|

World Food Programme

The World Food Programme[a] (WFP) is an international organization within the United Nations that provides food assistance worldwide. It is the world's largest humanitarian organization[2][3] and the leading provider of school meals.[4] Founded in 1961, WFP is headquartered in Rome and has offices in 87 countries.[5] In 2023 it supported over 152 million people,[6] and it is present in more than 120 countries and territories.[7] In addition to emergency food relief, WFP offers technical and development assistance, such as building capacity for emergency preparedness and response, managing supply chains and logistics, promoting social safety programs, and strengthening resilience against climate change.[8] It is also a major provider of direct cash assistance, and provides passenger services for humanitarian workers through its management of the United Nations Humanitarian Air Service (UNHAS).[9][10] WFP is an executive member of the United Nations Sustainable Development Group,[11] a consortium of UN entities that aims to fulfil the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), with a priority to achieve SDG 2, "zero hunger", by 2030.[12] The World Food Programme was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2020 for its efforts to provide food assistance in areas of conflict and to prevent the use of food as a weapon of war and conflict.[13] HistoryWFP was established in 1961[14] after the 1960 Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Conference, when George McGovern, director of the US Food for Peace Programmes, proposed establishing a multilateral food aid programme. WFP launched its first programmes in 1963 by the FAO and the United Nations General Assembly on a three-year experimental basis, supporting the Nubian population at Wadi Halfa in Sudan. In 1965, the programme was extended to a continuing basis.[15] BackgroundWFP works across a broad spectrum of Sustainable Development Goals.[12] Food shortages, hunger, malnutrition, and foodborne illness lead to poor health, which affects other areas of sustainable development, such as education, employment, and poverty (Sustainable Development Goals Four, Eight, and One respectively).[12][16] FundingWFP operations are primarily funded by voluntary donations by governments worldwide, along with contributions from corporations and private donors.[17] In 2022, funding reached a record USD 14.1 billion – up by almost 50 percent from 2021 – against an operational funding need of USD 21.4 billion. The United States was the largest donor.[18] In 2023, the WFP received USD 8.3 billion in funding, likely marking the first time since 2010 that funding decreased from the previous year, creating a funding gap of 64%.[6] OrganizationGovernance, leadership and staffWFP is governed by an executive board that consists of representatives of 36 member states and provides intergovernmental support, direction, and supervision of WFP's activities. Of the 36 board members, 18 are elected by the United Nations Economic and Social Council and 18 by the Food and Agriculture Organization.[19] The European Union is a permanent observer in WFP and, as a major donor, participates in the work of its executive board.[20] WFP is headed by an executive director, who is appointed jointly by the UN Secretary-General and the director-general of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. The executive director is appointed for fixed five-year terms and is responsible for the administration of the organization as well as the implementation of its programmes, projects, and other activities.[21] Cindy McCain, previously Ambassador and Permanent Representative of the United States Mission to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Agencies in Rome, was appointed to the role in March 2023.[22] In March 2023, WFP had over 22,300 staff.  List of executive directorsSince 1992, all executive directors have been American. The following is a chronological list of those who have served as executive director of the World Food Programme:[23]

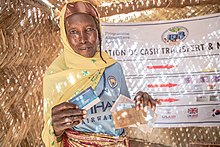

ActivitiesEmergenciesAbout two-thirds of WFP life-saving food assistance goes to people facing high degrees of food insecurity, predominantly resulting from violence and armed conflict.[24][25] Over 60% of the people facing hunger globally live in regions experiencing armed violence, which compounds with increased displacement, destruction of food systems, and increased humanitarian access challenges to pose massive risks to food security in the regions.[26] In 2023, more than 300 million people faced acute hunger globally.[6] WFP said it had "reached 152 million people with essential aid" in 2023.[6] The latest Hunger Hotspots outlook released June 2024 and co-published by WFP and FAO, emphasised that "acute food insecurity is likely to deteriorate further in 18 hotspots" between June and October 2024. These countries and country clusters face famine or risk of famine, with population already in or facing IPC Phase 5 (Catastrophe). Of those countries, Haiti, Mali, Palestine, South Sudan, and Sudan are classified as the most concerning.[25] WFP is also a first responder to sudden-onset emergencies. When floods struck Sudan in July 2020, it provided emergency food assistance to nearly 160,000 people.[27] WFP provided food as well as vouchers for people to buy vital supplies, while also planning recovery, reconstruction, and resilience-building activities, after Cyclone Idai struck Mozambique and floods washed an estimated 400,000 hectares of crops on early 2019.[28] WFP's emergency support is also preemptive in offsetting the potential impact of disasters. In the Sahel region of Africa, amidst economic challenges, climate change, and armed militancy, WFP's activities included working with communities and partners to harvest water for irrigation, restore degraded land, and support livelihoods through skills training.[29] It uses early-warning systems to help communities prepare for disasters. In Bangladesh, weather forecasting led to the distribution of cash to vulnerable farmers to pay for measures such as reinforcing their homes or stockpiling food ahead of heavy flooding.[30]  WFP is the lead agency of the Logistics Cluster, a coordination mechanism established by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC).[31] It also co-leads the Food Security Cluster.[32] The WFP-managed United Nations Humanitarian Air Service (UNHAS) serves over 300 destinations globally. WFP also manages the United Nations Humanitarian Response Depot (UNHRD), a global network of hubs that procure, store and transport emergency supplies for the organization and the wider humanitarian community. WFP logistical support, including its air service and hubs, has enabled staff and supplies from WFP and partner organizations to reach areas where commercial flights have not been available during the COVID-19 pandemic.[33] Climate change WFP provided cash to vulnerable groups ahead of torrential rains in Bangladesh in July 2019.[34] Its response to Hurricane Dorian in the Bahamas in September 2019 was assisted by a regional office in Barbados, which had been set up the previous year to enable better disaster preparedness and response. In advance of Dorian, WFP deployed technical experts in food security, logistics and emergency telecommunication to support a rapid needs assessment. Assessment teams also conducted an initial aerial reconnaissance mission with the aim to put teams on the ground as soon as possible.[35] Nutrition WFP works with governments, other UN agencies, NGOs and the private sector, increasing food security, supporting nutrition interventions, policies and programmes, that include school meals and food fortification.[36][37] School meals School meals encourage parents in vulnerable families to send their children to school, rather than work. They have proved highly beneficial in areas including education and gender equality, health and nutrition, social protection, local economies and agriculture.[38] WFP works with partners to ensure school feeding is part of integrated school health and nutrition programmes, which include services such as malaria control, menstrual hygiene and guidance on sanitation and hygiene.[39] Smallholder farmersWFP is a member of a global consortium that forms the Farm to Market Alliance, which helps smallholder farmers receive information, investment and support, so they can produce and sell marketable surplus and increase their income.[40][41] WFP connects smallholder farmers to markets in more than 40 countries. In 2008, WFP coordinated the five-year Purchase for Progress (P4P) pilot project. P4P assists smallholding farmers by offering them opportunities to access agricultural markets and become competitive players in the marketplace. The project spanned across 20 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America and trained 800,000 farmers in improved agricultural production, post-harvest handling, quality assurance, group marketing, agricultural finance, and contracting with WFP. The project resulted in 366,000 metric tons of food produced and generated more than US$148 million in income for its smallholder farmers.[42] Asset creationWFP's Food Assistance for Assets (FFA) programme provides cash or food-based transfers to address recipients' immediate food needs, while they build or boost assets, such as repairing irrigation systems, bridges, and land and water management activities.[43] FFA reflects WFP's drive towards food assistance and development rather than food aid and dependency. It does this by focusing on the assets and their impact on people and communities rather than on the work to realize them, a shift away from previous approaches such as Food or Cash for Work programmes and large public works programmes.[44] Cash assistance WFP uses cash transfers such as physical banknotes, a debit card or vouchers, aiming to give more choices to aid recipients and encourage the funds to be invested back into local economies. During the first half of 2022, WFP delivered US$1.6 billion in cash to 37 million people in 70 countries to alleviate hunger.[45] A 2022 study by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative concluded that the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN) cash programme "significantly reduced the incidence and intensity of multidimensional poverty" among the people receiving cash transfers.[46] Capacity buildingIn the most climate disaster-prone provinces of the Philippines, WFP is providing emergency response training and equipment to local government units, and helping set up automated weather stations.[47] Digital innovationWFP's digital transformation centres on deploying the latest technologies and data to help achieve zero hunger. The WFP Innovation Accelerator has sourced and supported more than 60 projects spanning 45 countries.[48] In 2017, WFP launched the Building Blocks programme. It aims to distribute money-for-food assistance to Syrian refugees in Jordan. The project uses blockchain technology to digitize identities and allow refugees to receive food by eye scanning.[49] WFP's low-tech hydroponics kits allow refugees to grow barley that feed livestock in the Sahara desert.[50] The SMP PLUS software is an AI-powered menu creation tool for school meals programmes worldwide [51] PartnershipsWFP works with governments, the private sector, UN agencies, international finance groups, academia, and more than 1,000 non-governmental organisations.[52] The WFP, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, and the International Fund for Agricultural Development reaffirmed their joint efforts to end global hunger, particularly amid the COVID-19 pandemic, during a joint meeting of their governing bodies in October 2020.[53] In the United States, Washington, D.C.–based 501(c)(3) organization World Food Program USA supports the WFP. The American organisation frequently donates to the WFP, though the two are separate entities for taxation purposes.[54] Aid transparencyWFP joined the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) in 2013 as its 150th member[55] and has regularly published data since then using the identifier XM-DAC-41140.[56] The organisation was assessed by Publish What You Fund and included in the 2024 Aid Transparency Index[57] with an overall score of 84.5, which is categorised as a "very good" score. ReviewsRecognition and awardsWFP won the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize for its "efforts for combating hunger", its "contribution to creating peace in conflicted-affected areas", and for acting as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of food as a weapon of war and conflict.[58][59] Receiving the award, executive David Beasley called for billionaires to "step up" and help source the US$5 billion WFP needs to save 30 million people from famine.[60] ChallengesIn 2018, the Center for Global Development ranked WFP last in a study of 40 aid programmes, based on indicators grouped into four themes: maximising efficiency, fostering institutions, reducing burdens, and transparency and learning. These indicators relate to aid effectiveness principles developed at the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (2005), the Accra Agenda for Action (2008), and the Busan Partnership Agreement (2011).[61] There is wide general debate on the net effectiveness of aid, including unintended consequences such as increasing the duration of conflicts and increasing corruption. WFP faces difficult decisions in working with some regimes.[62] Some surveys have shown internal culture problems at WFP, including sexual harassment.[63][64] See also

Notes

References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||