|

1832 United States presidential election

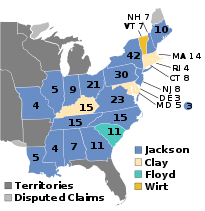

Presidential elections were held in the United States from November 2 to December 5, 1832. Incumbent president Andrew Jackson, candidate of the Democratic Party, defeated Henry Clay, candidate of the National Republican Party. The election saw the first use of the presidential nominating conventions, and the Democrats, National Republicans, and the Anti-Masonic Party all used conventions to select their candidates. Jackson won renomination with no opposition, and the 1832 Democratic National Convention replaced Vice President John C. Calhoun with Martin Van Buren. The National Republican Convention nominated a ticket led by Clay, a Kentuckian who had served as Secretary of State under President John Quincy Adams. The Anti-Masonic Party, one of the first major U.S. third parties, nominated former Attorney General William Wirt. Jackson faced heavy criticism for his actions in the Bank War, but remained popular among the general public. He won a majority of the popular vote and 219 of the 288 electoral votes, carrying most states outside New England. Clay won 37.4% of the popular vote and 49 electoral votes, while Wirt won 7.8% of the popular vote and carried the state of Vermont. Virginia Governor John Floyd, who had not actively campaigned, won South Carolina's electoral votes. After the election, members of the National Republican Party and the Anti-Masonic Party formed the Whig Party, which became the Democrats' primary opponent over the next two decades. NominationsWith the demise of the congressional nominating caucus in the election of 1824, the political system was left without an institutional method on the national level for determining presidential nominations. For this reason, the candidates of 1832 were chosen by national conventions. The first national convention was held by the Anti-Masonic Party in Baltimore, Maryland, in September 1831. The National Republican Party and the Democratic Party soon imitated them, also holding conventions in Baltimore, which would remain a favored venue for national political conventions for decades.[2] Democratic Party

President Jackson and Vice President Calhoun had a strained relationship for a number of reasons, most notably a difference in opinion about the Nullification Crisis and the involvement of Calhoun's wife Floride in the Eaton affair. As a result, Secretary of State Martin Van Buren and Secretary of War John H. Eaton resigned from office in April 1831, and Jackson requested the resignation of all other cabinet officers except one. Van Buren instigated the procedure as a means of removing Calhoun supporters from the Cabinet. Calhoun further aggravated Jackson in the summer of 1831 when he issued his "Fort Hill Letter," in which he outlined the constitutional basis for a state's ability to nullify an act of Congress. The final blow to the Jackson-Calhoun relationship came when Jackson nominated Van Buren to serve as Minister to Great Britain and the vote in the Senate ended in a tie, which Calhoun broke by voting against confirmation on January 25, 1832.[3] In January it was not clear who the Democrats' candidates would be in the election later that year. Jackson had already been nominated by several state legislatures, following the pattern in 1824 and 1828, but he worried that the various state parties would not unite on a vice-presidential nominee. As a result, the Democratic Party followed the pattern of the opposition and called a national convention.[4]

The 1832 Democratic National Convention, the Democratic Party's first, was held in the Athenaeum in Baltimore (the same venue as the two opposition parties) from May 21 to May 23, 1832. Several decisions were made at the convention. On the first day, a committee was appointed to provide a list of delegates from each state. This committee, later called the Credentials Committee, reported that all states were represented. Delegates were present from the District of Columbia, and on the first contested roll call vote in convention history, the convention voted 126–153 to deprive the District of Columbia of its voting rights in the convention. The Rules Committee gave a brief report that established several other customs. Each state was allotted as many votes as it had presidential electors; several states were overrepresented and many were underrepresented. Second, balloting was taken by states and not by individual delegates. Third, two-thirds of the delegates would have to support a candidate for nomination, a measure intended to reduce sectional strife. The fourth rule, which banned nomination speeches, was the only one the party quickly abandoned. No roll call vote was taken to nominate Jackson for a second term. Instead, the convention passed a resolution stating that "we most cordially concur in the repeated nominations which he has received in various parts of the union." Martin Van Buren was nominated for vice president on the first ballot, receiving 208 votes to 49 for Philip P. Barbour and 26 for Richard Mentor Johnson. Afterward, the convention approved an address to the nation and adjourned. Barbour DemocratsThe Barbour Democratic National Convention was held in June 1832 in Staunton, Virginia. Jackson was nominated for president and Philip P. Barbour for vice president. Barbour withdrew, but the ticket appeared on the ballot in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Virginia.[5] National Republican Party

Soon after the Anti-Masonic Party held its national convention, supporters of Henry Clay called a national convention of the National Republican Party. 18 of the 24 states sent delegations to the convention, which convened on December 12, 1831.[6] The convention was attended by 168 delegates from eighteen states although one-fourth of the delegates were late due to winter weather.[7] On the convention's fourth day, the roll call ballot for president took place. The chairman of the convention called the name of each delegate, who gave his vote orally. Clay received 155 votes, with delegate Frederick H. Shuman of North Carolina abstaining because he believed that Clay could not win and should wait until 1836. As additional delegates arrived, they were allowed to cast their votes for Clay, and by the end of the convention he had 167 votes to one abstention. A similar procedure was used for the vice-presidential ballot. Former Congressman John Sergeant of Pennsylvania was nominated with 64 votes to six abstentions. A prominent Philadelphia attorney with connections to the Second Bank of the United States and a reputation as an opponent of slavery, Sergeant gave the ticket geographical balance.[8]

Anti-Masonic Party

The first national nominating convention for a presidential candidate in American history was held by the Anti-Masonic Party in Baltimore, Maryland from September 26–28, 1831. The convention was attended by 116 delegates from thirteen states with Maryland being the furthest state in the South represented. The leaders of the party attempted to give the presidential nomination to Clay and Supreme Court Justice John McLean, but both declined.[7] Several prominent politicians were considered for the presidential nomination. Richard Rush would have been the nominee, but pointedly refused. As a result of this action, along with his softness toward Jackson, former President John Quincy Adams never forgave him. Adams was willing to run as the Anti-Masonic candidate, but the party leaders did not want to risk running someone so unpopular.[10] The delegates met behind closed doors for several days before the convention officially opened, making some initial decisions. Several unofficial presidential ballots and one official ballot were taken, in which William Wirt defeated Rush and John McLean for the nomination. Ironically, Wirt was a Mason and even defended the Order in a speech before the convention that nominated him.[11] Wirt hoped for an endorsement from the National Republicans. When the National Republican Party nominated Henry Clay, Wirt's position became awkward. He did not withdraw, even though he had no chance of being elected.[10] The convention was organized on September 26 and heard reports of its committees on the 27th. The 28th was spent on the official roll call for president and vice president. During the balloting, each delegate's name was called, after which that delegate placed a written ballot in a special box. Wirt was nominated for president with 108 votes to one for Rush and two abstentions. Amos Ellmaker was nominated for vice president with 108 votes to one for John C. Spencer (chairman of the convention) and two abstentions.[citation needed]

Nullifier PartyWhile the South Carolina state legislature remained nominally under Democratic control, it refused to support Jackson's reelection due to the ongoing Nullification Crisis, and instead opted to back a ticket proposed by the Nullifier Party led by John C. Calhoun. The Nullifiers were made up of former members of the Democratic-Republican Party who had largely supported Jackson at the previous election, but were much stauncher proponents of states' rights, which ultimately led them to repudiate Jackson during his first term. Calhoun himself declined to head the ticket, instead nominating Governor of Virginia John Floyd, who also opposed Jackson's stance on states' rights. Merchant and economist Henry Lee was nominated as Floyd's running mate.[13] Ultimately, Floyd's candidacy amounted to little more than a protest against Jackson, as his ticket did not run in any state outside of South Carolina. He nonetheless received all the state's electoral votes.[14] General election CampaignJackson rode into office in 1828 on the strength of a coalition that included southern opponents of the Tariff of 1828, western advocates of internal improvements, many former Democratic-Republicans, and some former Federalists. Henry Clay predicted this unwieldy marriage of disparate and in many cases hostile interests would soon collapse under the pressures of office.[15] Clay determined to split the Jacksonian party on the issue of the American System by engineering a confrontation over the Second Bank of the United States. He persuaded the president of the bank, Nicholas Biddle, to request recharter a full four years early in order to coincide with the presidential election. As expected, Jackson vetoed the recharter bill and issued a stinging veto message criticizing the bank's interference in national politics. Clay predicted the president's hostility to the nationalist economic program would prove unpopular with voters, particularly in Pennsylvania where the bank was headquartered, and hand the Anti-Jacksonians victory at the polls.[16] Simultaneously, Jackson faced defections from the southern wing of his party over the Nullification Crisis. These southerners objected strongly to the tariff and argued for the right of the states to nullify unfriendly federal laws, a position Jackson refused to endorse. Clay hoped to bring the disgruntled ex-Jacksonians into the fold, but his tactic of promoting the American System as the major issue of the campaign was ill-designed for this purpose. While some Southerners did favor the bank, they were unwilling to break publicly with Jackson on this issue, and Vice President Calhoun was overtly hostile to the American System by 1832. In South Carolina, the faction loyal to Calhoun nominated a slate of independent electors who voted for Governor John Floyd of Virginia. Elsewhere, dissident Southern Jacksonians protested the nomination of Martin Van Buren by supporting Philip P. Barbour for vice president but were unwilling to break with Jackson himself. As the Barbour movement suggests, Jackson's personal popularity worked against the growth of opposition politics in the South despite the growing dissatisfaction with the national administration.[17] Meanwhile, Jackson's northern opponents were hurt by the divided state of the opposition. The failure of Anti-Jacksonians to unite behind a single candidate for president alarmed leaders like William Henry Seward and Thurlow Weed, who worked feverishly to avoid a disastrous split in the opposition vote. In New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, Anti-Masons and National Republicans organized fusion tickets with electors pledged to support whichever candidate stood the best chance of defeating Jackson in the electoral college. Jackson carried all three states, however, along with their combined 93 electoral votes. His margin in Pennsylvania was much reduced from 1828, but still wider than the Democratic majority in the gubernatorial election held in October, due largely to the drop in support for the Anti-Masons. The Anti-Jacksonian "Union ticket" foreshadowed the merger of both parties with disaffected Southern Jacksonians in 1834 to form the Whig Party, which would constitute the major opposition to the Jacksonian Democrats for the remainder of the Second Party System.[18][19] While Clay hoped to alienate the different wings of the Democratic Party from each other by promoting the bank as an issue, his strategy backfired, as Jackson's veto message compellingly portrayed him as the defender of the common people against the furious assault of the financial interests. Events of the previous decade had not endeared the bank to working people, and they identified with Jackson's portrait of the "Monster Bank" as corrupt, self-interested, and destructive to democratic egalitarianism. Meanwhile, Clay's high-handed treatment of the Anti-Masons discouraged unity among Anti-Jacksonians, and the unpopularity of the National Republicans frustrated efforts to unite all opponents of the administration under a single roof.[20][21] Results20.6% of the voting age population and 56.7% of eligible voters participated in the election.[22] Jackson won the election in an electoral college landslide.[23] Jackson received 219 electoral votes, defeating Clay (49), Floyd (11), and Wirt (7) by a large margin.[24] Jackson's popularity with the American public and the vitality of the political movement with which he was associated is confirmed by the fact that no president was again able to secure a majority of the popular vote in two consecutive elections until Ulysses S. Grant in 1872. Only two other presidents from the Democratic party were ever able to replicate this feat: Franklin D. Roosevelt (for the first time in 1936) and Barack Obama (in 2012). Furthermore, no president succeeded in securing re-election again until Abraham Lincoln in 1864, and no Democrat would secure a second consecutive term until Woodrow Wilson in 1916.[25] As of 2024, Jackson was the second of eight presidential nominees to win a significant number of electoral votes in at least three elections, the others being Thomas Jefferson, Henry Clay, Grover Cleveland, William Jennings Bryan, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Richard Nixon, and Donald Trump. Of these, Jackson, Cleveland, and Roosevelt, also won the popular vote in at least three elections. Jackson was the second of only five presidents to win re-election with a smaller percentage of the popular vote than in prior elections, the other four are James Madison in 1812, Grover Cleveland in 1892, Franklin Roosevelt in 1940 and 1944 and Barack Obama in 2012.[26] Following the election and Clay's defeat, an Anti-Jackson coalition would be formed out of National Republicans, Anti-Masons, disaffected Jacksonians, and small remnants of the Federalist Party whose last political activity was with them a decade before. In the short term, it formed the Whig Party in a coalition against President Jackson and his reforms.[27]

(a) The popular vote figures exclude South Carolina where the Electors were chosen by the state legislature rather than by popular vote. Results by stateThe 1832 presidential election results are displayed in the maps below.[24][29]

States that flipped from National Republican to DemocraticStates that flipped from Democratic to National RepublicanStates that flipped from National Republican to Anti-MasonicStates that flipped from Democratic to NullifierClose statesStates where the margin of victory was under 1%:

States where the margin of victory was under 5%:

States where the margin of victory was under 10%:

Tipping point states:

Electoral College selection

See also

Notes

References

Bibliography

Primary sources

Websites

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to United States presidential election, 1832.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||