|

1940 United States presidential election

Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 5, 1940. Incumbent Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt defeated Republican businessman Wendell Willkie to be reelected for an unprecedented third term in office. Until 1988, this was the last time in which the incumbent's party won three consecutive presidential elections. It was also the fourth presidential election in which both major party candidates were registered in the same home state; the others have been in 1860, 1904, 1920, 1944, and 2016. The election was contested in the shadow of World War II in Europe, as the United States was finally emerging from the Great Depression. Roosevelt did not want to campaign for a third term initially, but was driven by worsening conditions in Europe.[3] He and his allies sought to defuse challenges from other party leaders such as James Farley and Vice President John Nance Garner. The 1940 Democratic National Convention re-nominated Roosevelt on the first ballot, while Garner was replaced on the ticket by Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace. Willkie, a dark horse candidate, unexpectedly defeated conservative Senator Robert A. Taft and Manhattan District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey on the sixth presidential ballot of the 1940 Republican National Convention. Roosevelt, acutely aware of strong isolationist and non-interventionist sentiment, promised there would be no involvement in foreign wars if he were reelected.[4] Willkie, who had not previously run for public office, conducted an energetic campaign, managing to revive Republican strength in areas of the Midwest and Northeast. He criticized perceived incompetence and waste in the New Deal, warned of the dangers of breaking the two-term tradition, and accused Roosevelt of secretly planning to take the country into World War II. However, Willkie's association with big business damaged his cause, as many working class voters blamed corporations and business leaders for the Great Depression. Roosevelt led in all pre-election polls and won a comfortable victory; his margins, though still significant, were less decisive than they had been in 1932 and 1936. NominationsDemocratic Party

Throughout the winter, spring, and summer of 1940, there was much speculation as to whether Roosevelt would break with longstanding tradition and run for an unprecedented third term. The two-term tradition, although not yet enshrined in the Constitution, had been established by George Washington when he refused to run for a third term in 1796; other former presidents, such as Ulysses S. Grant in 1880 and Theodore Roosevelt in 1912 had made serious attempts to run for a third term, but the former failed to be nominated, while the latter, forced to run on a third-party ticket, lost to Woodrow Wilson due to the split in the Republican vote. President Roosevelt refused to state definitely whether he would run for a third term. He even indicated to some ambitious Democrats that he would not run. Two of them thus decided to seek the Democratic nomination. These were James Farley, his former campaign manager, and Vice President John Nance Garner. Garner was a Texas conservative who had come to disagree with Roosevelt's liberal economic and social policies, and declined to run for a third term as vice president. However, as Nazi Germany swept through western Europe and menaced the United Kingdom in the summer of 1940, Roosevelt decided that only he had the necessary experience and skills to see the nation safely through the Nazi threat. He was aided by the party's political bosses, who feared that no Democrat except Roosevelt could defeat the popular Willkie.[5] At the July 1940 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Roosevelt easily swept aside challenges from Farley and Garner. Roosevelt picked Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace of Iowa to replace Garner on the ticket. An outspoken liberal who had been a Republican until he joined Roosevelt's cabinet, he met strong opposition from conservatives and party traditionalists. Wallace was also known as "eccentric" in his private life: some years earlier, he had been a follower of Theosophist mystic Nicholas Roerich. But Roosevelt insisted that without Wallace he would not run. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt came to Chicago to vouch for Wallace, and he won the vice-presidential nomination with 626 votes to 329 for House Speaker William B. Bankhead of Alabama.[6] Republican Party

In the months leading up to the opening of the 1940 Republican National Convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the Republican Party was deeply divided between the party's isolationists, who wanted to stay out of World War II at all costs, and the party's interventionists, who felt that the United Kingdom needed to be given all aid short of war to prevent Nazi Germany from conquering all of Europe. The three leading candidates for the Republican nomination - Senator Robert A. Taft from Ohio, Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg from Michigan, and District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey from New York - were all isolationists to varying degrees.[7] Taft was the leader of the conservative, isolationist wing of the Republican Party, and his main strength was in his native Midwestern United States and parts of the Southern United States. Dewey, the District Attorney for Manhattan, had risen to national fame as the "Gangbuster" prosecutor who had sent numerous infamous Mafia figures to prison, most notably Lucky Luciano, the organized-crime boss of New York City. Dewey had won most of the presidential primaries in the spring of 1940, and he came into the Republican Convention in June with the largest number of delegate votes, although he was still well below the number needed to win. Vandenberg, the senior Republican in the Senate, was the "favorite son" candidate of the Michigan delegation and was considered a possible compromise candidate if Taft or Dewey faltered. Former President Herbert Hoover was also spoken of as a compromise candidate. However, each of these candidates had weaknesses that could be exploited. Taft's outspoken isolationism and opposition to any American involvement in the European war convinced many Republican leaders that he could not win a general election, particularly as France fell to the Nazis in June 1940 and Germany threatened the United Kingdom. Dewey's relative youth—he was only 38 in 1940—and lack of any foreign-policy experience caused his candidacy to weaken as the Wehrmacht emerged as a fearsome threat. In 1940, Vandenberg was also an isolationist (he would change his foreign-policy stance during World War II) and his lackadaisical, lethargic campaign never caught the voters' attention. Hoover still bore the stigma of having presided over the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression. This left an opening for a dark horse candidate to emerge.[8]  A Wall Street-based industrialist named Wendell Willkie, who had never before run for public office, emerged as the unlikely nominee. Willkie, a native of Indiana and a former Democrat who had supported Franklin Roosevelt in the 1932 United States presidential election, was considered an improbable choice. Willkie had first come to public attention as an articulate critic of Roosevelt's attempt to break up electrical power monopolies. Willkie was the CEO of the Commonwealth & Southern Corporation, which provided electrical power to customers in eleven states. In 1933, President Roosevelt had created the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which promised to provide flood control and cheap electricity to the impoverished people of the Tennessee Valley. However, the government-run TVA would compete with Willkie's Commonwealth & Southern, and this led Willkie to criticize and oppose the TVA's attempt to compete with private power companies. Willkie argued that the government had unfair advantages over private corporations, and should thus avoid competing directly against them.[9] However, Willkie did not dismiss all of Roosevelt's social welfare programs, indeed supporting those he believed could not be managed any better by the free enterprise system. Furthermore, unlike the leading Republican candidates, Willkie was a forceful and outspoken advocate of aid to the Allies of World War II, especially the United Kingdom. His support of giving all aid to the British "short of declaring war" won him the support of many Republicans on the East Coast of the United States, who disagreed with their party's isolationist leaders in Congress. Willkie's persuasive arguments impressed these Republicans, who believed that he would be an attractive presidential candidate. Many of the leading press barons of the era, such as Ogden Reid of the New York Herald Tribune, Roy Howard of the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain and John and Gardner Cowles Jr. publishers of the Minneapolis Star and the Minneapolis Tribune, as well as The Des Moines Register and Look magazine, supported Willkie in their newspapers and magazines. Even so, Willkie remained a long-shot candidate; the May 8 Gallup Poll showed Dewey at 67% support among Republicans, followed by Vandenberg and Taft, with Willkie at only 3%. The German Army's rapid Blitzkrieg campaign into France in May 1940 shook American public opinion, even as Taft was telling a Kansas audience that America needed to concentrate on domestic issues to prevent Roosevelt from using the war crisis to extend socialism at home. Both Dewey and Vandenberg also continued to oppose any aid to the United Kingdom that might lead to war with Nazi Germany. Nevertheless, sympathy for the embattled British was mounting daily, and this aided Willkie's candidacy. By mid-June, little over one week before the Republican Convention opened, the Gallup poll reported that Willkie had moved into second place with 17%, and that Dewey was slipping. Fueled by his favorable media attention, Willkie's pro-British statements won over many of the delegates. As the delegates were arriving in Philadelphia, Gallup reported that Willkie had surged to 29%, Dewey had slipped five more points to 47%, and Taft, Vandenberg and Hoover trailed at 8%, 8%, and 6% respectively. Hundreds of thousands, perhaps as many as one million, telegrams urging support for Willkie poured in, many from "Willkie Clubs" that had sprung up across the country. Millions more signed petitions circulating everywhere. At the 1940 Republican National Convention itself, keynote speaker Harold Stassen, the Governor of Minnesota, announced his support for Willkie and became his official floor manager.[citation needed] Hundreds of vocal Willkie supporters packed the upper galleries of the convention hall. Willkie's amateur status and fresh face appealed to delegates as well as voters. Most of the delegations were selected not by primaries, but by party leaders in each state, and they had a keen sense of the fast-changing pulse of public opinion. Gallup found the same thing in polling data not reported until after the convention: Willkie had moved ahead among Republican voters by 44% to only 29% for the collapsing Dewey. As the pro-Willkie galleries chanted "We Want Willkie!" the delegates on the convention floor began their vote. Dewey led on the first ballot, but steadily lost strength thereafter. Both Taft and Willkie gained in strength on each ballot, and by the fourth ballot it was obvious that either Willkie or Taft would be the nominee. The key moments came when the delegations of large states such as Michigan, Pennsylvania, and New York left Dewey and Vandenberg and switched to Willkie, giving him the victory on the sixth ballot.[10] Willkie's nomination was one of the most dramatic moments in any political convention.[11] Having given little thought to whom he would select as his vice-presidential nominee, Willkie left the decision to convention chairman and Massachusetts Representative Joseph Martin, the House Minority Leader, who suggested Senate Minority Leader Charles L. McNary from Oregon. Despite the fact that McNary had spearheaded a "Stop Willkie" campaign late in the balloting, the convention picked him to be Willkie's running mate.[12] General electionPolling

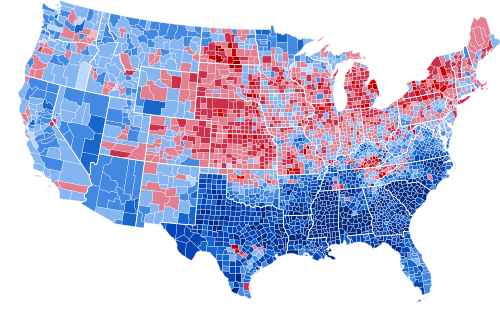

The Gallup Poll accurately predicted the election outcome.[13] However, the American Institute of Public Opinion, responsible for the Gallup Poll, avoided predicting the outcome, citing a four percent margin of error.[14] The Gallup Poll also found that, if there was no war in Europe, voters preferred Willkie over Roosevelt.[13] Fall campaign Willkie crusaded against Roosevelt's attempt to break the two-term presidential tradition, arguing that "if one man is indispensable, then none of us is free." Even some Democrats who had supported Roosevelt in the past disapproved of his attempt to win a third term, and Willkie hoped to win their votes. Willkie also criticized what he claimed was the incompetence and waste in Roosevelt's New Deal welfare programs. He stated that as president he would keep most of Roosevelt's government programs, but would make them more efficient.[15] However, many Americans still blamed business leaders for the Great Depression, and the fact that Willkie symbolized "Big Business" hurt him with many working-class voters. Willkie was a fearless campaigner; he often visited industrial areas where Republicans were still blamed for causing the Great Depression and where Roosevelt was highly popular. In these areas, Willkie frequently had rotten fruit and vegetables thrown at him and was heckled by crowds; still, he was unfazed.[16] Willkie also accused Roosevelt of leaving the nation unprepared for war, but Roosevelt's military buildup and transformation of the nation into the "Arsenal of Democracy" removed the "unpreparedness" charge as a major issue. Willkie then reversed his approach and charged Roosevelt with secretly planning to take the nation into World War II. This accusation did cut into Roosevelt's support. In response, Roosevelt, in a pledge that he would later regret, promised that he would "not send American boys into any foreign wars." The United Kingdom and Germany actively interfered throughout the election, hoping to exploit public sentiments and cultivate political contacts.[17][18][19] ResultsRoosevelt led in all pre-election opinion polls by various margins. On Election Day—November 5, 1940, he received 27.3 million votes to Willkie's 22.3 million, and in the Electoral College, he defeated Willkie by a margin of 449 to 82. Willkie did get over six million more votes than the Republican nominee in 1936, Alf Landon, and he ran strong in rural areas in the American Midwest, taking over 57% of the farm vote. Many counties in the Midwest have not voted for a Democrat since. Roosevelt, meanwhile, carried every American city with a population of more than 400,000 except Cincinnati, Ohio. Of the 106 cities with more than 100,000 population, he won 61% of the votes cast; in the Southern United States as a whole, he won 73% of the total vote. In the remainder of the country (the rural and small-town Northern United States), Willkie had a majority of 53%. In the cities, there was a class differential, with the white-collar and middle-class voters supporting the Republican candidate, and working class, blue-collar voters going for FDR. In the North, Roosevelt won 87% of the Jewish vote, 73% of the Catholics, and 61% of the nonmembers, while all the major Protestant denominations showed majorities for Willkie.[20] Roosevelt's net vote totals in the twelve largest cities decreased from 3,479,000 votes in the 1936 election to 2,112,000 votes, but it was still higher than his result from the 1932 election when he won by 1,791,000 votes.[21] Of the 3,094 counties/independent cities, Roosevelt won in 1,947 (62.93%) while Willkie carried 1,147 (37.07%). RecordsRoosevelt was the third of just four presidents in United States history to win re-election with a lower percentage of the electoral vote than in their prior elections, the other three were James Madison in 1812, Woodrow Wilson in 1916 and Barack Obama in 2012. Additionally, Roosevelt was the fourth of only five presidents to win re-election with a smaller percentage of the popular vote than in prior elections, the other four are James Madison in 1812, Andrew Jackson in 1832, Grover Cleveland in 1892, and Obama in 2012. This marked the first time since 1892 that the Democrats won the popular vote in three consecutive elections, and the first since 1840 where they won three consecutive elections. Although at a rate lower than 1936, Roosevelt maintained his strong majorities from labor unions, big city political machines, ethnic minority voters, and the traditionally Democratic Solid South. Roosevelt's third consecutive victory inspired the Twenty-second Amendment, limiting the number of terms a person may be president. As of 2024, Roosevelt was the sixth of eight presidential nominees to win a significant number of electoral votes in at least three elections, the others being Thomas Jefferson, Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson, Grover Cleveland, William Jennings Bryan, Richard Nixon, and Donald Trump. Of these, Jackson, Cleveland, and Roosevelt also won the popular vote in at least three elections. Jefferson, Cleveland, Roosevelt, and Trump were also their respective party's nominees for three consecutive elections. This was the first time that North Dakota voted for a losing candidate and the first time since 1892 that a Democrat won without Colorado, Kansas, and Nebraska. This was also the first time anyone won without Colorado and Nebraska since 1908, and Kansas since 1900. It was also the fourth presidential election in which both major party candidates were registered in the same home state; the others have been in 1860, 1904, 1920, 1944, and 2016. Willkie and McNary both died in 1944 (October 8, and February 25, respectively); the first, and to date only time both members of a major-party presidential ticket died during the term for which they sought election. Had they been elected, Willkie's death would have resulted in the Secretary of State becoming acting president for the remainder of the term ending on January 20, 1945, in accordance with the Presidential Succession Act of 1886.[22][23] 4.53% of Willkie's votes came from the eleven states of the former Confederacy, with him taking 21.65% of the vote in that region.[24]

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1940 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 31, 2005.Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005. Geography of results

Cartographic gallery

Results by stateSource:[25]

States that flipped from Democratic to RepublicanClose statesMargin of victory less than 1% (19 electoral votes):

Margin of victory less than 5% (192 electoral votes):

Margin of victory between 5% and 10% (83 electoral votes):

StatisticsCounties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

Foreign interferenceThe British government engaged covert intelligence operations to support Roosevelt, including the planting of false news stories, wiretaps, "October surprises", and other intelligence activities.[27][28] The German government had allocated $5 million as a campaign war chest via the German embassy to bribe Democratic delegates at the 1940 convention, using American businessman William Rhodes Davis as a conduit. Davis was sympathetic to the German cause after his meeting with Hermann Göring and was enlisted for this purpose. Later, he directed some of these funds towards supporting anti-Roosevelt radio broadcasts by the isolationist labor leader John L. Lewis, with the aim of impeding Roosevelt's re-election bid. Initially a supporter of Roosevelt in 1936, Davis had become disillusioned by 1940, and the two had grown apart over foreign policy. The German envoy in Mexico had also requested $160,000 to sway an unnamed Democratic Party operative in Pennsylvania to unseat interventionist Democratic Senator Joseph Guffey, who was a prominent critic of Nazi Germany. Davis was later identified as Abwehr agent C-80 following his death in August 1941.[18][29] See also

References

Works cited

Further reading

Primary sources

External links |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||