|

Old Japanese

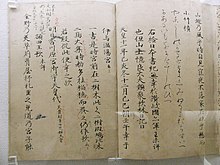

Old Japanese (上代日本語, Jōdai Nihon-go) is the oldest attested stage of the Japanese language, recorded in documents from the Nara period (8th century). It became Early Middle Japanese in the succeeding Heian period, but the precise delimitation of the stages is controversial. Old Japanese was an early member of the Japonic language family. No genetic links to other language families have been proven. Old Japanese was written using man'yōgana, using Chinese characters as syllabograms or (occasionally) logograms. It featured a few phonemic differences from later forms, such as a simpler syllable structure and distinctions between several pairs of syllables that have been pronounced identically since Early Middle Japanese. The phonetic realization of these distinctions is uncertain. Internal reconstruction points to a pre-Old Japanese phase with fewer consonants and vowels. As is typical of Japonic languages, Old Japanese was primarily an agglutinative language with a subject–object–verb word order, adjectives and adverbs preceding the nouns and verbs they modified and auxiliary verbs and particles appended to the main verb. Unlike in later periods, Old Japanese adjectives could be used uninflected to modify following nouns. Old Japanese verbs had a rich system of tense and aspect suffixes. Sources and dating Old Japanese is usually defined as the language of the Nara period (710–794), when the capital was Heijō-kyō (now Nara).[1][2] That is the period of the earliest connected texts in Japanese, the 112 songs included in the Kojiki (712). The other major literary sources of the period are the 128 songs included in the Nihon Shoki (720) and the Man'yōshū (c. 759), a compilation of over 4,500 poems.[3][4] Shorter samples are 25 poems in the Fudoki (720) and the 21 poems of the Bussokuseki-kahi (c. 752). The latter has the virtue of being an original inscription, whereas the oldest surviving manuscripts of all the other texts are the results of centuries of copying, with the attendant risk of scribal errors.[5] Prose texts are more limited but are thought to reflect the syntax of Old Japanese more accurately than verse texts do. The most important are the 27 Norito ('liturgies') recorded in the Engishiki (compiled in 927) and the 62 Senmyō (literally 'announced order', meaning imperial edicts) recorded in the Shoku Nihongi (797).[4][6] A limited number of Japanese words, mostly personal names and place names, are recorded phonetically in ancient Chinese texts, such as the "Wei Zhi" portion of the Records of the Three Kingdoms (3rd century AD), but the transcriptions by Chinese scholars are unreliable.[7] The oldest surviving inscriptions from Japan, dating from the 5th or early 6th centuries, include those on the Suda Hachiman Shrine Mirror, the Inariyama Sword, and the Eta Funayama Sword. Those inscriptions are written in Classical Chinese but contain several Japanese names that were transcribed phonetically using Chinese characters.[8][9] Such inscriptions became more common from the Suiko period (592–628).[10] Those fragments are usually considered a form of Old Japanese.[11] Of the 10,000 paper records kept at Shōsōin, only two, dating from about 762, are in Old Japanese.[12] Over 150,000 wooden tablets (mokkan) dating from the late 7th and early 8th century have been unearthed. The tablets bear short texts, often in Old Japanese of a more colloquial style than the polished poems and liturgies of the primary corpus.[13] Writing systemArtifacts inscribed with Chinese characters dated as early as the 1st century AD have been found in Japan, but detailed knowledge of the script seems not to have reached the islands until the early 5th century. According to the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, the script was brought by scholars from Baekje (southwestern Korea).[14] The earliest texts found in Japan were written in Classical Chinese, probably by immigrant scribes. Later "hybrid" texts show the influence of Japanese grammar, such as the word order (for example, the verb being placed after the object).[15] Chinese and Koreans had long used Chinese characters to write non-Chinese terms and proper names phonetically by selecting characters for Chinese words that sounded similar to each syllable. Koreans also used the characters phonetically to write Korean particles and inflections that were added to Chinese texts to allow them to be read as Korean (Idu script). In Japan, the practice was developed into man'yōgana, a complete script for the language that used Chinese characters phonetically, which was the ancestor of modern kana syllabaries.[16] This system was already in use in the verse parts of the Kojiki (712) and the Nihon Shoki (720).[17][18] For example, the first line of the first poem in the Kojiki was written with five characters:[19][20]

This method of writing Japanese syllables by using characters for their Chinese sounds (ongana) was supplemented with indirect methods in the complex mixed script of the Man'yōshū (c. 759).[21][22][23] SyllablesIn man'yōgana, each Old Japanese syllable was represented by a Chinese character. Although any of several characters could be used for a given syllable, a careful analysis reveals that 88 syllables were distinguished in early Old Japanese, typified by the Kojiki songs:[24][25]

As in later forms of Japanese, the system has gaps where yi and wu might be expected. Shinkichi Hashimoto discovered in 1917 that many syllables that have a modern i, e or o occurred in two forms, termed types A (甲, kō) and B (乙, otsu).[24][26] These are denoted by subscripts 1 and 2 respectively in the above table. The syllables mo1 and mo2 are not distinguished in the slightly later Nihon Shoki and Man'yōshū, reducing the syllable count to 87.[27][28] Some authors also believe that two forms of po were distinguished in the Kojiki.[29] All of these pairs had merged in the Early Middle Japanese of the Heian period.[30][31] The consonants g, z, d, b and r did not occur at the start of a word.[32] Conversely, syllables consisting of a single vowel were restricted to word-initial position, with a few exceptions such as kai 'oar', ko2i 'to lie down', kui 'to regret' (with conclusive kuyu), oi 'to age' and uuru, the adnominal form of the verb uwe 'to plant'.[33][34] Alexander Vovin argues that the non-initial syllables i and u in these cases should be read as Old Japanese syllables yi and wu.[35]

The rare vowel i2 almost always occurred at the end of a morpheme. Most occurrences of e1, e2 and o1 were also at the end of a morpheme.[37] The mokkan typically did not distinguish voiced from voiceless consonants, and wrote some syllables with characters that had fewer strokes and were based on older Chinese pronunciations imported via the Korean peninsula. For example,

TranscriptionSeveral different notations for the type A/B distinction are found in the literature, including:[39][40][41]

PhonologyThere is no consensus on the pronunciation of the syllables distinguished by man'yōgana.[42] One difficulty is that the Middle Chinese pronunciations of the characters used are also disputed, and since the reconstruction of their phonetic values is partly based on later Sino-Japanese pronunciations, there is a danger of circular reasoning.[43] Additional evidence has been drawn from phonological typology, subsequent developments in the Japanese pronunciation, and the comparative study of the Ryukyuan languages.[44] ConsonantsMiyake reconstructed the following consonant inventory:[45]

The voiceless obstruents /p, t, s, k/ had voiced prenasalized counterparts /ᵐb, ⁿd, ⁿz, ᵑɡ/.[45] Prenasalization was still present in the late 17th century (according to the Korean textbook Ch'ŏphae Sinŏ) and is found in some Modern Japanese and Ryukyuan dialects, but it has disappeared in modern Japanese except for the intervocalic nasal stop allophone [ŋ] of /ɡ/.[46] The sibilants /s/ and /ⁿz/ may have been palatalized before e and i.[47] Comparative evidence from Ryukyuan languages suggests that Old Japanese p reflected an earlier voiceless bilabial stop *p.[48] There is general agreement that word-initial p had become a voiceless bilabial fricative [ɸ] by Early Modern Japanese, as suggested by its transcription as f in later Portuguese works and as ph or hw in the Korean textbook Ch'ŏphae Sinŏ. In Modern Standard Japanese, it is romanized as h and has different allophones before various vowels. In medial position, it became [w] in Early Middle Japanese and has since disappeared except before a.[49] Many scholars, following Shinkichi Hashimoto, argue that p had already lenited to [ɸ] by the Old Japanese period, but Miyake argues that it was still a stop.[50] VowelsThe Chinese characters chosen to write syllables with the Old Japanese vowel a suggest that it was an open unrounded vowel /a/.[51] The vowel u was a close back rounded vowel /u/, unlike the unrounded /ɯ/ of Modern Standard Japanese.[52] Several hypotheses have been advanced to explain the A/B distinctions made in man'yōgana. The issue is hotly debated, and there is no consensus.[39] The traditional view, first advanced by Kyōsuke Kindaichi in 1938, is that there were eight pure vowels, with the type B vowels being more central than their type A counterparts.[53] Others, beginning in the 1930s but more commonly since the work of Roland Lange in 1968, have attributed the type A/B distinction to medial or final glides /j/ and /w/.[54][40] The diphthong proposals are often connected to hypotheses about pre-Old Japanese, but all exhibit an uneven distribution of glides.[40]

The distinction between mo1 and mo2 was seen only in Kojiki and vanished afterwards. The distribution of syllables suggests that there may have once been *po1, *po2, *bo1 and *bo2.[28] If that was true, a distinction was made between Co1 and Co2 for all consonants C except for w. Some take that as evidence that Co1 may have represented Cwo.[citation needed] AccentAlthough modern Japanese dialects have pitch accent systems, they were usually not shown in man'yōgana. However, in one part of the Nihon Shoki, the Chinese characters appeared to have been chosen to represent a pitch pattern similar to that recorded in the Ruiju Myōgishō, a dictionary that was compiled in the late 11th century. In that section, a low-pitch syllable was represented by a character with the Middle Chinese level tone, and a high pitch was represented by a character with one of the other three Middle Chinese tones. (A similar division was used in the tone patterns of Chinese poetry, which were emulated by Japanese poets in the late Asuka period.) Thus, it appears that the Old Japanese accent system was similar to that of Early Middle Japanese.[55] PhonotacticsOld Japanese words consisted of one or more open syllables of the form (C)V, subject to additional restrictions:

In 1934, Arisaka Hideyo proposed a set of phonological restrictions permitted in a single morpheme. Arisaka's Law states that -o2 was generally not found in the same morpheme as -a, -o1 or -u. Some scholars have interpreted that as a vestige of earlier vowel harmony, but it is very different from patterns that are observed in, for example, the Turkic languages.[57] MorphophonemicsTwo adjacent vowels fused to form a new vowel when a consonant was lost within a morpheme, or a compound was lexicalized as a single morpheme. The following fusions occurred:

Adjacent vowels belonging to different morphemes, or pairs of vowels for which none of the above fusions applied, were reduced by deleting one or other of the vowels.[65] Most often, the first of the adjacent vowels was deleted:[66][67]

The exception to this rule occurred when the first of the adjacent vowels was the sole vowel of a monosyllabic morpheme (usually a clitic), in which case the other vowel was deleted:[66][67]

Cases where both outcomes are found are attributed to different analyses of morpheme boundaries:[66][69]

Pre-Old JapaneseInternal reconstruction suggests that the stage preceding Old Japanese had fewer consonants and vowels.[73] ConsonantsInternal reconstruction suggests that the Old Japanese voiced obstruents, which always occurred in medial position, arose from the weakening of earlier nasal syllables before voiceless obstruents:[74][75]

In some cases, such as tubu 'grain', kadi 'rudder' and pi1za 'knee', there is no evidence for a preceding vowel, which leads some scholars to posit final nasals at the earlier stage.[56] Some linguists suggest that Old Japanese w and y derive, respectively, from *b and *d at some point before the oldest inscriptions in the 6th century.[76] Southern Ryukyuan varieties such as Miyako, Yaeyama and Yonaguni have /b/ corresponding to Old Japanese w, but only Yonaguni (at the far end of the chain) has /d/ where Old Japanese has y:[77]

However, many linguists, especially in Japan, argue that the Southern Ryukyuan voiced stops are local innovations,[78] adducing a variety of reasons.[79] Some supporters of *b and *d also add *z and *g, which both disappeared in Old Japanese, for reasons of symmetry.[80] However, there is very little Japonic evidence for them.[56][81] VowelsAs seen in § Morphophonemics, many occurrences of the rare vowels i2, e1, e2 and o1 arise from fusion of more common vowels. Similarly, many nouns having independent forms ending in -i2 or -e2 also have bound forms ending in a different vowel, which are believed to be older.[82] For example, sake2 'rice wine' has the form saka- in compounds such as sakaduki 'sake cup'.[82][83] The following alternations are the most common:

The widely accepted analysis of this situation is that the most common Old Japanese vowels a, u, i1 and o2 reflect earlier *a, *u, *i and *ə respectively, and the other vowels reflect fusions of these vowels:[87]

Thus the above independent forms of nouns can be derived from the bound form and a suffix *-i.[82][83] The origin of this suffix is debated, with one proposal being the ancestor of the obsolescent particle i (whose function is also uncertain), and another being a weakened consonant (suggested by proposed Korean cognates).[88] There are also alternations suggesting e2 < *əi, such as se2/so2- 'back' and me2/mo2- 'bud'.[82] Some authors believe that they belong to an earlier layer than i2 < *əi, but others reconstruct two central vowels *ə and *ɨ, which merged everywhere except before *i.[63][89] Other authors attribute the variation to different reflexes in different dialects and note that *əi yields e in Ryukyuan languages.[90] Some instances of word-final e1 and o1 are difficult to analyse as fusions, and some authors postulate *e and *o to account for such cases.[91] A few alternations, as well as comparisons with Eastern Old Japanese and Ryukyuan languages, suggest that *e and *o also occurred in non-word-final positions at an earlier stage but were raised in such positions to i1 and u, respectively, in central Old Japanese.[92][93] The mid vowels are also found in some early mokkan and in some modern Japanese dialects.[94] GrammarAs in later forms of Japanese, Old Japanese word order was predominantly subject–object–verb, with adjectives and adverbs preceding the nouns and verbs they modify and auxiliary verbs and particles consistently appended to the main verb.[95] nanipa Naniwa no2 GEN mi1ya court ni LOC wa 1S go2 GEN opo-ki1mi1 great-lord kuni land sir-as-urasi rule-HON-PRES 'In the Naniwa court, my lord might rule the land.' (Man'yōshū 6.933) Nominals tended to have simple morphology and little fusion, in contrast to the complex inflectional morphology of verbs.[96] Japanese at all stages has used prefixes with both nouns and verbs, but Old Japanese also used prefixes for grammatical functions later expressed using suffixes.[97] This is atypical of SOV languages, and may suggest that the language was in the final stage of a transition from a SVO typology.[97][98] NominalsPronounsMany Old Japanese pronouns had both a short form and a longer form with attached -re of uncertain etymology. If the pronoun occurred in isolation, the longer form was used. The short form was used with genitive particles or in nominal compounds, but in other situations either form was possible.[99] Personal pronouns were distinguished by taking the genitive marker ga, in contrast to the marker no2 used with demonstratives and nouns.[100]

Demonstratives often distinguished proximal (to the speaker) and non-proximal forms marked with ko2- and so2- respectively. Many forms had corresponding interrogative forms i(du)-.[103]

In Early Middle Japanese, the non-proximal so- forms were reinterpreted as hearer-based (medial), and the speaker-based forms were divided into proximal ko- forms and distal ka-/a- forms, yielding the three-way distinction that is still found in Modern Japanese.[105] NumeralsIn later texts, such as the Man'yōshū, numerals were sometimes written using Chinese logographs, which give no indication of pronunciation.[106] The following numerals are attested phonographically:[107]

The forms for 50 and 70 are known only from Heian texts.[108] There is a single example of a phonographically recorded compound number, in Bussokuseki 2:[109] mi1so-ti thirty-CL amar-i exceed-INF puta-tu two-CL no2 GEN katati mark 'thirty-two marks' This example uses the classifiers -ti (used with tens and hundreds) and -tu (used with digits and hundreds).[110] The only attested ordinal numeral is patu 'first'.[111] In Classical Japanese, the other ordinal numerals had the same form as cardinals. This may also have been the case for Old Japanese, but there are no textual occurrences to settle the question.[112] ClassifiersThe classifier system of Old Japanese was much less developed than at later stages of the language, and classifiers were not obligatory between numerals and nouns.[113] A few bound forms are attested phonographically: -tu (used with digits and hundreds), -ti (used with tens and hundreds), -ri (for people), -moto2, -pe1 (for grassy plants) and -ri (for days).[114] Many ordinary nouns could also be used either freely or as classifiers.[113] PrefixesOld Japanese nominal prefixes included honorific mi-, intensive ma- from ma 'truth', diminutive or affectionate wo- and a prefix sa- of uncertain function.[115] SuffixesOld Japanese nominals had suffixes or particles to mark diminutives, plural number and case. When multiple suffixes occurred, case markers came last.[116] Unmarked nouns (but not pronouns) were neutral as to number.[117] The main plural markers were the general-purpose ra and two markers restricted to animate nouns, do2mo2 (limited to five words) and tati.[118] The main case particles were[119]

The subject of a sentence was usually not marked.[123] There are a few cases in the Senmyō of subjects of active verbs marked with a suffix -i, which is thought to be an archaism that was obsolete in the Old Japanese period.[124][125] VerbsOld Japanese had a richer system of verbal suffixes than later forms of Japanese.[126] Old Japanese verbs used inflection for modal and conjunctional purposes.[127] Other categories, such as voice, tense, aspect and mood, were expressed by using optional suffixed auxiliaries, which were also inflected:[128] mayo1pi1-ki1-ni-ke1ri fray-come-PERF-MPST.CONCL 'had become frayed' (Man'yōshū 14.3453)[129] Inflected formsAs in later forms of Japanese, Old Japanese verbs had a large number of inflected forms. In traditional Japanese grammar, they are represented by six forms (katsuyōkei, 活用形) from which all the others may be derived in a similar fashion to the principal parts used for Latin and other languages:[130]

This system has been criticized because the six forms are not equivalent, with one being solely a combinatory stem, three solely word forms, and two being both.[142] It also fails to capture some inflected forms.[143] However, five of the forms are basic inflected verb forms, and the system also describes almost all extended forms consistently.[144] Conjugation classesOld Japanese verbs are classified into eight conjugation classes that were originally defined for the classical Japanese of the late Heian period. In each class, the inflected forms showed a different pattern of rows of a kana table. These rows correspond to the five vowels of later Japanese, but the discovery of the A/B distinction in Old Japanese showed a more refined picture.[145] Three of the classes are grouped as consonant bases:[146]

The distinctions between i1 and i2 and between e1 and e2 were eliminated after s, z, t, d, n, y, r and w. There were five vowel-base conjugation classes:

Early Middle Japanese also had a Shimo ichidan (lower monograde or e-monograde) category, consisting of a single verb kwe- 'kick', which reflected the Old Japanese lower bigrade verb kuwe-.[153][154][155][156]

The bigrade verbs seem to belong to a later layer than other verbs.[157] Many e-bigrade verbs are transitive or intransitive counterparts of consonant-base verbs.[158] In contrast, i-bigrade verbs tend to be intransitive.[159] Some bigrade bases also appear to reflect pre-Old-Japanese adjectives with vowel stems combined with an inchoative *-i suffix:[160][161][162]

CopulasOld Japanese had two copulas with limited and irregular conjugations:

The tu form had a limited distribution in Old Japanese, and disappeared in Early Middle Japanese. In later Japanese, the nite form became de, but these forms have otherwise endured to modern Japanese.[165] Verbal prefixesJapanese has used verbal prefixes conveying emphasis at all stages, but Old Japanese also had prefixes expressing grammatical functions, such as reciprocal or cooperative api1- (from ap- 'meet, join'), stative ari- (from ar- 'exist'), potential e2- (from e2- 'get') and prohibitive na-, which was often combined with a suffix -so2.[97][166] Verbal auxiliariesOld Japanese had a rich system of auxiliary elements that could be suffixed to verb stems and were themselves inflected, usually following the regular consonant-stem or vowel-stem paradigms, but never including the full range of stems found with full verbs.[167] Many of these disappeared in later stages of the language.[168] Tense and aspect were indicated by suffixes attached to the infinitive.[135] The tense suffixes were:

The perfective suffixes were -n- and -te-.[176][177] During the Late Middle Japanese period, the tense and aspect suffixes were replaced with a single past-tense suffix -ta, derived from -te + ar- 'exist' > -tar-.[126][178] Other auxiliaries were attached to the irrealis stem:

AdjectivesOld Japanese adjectives were originally nominals and, unlike in later periods, could be used uninflected to modify following nouns.[189][190] They could also be conjugated as stative verbs in two classes:[191]

The second class, with stems ending in -si, differed only in the conclusive form, whose suffix -si was dropped by haplology.[194] Adjectives of this class tended to express more subjective qualities.[195] Many of them were formed from a verbal stem by the addition of a suffix -si of uncertain origin.[196] Towards the end of the Old Japanese period, a more expressive conjugation was formed by adding the verb ar- 'be' to the infinitive, with the sequence -ua- reducing to -a-:[191]

Many adjectival nouns of Early Middle Japanese were based on Old Japanese adjectives that were formed with suffixes -ka, -raka or -yaka.[198][199] Focus constructionOld Japanese made extensive use of a focus construction, known as kakari-musubi ('hanging-tying'), that established a copular relation between a constituent marked with a focus particle and a predicate in the adnominal form, instead of the conclusive form usually found in declarative sentences.[200] The marked constituent was also typically fronted in comparison with its position in a corresponding declarative sentence.[201] The semantic effect (though not the syntactic structure) was often similar to a cleft sentence in English:[202] wa 1S ga GEN ko1puru love.ADN ki1mi1 lord so2 FOC ki1zo last.night no2 GEN yo1 night ime2 dream ni DAT mi1-ye-turu see-PASS-PERF.ADN 'It was my beloved lord that I saw last night in a dream.' (Man'yōshū 2.150) The particles involved were

The focus construction was common in Old Japanese and Classical Japanese, but disappeared after the Early Middle Japanese period.[211] It is still found in Ryukyuan languages, but is much less common there than in Old Japanese.[212] Dialects Although most Old Japanese writing represents the language of the Nara court in central Japan, some sources come from eastern Japan:[213][214][215][216]

They record Eastern Old Japanese dialects,[217] with several differences from central Old Japanese (also known as Western Old Japanese):

See alsoNotes

References

Works cited

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||