voted Democratic during the 2016 US presidential election.[17] Over the last decade, the Jewish vote has gone to Democrats by 76–80%[18] in each election. A large majority of American Jews also report feeling somewhat or very attached to Israel.[19] Increasingly, however, young Jews are becoming more critical of the Israeli government and feel more sympathetic towards Palestinians than older American Jews.[20] Post-2016 growthAfter the 2016 United States presidential election, the Jewish left saw a significant upsurge in the US.[21] New Jewish initiatives such as Never Again Action formed to address the US government's expanding practice of migrant detention.[22] Many Jewish organizations, such as Bend the Arc, T'ruah, JFREJ, Jewish Voice for Peace, and IfNotNow joined this effort under the banner of #JewsAgainstICE.[23] New Jewish initiatives also formed to specifically address rising antisemitism and white nationalism in the US, such as the Outlive Them network,[24] Fayer,[25] and the Muslim-Jewish Anti-Fascist Front.[26] This period saw the creation of new leftist Jewish media outlets as well. Protocols,[27] a journal of culture and politics, began publishing in 2017. Jewish Currents, first published in 1946, gained a new editorial team of millennial Jews who relaunched the publication in 2018. And the Treyf Podcast, started in 2015, documented much of the growth of the US Jewish left during this period. This period also saw a renewed interest in Jewish Anarchism among the US Jewish left. This interest was aided by the publication of new books on the subject, such as Kenyon Zimmer's 2015 Immigrants against the State, and the reissuing of documentaries such as The Free Voice of Labor,[28] which details the final days of the Fraye Arbeter Shtime. In January 2019, The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research organized a special conference on Yiddish anarchism in New York City, which drew over 450 people.[29] Following this conference, a national Jewish Anarchist convergence was called in Chicago.[30] 2023–present upsurgeA new wave of Jewish left activity began in late 2023. This upsurge was part of the wider international mobilization in response to Israel's invasion of the Gaza Strip following the 2023 Hamas-led attack on Israel.[31] [32] According to Jay Ulfeder, research project manager at Harvard's Nonviolent Action Lab, this period saw "the largest and broadest pro-Palestinian mobilization in U.S. history."[33] This included the largest-ever Jewish American demonstration in support of Palestine[34] and the largest-ever pro-Palestine demonstration in US history. Many new Jewish leftist groups and coalitions were formed during this period, including Jews Say No to Genocide (Toronto, ON),[35][36] the Tzedek Collective (Victoria, BC),[37][38] Gliklekh in Goles (Vancouver, BC),[39] Shoresh (US),[40][41] and Rabbis for Ceasefire (US),[42][43] while existing anti-Zionist Jewish groups like Jewish Voice for Peace experienced an influx of thousands of new members.[44] Liberal Zionist Jewish groups generally took an opposing position to the Jewish left during this period, moving closer to the Jewish mainstream.[45] J Street and the Anti-Defamation League, for example, both opposed a ceasefire and voiced support for continued Israeli military action in the Gaza Strip, positions that led to waves of staff dissent and resignations.[46][47][48][49] By January 2024, J Street had called for a qualified end to Israel's military campaign[50] while the Anti-Defamation League continued to oppose anti-Zionist and other Jewish left groups calling for a ceasefire, characterizing them as "hate groups"[51] and working with law enforcement to police campus activism critical of Israel.[52][53][54] Ten liberal and progressive Zionist Jewish organizations, Ameinu, Americans for Peace Now, Habonim Dror North America, Hashomer Hatzair, The Jewish Labor Committee, J Street, The New Israel Fund, Partners for Progressive Israel, Reconstructing Judaism, and T'ruah, formed the Progressive Israel Network in 2019.[55] Many of these groups experienced internal dissent related to their support for Israel in the years leading up to the Israel–Hamas War[56][57][58][59] and staff at almost all Progressive Israel Network groups signed an open letter calling for a ceasefire following the Israeli invasion of the Gaza Strip. [60][61][47] Despite this, many Progressive Israel Network groups attended the March for Israel during the 2023 Israel-Hamas war under the flag of a "Peace Bloc".[62][63] Mari Cohen, reporting on the march for Jewish Currents, wrote that by "attending the November 14th March for Israel and refusing to call for a ceasefire, many progressive Jewish groups have cast their lot with the Jewish mainstream."[45] Contemporary Israeli leftOperating in a parliamentary governmental system based on proportional representation, left-wing political parties and blocs in Israel have been able to elect members of the Knesset with varying degrees of success. Over time, those parties have evolved, with some merging, others disappearing, and new parties arising. Israeli left-wing parties have included:

Notable figures in these parties have included: Amir Peretz, Meir Vilner, Shulamit Aloni, Uri Avnery, Yossi Beilin, Ran Cohen, Matti Peled, Amnon Rubinstein, Dov Khenin and Yossi Sarid. British Jewish leftBritish Jews have been influential in the left-wing politics of the United Kingdom for many years, especially in the main social democratic/socialist party, the Labour Party, but also in the socially liberal Liberal Democrats. During the years when the Liberal Party was Britain's main party of the left, two Jews in particular attained high office: Herbert Samuel, who led the Liberal Party from 1930 to 1935, and Rufus Isaacs, the only British Jew to have been created a Marquess. Other notable Liberal Jews of the 1800s and early 1900s included: Lionel de Rothschild, the first Jew to serve as an MP, Sir David Salomons, Sir Francis Goldsmid, Sir George Jessel, Arthur Cohen, The Lord Swaythling, Edward Sassoon, The Lord Hore-Belisha, Edwin Montagu, Ignaz Trebitsch-Lincoln, and The Lord Wandsworth. In the early part of the twentieth century, the Liberal Party gave way to the more radical and socialist Labour Party. Leonard Woolf and Hugh Franklin were among the figures influential in the early Labour Party, and Jewish MPs like Barnett Janner, Sir Percy Harris and The Lord Nathan were among the radical Liberal MPs, many of whom switched from Liberal to Labour, economists like Harold Laski and Nicholas Kaldor and intellectuals like Victor Gollancz and Karl Mannheim provided the intellectual impetus for British socialism to take hold. Prominent early Labour MPs included The Lord Silkin, who became a Minister in Clement Attlee's government, Sydney Silverman, who abolished capital punishment in Britain, and The Lord Shinwell, one of the leaders of Red Clydeside who later became Secretary of State for War. At the end of the Second World War, the Labour Party entered government again, and several newly elected Labour MPs were Jewish, and often on the socialist left of the Party, radicalised by incidents like the Battle of Cable Street. Those MPs included Herschel Austin, Maurice Edelman, and Ian Mikardo, as well as Phil Piratin, one of only four MPs in British history to have represented the Communist Party of Great Britain. Several MPs elected in the 1940s and 1950s went on to be Ministers in Harold Wilson's governments of the 1960s and 1970s: The Lord Barnett, Edmund Dell, John Diamond, Reg Freeson, The Baroness Gaitskell, Myer Galpern, Gerald Kaufman, The Lord Lever of Manchester, Paul Rose, The Lord Segal, The Baroness Serota, The Lord Sheldon, John and Samuel Silkin, Barnett Stross, and David Weitzman. A prominent Jewish Labour politician in this era was Leo Abse, who put forward the private members' bill which decriminalised homosexuality and reformed the divorce laws in Britain. Robert Maxwell, a Labour MP during the 1964–66 Wilson government, eventually became a leading newspaper publisher when his holding company purchased Mirror Group Newspapers in 1984. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Labour Party experienced significant turbulence with the rise of the entryist Militant tendency (a Trotskyist group led by Ted Grant), and the centre-left Social Democratic Party (SDP) breaking away and forming an Alliance with the Liberal Party (who had two Jewish MPs, The Lord Carlile of Berriew and Clement Freud), later to unite as the Liberal Democrats. One such parliamentary defector to the SDP was Neville Sandelson, and the Keynesian economist The Lord Skidelsky also defected. Those Jewish Labour MPs who stuck with the party included Harry Cohen, Alf Dubs, Millie Miller, Eric Moonman, and David Winnick. During the late 1980s and 1990s, with the shift away from the socialist left of the party, and during Tony Blair's leadership of the Labour Party, notable senior Jewish politicians included Peter Mandelson, one of the architects of "New Labour", Peter Goldsmith, Baron Goldsmith, The Lord Beecham, and The Lord Gould of Brookwood. Mandelson, party fund-raiser The Lord Levy and Jack Straw (who is of partial Jewish ancestry), were accused by Tam Dalyell, MP, of being a "cabal of Jewish advisers" around Blair.[64] Several of Blair's Ministers and Labour backbenchers were Jewish or partially Jewish, including Barbara Roche, Dame Margaret Hodge, Fabian Hamilton, Louise Ellman, The Baroness King of Bow, and Gillian Merron. Labour donors during the 1990s and 2000s who were Jewish included David Abrahams, The Lord Bernstein of Craigweil, Richard Caring, Sir Trevor Chinn, Sir David Garrard, The Lord Gavron, Sir Emmanuel Kaye, Andrew Rosenfeld, The Lord Sainsbury of Turville, and Barry Townsley. Several of these were caught up in the Cash for Honours scandal.[citation needed] Under the government of Blair's successor, Gordon Brown, brothers David Miliband and Ed Miliband became members of the Cabinet. Their father was the Marxist academic Ralph Miliband. The brothers differed in their view of the party's future direction, and they fought a bitter leadership election against each other in 2010. Ed Miliband won the election and became the first Jewish leader of the Labour Party. One of Miliband's Shadow Cabinet members, Ivan Lewis, as well as advisers David Axelrod, Arnie Graf, and The Lord Glasman are all Jewish. Current Jewish Labour politicians include: William Bach, The Lord Bassam of Brighton, Michael Cashman, The Lord Grabiner, Ruth Henig, Margaret Hodge, The Lord Kestenbaum, Jonathan Mendelsohn, Janet Neel Cohen, Meta Ramsay, Ruth Smeeth, Alex Sobel, Catherine Stihler, Andrew Stone, Leslie Turnberg, and Robert Winston. Since the foundation of the Liberal Democrats, several Jews have achieved prominence: David Alliance, Luciana Berger, the aforementioned Alex Carlisle, Miranda Green, Olly Grender, Sally Hamwee, Evan Harris, Susan Kramer, Anthony Lester, Jonathan Marks, Julia Neuberger, Monroe Palmer, Paul Strasburger, and Lynne Featherstone, who became a Minister in the Coalition government 2010–15. Jewish groups on the left include Independent Jewish Voices, Jewdas, the Jewish Socialists' Group, Jewish Voice for Labour and Jews for Justice for Palestinians. The Jewish Labour Movement is affiliated to the Labour Party. See also

Further reading

References

External links |