|

1916 United States presidential election

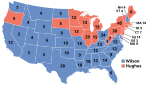

Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 7, 1916. Incumbent Democratic President Woodrow Wilson narrowly defeated former associate justice of the Supreme Court Charles Evans Hughes, the Republican candidate. In June, the 1916 Republican National Convention chose Hughes as a compromise between the conservative and progressive wings of the party. Hughes was on the Supreme Court in 1912 and was not involved in the bitter politics of that year. He defeated John W. Weeks, Elihu Root, and several other candidates on the third ballot. While conservative and progressive Republicans had been divided in the 1912 election between the candidacies of incumbent President William Howard Taft and former President Theodore Roosevelt, they largely united around Hughes in his bid to oust Wilson. Hughes remains, as of today, the only person to have served as a Supreme Court justice and later been a major party's presidential nominee. Wilson was renominated at the 1916 Democratic National Convention, as was Vice President Thomas R. Marshall, both without opposition. Hughes's running mate was Charles W. Fairbanks, who had been Theodore Roosevelt's vice president in his second term. The campaign took place against a background dominated by war — the Mexican Revolution and World War I. Although officially neutral in the European conflict, public opinion in the United States favored the Allied forces led by Great Britain and France against the German Empire and Austria-Hungary, due to the harsh treatment of civilians by the German Army and the militaristic character of the German and Austrian monarchies.[2] Despite their sympathy for the Allied forces, most American voters wanted to avoid involvement in the war and preferred to continue a policy of neutrality. Wilson's campaign used the popular slogans "He kept us out of war" and "America First" to appeal to those voters who wanted to avoid a war in Europe or with Mexico.[3][4][5] Hughes criticized Wilson for not taking the "necessary preparations" to face a conflict.[6] Although many saw Hughes as the favorite to win, Wilson after a hard-fought contest defeated him by nearly 600,000 votes out of about 18.5 million cast in the popular vote. Wilson secured a narrow majority in the Electoral College by sweeping the Solid South and winning several swing states with razor-thin margins. Wilson won California, the decisive state, by just 3,773 votes. Since the GOP was not as split as in 1912, Wilson did not have the same easy victory as he had four years earlier, losing his home state of New Jersey along with the states of Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Marshall's home state of Indiana, Iowa, Maine, Massachusetts, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, West Virginia (although he still won an electoral vote from the state), and Wisconsin. However, Wilson still managed to win two states that he had lost in 1912 (Utah and Washington), and fully won California after having only obtained two out of 13 electoral votes from California in 1912. Wilson became the first candidate to win reelection while losing both Pennsylvania and New York (Harry Truman and George W. Bush would later do the same). It was the first election since 1892 in which a Democrat was elected to a second term, and the first since 1832 in which a Democrat was elected to a consecutive second term. The United States entered the war in April 1917, one month after Wilson's second term began. NominationsDemocratic Party nomination

The 1916 Democratic National Convention was held in St. Louis, Missouri between June 14 and 16. Given Wilson's incumbency and enormous popularity within the party, he was overwhelmingly re-nominated. Vice President Thomas R. Marshall was also re-nominated with no opposition. Republican Party nomination

Other major candidates

Delegate selectionConvention The 1916 Republican National Convention was held in Chicago between June 7 and 10. A major goal of the party leaders was to heal the bitter split that ripped the party apart in 1912. Although several candidates were openly competing for the 1916 nomination — most prominently Senator Elihu Root of New York and Senator John W. Weeks of Massachusetts — the leaders wanted a moderate who would be acceptable to both factions. They turned to Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes, who had been serving on the court since 1910 and had the advantage of not having publicly spoken about political issues in six years. Although he had not actively sought the nomination, Hughes made it known that he would not turn it down. He won the nomination on the third ballot. Former Vice President Charles W. Fairbanks was nominated as his running mate. Hughes remains, as of today, the only serving Supreme Court justice to be nominated for president by a major political party.

Progressive Party nomination

Candidates considered

The Progressive Party re-nominated former President Theodore Roosevelt. For Vice President, Progressives nominated businessman John M. Parker of Louisiana, who had run an unsuccessful campaign. California Governor Hiram Johnson was suggested for renomination, and Raymond Robins, chairman of the party convention, was proposed, but both withdrew their names in favor of Parker. However, Roosevelt telegraphed the convention and declared that he could not accept their nomination and would be endorsing Republican nominee Charles Evans Hughes for the presidency. Roosevelt turned down the Progressive nomination for both personal and political reasons. He was convinced that running for president on a third-party ticket again would merely give the election to the Democrats and had developed a strong dislike for President Wilson. He also believed Wilson was allowing Germany and other warring nations in Europe to "bully" and intimidate the United States.[7][8][9] Former U.S. Representative Victor Murdock of Kansas pushed for a ticket consisting of William Jennings Bryan and Henry Ford but nothing came of it.[citation needed] Some, such as National Committeeman Harold L. Ickes, refused to consider endorsing Hughes. There was some talk of replacing Roosevelt with Hiram Johnson or Gifford Pinchot.[citation needed] All those discussed refused to consider the notion, and by this point, some leaders such as Henry Justin Allen had started to follow Roosevelt's lead and endorsed Hughes. Various state parties, such as those in Iowa and Maine, began to disband. Finally, when the Progressive Party National Committee met in Chicago on June 26, those in attendance begrudgingly endorsed Hughes; even those like Ickes who had vehemently refused to consider granting an endorsement to Hughes began to recognize that without Roosevelt the party had no electoral staying power. There had been a weak attempt to replace Roosevelt on the ticket with Victor Murdock, but the motion was defeated 31 to 15.[10] With Roosevelt refusing their nomination, the Progressive Party quickly fell into disarray. Most members returned to the Republican Party, but a substantial minority supported Wilson for his efforts in keeping the United States out of World War I. Without a presidential nominee, many in the party, notably vice-presidential nominee John M. Parker and Bainbridge Colby, remained steadfast in their refusal to support Hughes. Parker desired the presidential nomination himself. Colby, while opposed to the endorsement of Hughes, now considered a Progressive campaign impractical and privately supported Wilson. It appeared likely for a time that another convention would be called in early August, until a conference held among the remaining representatives of the party in Indianapolis decided against it, while also narrowly voting against filling the vacancy that had been caused by Roosevelt's refusal to be placed on the ticket (though Parker remained the vice-presidential nominee). Electoral tickets would still be put in place where the Progressive Party remained organized in the hopes of electing enough electors so as to possibly hold the balance of power in a close contest between the Democratic and Republican candidates. While running as the vice-presidential nominee, John Parker would endorse Woodrow Wilson for the presidency.[11][12] Socialist Party nomination

Other candidates

Eugene V. Debs and Charles Edward Russell declined to run for the nomination.[13] Debs, who had served as the party's presidential nominee since its foundation, chose to run for a seat in the United States House of Representatives from Indiana's 5th congressional district.[14] Allan Benson, a newspaper editor from New York, quickly came to dominate the field on a platform of his fervent opposition to militarism and proposal that all wars should be voted upon in a national referendum. Rather than a traditional nominating convention, the vote was conducted through a mail-order ballot, with Benson capturing 16,639 out of a total of 32,398 cast (to 12,264 for Maurer and 3,495 for Le Sueur). A vote for the vice-presidential nomination was jointly held with George Ross Kirkpatrick, a lecturer from New Jersey, winning the nomination 20,607 to 11,388 over Kate Richards O'Hare of Missouri.[15] Prohibition Party nomination

Other candidates

The twelfth Prohibition National Convention assembled in Saint Paul, Minnesota on July 19. Before the convention a number of figures were considered potential nominees for the presidency, among them former Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan, former Governor of New York William Sulzer, former Governor of Massachusetts Eugene Foss, former Governor of Indiana Frank Hanly, former General Nelson Miles, and former Alabama Congressman Richmond Hobson;[16] Sulzer and Hanly ultimately were the only two to actively campaign for the nomination. It was generally recognized early on that Hanly's nomination was favored with a supporter of his, Robert Patton, being named as permanent chairman of the convention. This culminated with the adoption of much of his program into the Party platform and his own nomination for the presidency, Hanly receiving 440 votes to Sulzer's 181.[17][18] Ira Landrith, a Presbyterian minister from Tennessee and member of the Flying Squadron of America was nominated for the vice presidency after other names were withdrawn from contention before the first ballot. General election  During the campaign, Edward M. House was Wilson's top campaign advisor. Hodgson says, "he planned its structure; set its tone; guided its finance; chose speakers, tactics, and strategy; and, not least, handled the campaign's greatest asset and greatest potential liability: its brilliant but temperamental candidate."[19] The Democrats built their campaign around the slogan, "He Kept Us Out of War," saying a Republican victory would mean war with both Mexico and Germany. Wilson's position was probably critical in winning the Western states.[20] Charles Evans Hughes advocated greater mobilization and preparedness for war.[21] With Wilson having successfully pressured the Germans to suspend unrestricted submarine warfare, it was difficult for Hughes to attack Wilson's peace platform. Instead, Hughes criticized Wilson's military interventions in Mexico, where the U.S. was supporting various factions in the Mexican Revolution.[22] Hughes also attacked Wilson for his support of various "pro-labor" laws (such as limiting the workday to eight hours), on the grounds that they were harmful to business interests. His criticisms gained little traction, however, especially among factory workers who supported such laws. Hughes was helped by the vigorous support of popular former President Theodore Roosevelt, and by the fact that the Republicans were still the nation's majority party at the time.[citation needed] Hughes made a key mistake in California. The 1912 split in Republican ranks remained a lingering issue, with two rival factions in California. Hughes decided to base his California campaign with the conservative Republican regulars instead of the Progressive faction. Hiram Johnson, the governor of California who had been Roosevelt's running mate in 1912, did endorse and speak for Hughes. However Johnson did not mobilize the Progressive faction and it saw Wilson as more of a true progressive. Wilson carried California by 3,773 votes (0.3%) and with it the Electoral College and the presidency.[23][24] Wilson's contingency plan had he lostIn the weeks prior to the election, Wilson began to worry that, were he to lose the race to Hughes, he would remain a lame duck until March 1917. For Wilson, this was problematic, given that the United States was likely on the eve of its entry into the First World War. Wilson, thus, privately floated a contingency plan: were Hughes to win, Wilson would immediately appoint Hughes secretary of state (a role which was, at the time, second-in-line to the presidency). Wilson and Vice President Marshall would both then resign, allowing Hughes to immediately become acting president, thereby avoiding a lengthy lame duck presidency.[25][26] This plan was first revealed publicly two decades later in the memoirs of Robert Lansing, Wilson's secretary of state, who, under the plan, would have had to have resigned or been dismissed in order to allow Hughes to assume that office.[27] Results32.1% of the voting age population and 61.8% of eligible voters participated in the election.[28] The result was exceptionally close and the outcome remained in doubt for some time. Some New York newspapers declared Hughes the winner on Wednesday morning, including The World and The Sun, which erroneously published that six states (California, Idaho, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Washington, and Wyoming) had voted for Hughes.[29] The official gazette of the Kingdom of Serbia also declared him the winner on 16 November 1916.[30] A popular legend from the campaign states that Hughes went to bed on election night thinking that he was the newly elected president. When a reporter tried to telephone him the next morning to get his reaction to Wilson's comeback, someone[a] answered the phone and told the reporter that "the president is asleep." The reporter retorted, "When he wakes up, tell him he isn't the president."[31][32] By Wednesday evening, Wilson had secured 254 electoral votes in the counting, needing either California or Minnesota to claim victory.[33] Democrats declared victory in California on Thursday afternoon, and the California Republican Party conceded defeat that night.[34] Wilson was the first Democratic president to win a second consecutive term since Andrew Jackson in 1832.[35] Vice-president Thomas R. Marshall also earned the distinction of becoming the first vice-president of any party elected to a second term since John C. Calhoun in 1828. As Calhoun had served as vice president under John Quincy Adams and was re-elected to serve under Andrew Jackson, Wilson and Marshall became the first incumbent ticket to win re-election since James Monroe and Daniel D. Tompkins in 1820. The electoral vote was one of the closest in U.S. history – with 266 votes needed to win, Wilson took 30 states for 277 electoral votes, while Hughes won 18 states and 254 electoral votes. Wilson was the second of just four presidents in United States history to win re-election with a lower percentage of the electoral vote than in their prior elections, after James Madison in 1812, Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940 and 1944 and Barack Obama in 2012. Wilson's popular vote margin of 3.1 percent was the smallest attained by a victorious sitting president since 1812 and retained that status until 2004. The total popular vote cast in 1916 exceeded that of 1912 by 3,500,000. The large total vote was an indication of an aroused public interest in the campaign. It was larger in every section, notably in the East North Central section. Some of this was due to the extension of suffrage to women in individual states. In Illinois, for example, the total vote was one million greater than in 1912. It increased by more than 260,000 in Kansas, and in Montana, it more than doubled. Wilson's vote was 9,126,868, an increase of nearly 3,000,000. There was a gain in every section and in every state. Hughes, the nominee of the united Republican Party, polled more votes by nearly 1,000,000 than had ever been cast for a Republican candidate. Among the third-party candidates, Benson's vote dropped to a little over half of what Eugene Debs had earned at the previous election, though this would still represent the best-ever showing of any Socialist candidate other than Debs. Hanly's performance would mark the last time the Prohibition Party exceeded one percent of the popular vote, with the party quickly declining into irrelevance after the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919. To date, this is the last presidential election in which North Dakota and South Dakota did not vote for the same candidate, with the only others being 1896 and 1912. This is the last time Illinois voted for a losing candidate until 1976, the last time Minnesota voted for a losing candidate until 1968, and the last time West Virginia voted for a losing candidate until 1952. It was the only time a Democrat was elected without winning West Virginia from the state's founding until 2008.[b] This is one of only four U.S. presidential elections in which the winner did not carry any of the three Rust Belt states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin; the others were 1884, 2000, and 2004.[36] This was the last election in which the Democrats won New Hampshire until 1936 and the last in which the Democrats won Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Maryland, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming until 1932. This would also be one of four times in which the winning presidential candidate lost his home state including 1844, 1968, and 2016. This election and the 1968 election are the only elections ever where the winning presidential and vice presidential candidates lost each of their home states. Wilson was the last Democrat to win an election without carrying Minnesota, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island (although he had previously won the latter two states in 1912). This was the first time since 1856 that Democrats won consecutive elections. 5.45% of Hughes' votes came from the eleven states of the former Confederacy, with him taking 24.89% of the vote in that region.[37]

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1916 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 28, 2005. Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005. Results by stateThe key state proved to be California, which Wilson won by only 3,800 votes out of nearly a million cast. If Hughes had carried California and its 13 electoral votes, he would have won the election. Although New Hampshire may not have been a deciding state in the election, the margin of victory for Wilson there was the second smallest ever recorded in an American presidential election at just 56 votes, behind Franklin Pierce's 25-vote victory in Delaware in 1852.[38][c] In some of the states carried by Wilson, particularly in the South, the popular vote margin was large. Wilson ran behind Hughes in New England, the Mid-Atlantic states, and in the East North Central section.[39] His lead was not great in the West North Central, but was very large in the West South Central and Mountain as well as in the East South Central and South Atlantic sections.[40] Half of Wilson's total vote was cast in the 18 states that he did not carry.

States that flipped from Democratic to Republican

States that flipped from Republican to DemocraticStates that flipped from Progressive to RepublicanStates that flipped from Progressive to DemocraticClose statesMargin of victory of less than 1% (52 electoral votes):

Margin of victory of less than 5% (77 electoral votes):

Margin of victory of between 5% and 10% (162 electoral votes):

Results by countyOf the 3,022 counties making returns, Wilson led in 2,039 counties (67.47%). Hughes managed to carry only 976 counties (32.30%), the smallest number in the Republican column in a two-party contest during the Fourth Party System. Two counties (0.07%) split evenly between Wilson and Hughes. Although the Progressive Party had no presidential candidate (just candidates for presidential electors who were unpledged for president), they carried five counties (0.17%), whilst nine counties – 0.30 percent and the same as in 1912 – inhabited either by Native Americans without citizenship or disenfranchised African Americans failed to return a single vote. Wilson carried 200 counties that had never voted Democratic in a two-party contest prior to that time.[42] Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Other)

Maps

AftermathThe gains made by Wilson in this election were a novel phenomenon under the Fourth Party System. This shift of votes led some to believe that the Democratic Party might have the position of decided advantage in the election of 1920.[42] See also

Notes

References

Bibliography

Primary sources

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to United States presidential election, 1916.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||