|

1892 United States presidential election

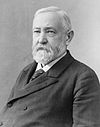

Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 8, 1892. In the fourth rematch in American history, the Democratic nominee, former president Grover Cleveland, defeated the incumbent Republican President Benjamin Harrison. Cleveland's victory made him the first president in American history to be elected to a non-consecutive second term, a feat not repeated until Donald Trump was elected in 2024. The 1892 election saw the incumbent White House party defeated in three consecutive elections, which did not occur again until 2024.[2] This was the first time a Republican president lost reelection. The Democrats did not win another presidential election until 1912. Harrison's loss was also the second time an elected president lost the popular vote twice, the first being John Quincy Adams in the 1820s. This feat was not repeated until Donald Trump lost the popular vote in 2016 and 2020 (but later won it in 2024).[3] Though some Republicans opposed Harrison's renomination, he defeated James G. Blaine and William McKinley on the first presidential ballot of the 1892 Republican National Convention. Cleveland defeated challenges by David B. Hill and Horace Boies on the first presidential ballot of the 1892 Democratic National Convention, becoming the fourth presidential candidate to be nominated for president in three elections, after Thomas Jefferson, Henry Clay, and Andrew Jackson. Groups from The Grange and the Knights of Labor joined to form a new party called the Populist Party. It had a ticket led by former congressman James B. Weaver of Iowa. The campaign centered mainly on economic issues, especially the protectionist 1890 McKinley Tariff. Cleveland ran on a platform of lowering the tariff and opposed the Republicans' 1890 voting rights proposal. He was also a proponent of the gold standard, while the Republicans and Populists both supported bimetallism. Cleveland swept the Solid South and won several important swing states, taking a majority of the electoral vote and a plurality of the popular vote. Weaver won 8.6% of the popular vote and carried several Western states, while John Bidwell of the Prohibition Party won 2.2% of the popular vote. NominationsDemocratic Party nomination

By the beginning of 1892, many Americans were ready to return to Cleveland's policies. Although he was the clear front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination, he was far from the universal choice of the party's supporters; many, such as the journalists Henry Watterson and Charles Anderson Dana, thought that if nominated, he would lose in November, but few could challenge him effectively. Though he had remained relatively quiet on the issue of silver versus gold, often deferring to bimetalism, Senate Democrats in January 1891 voted for free coinage of silver. Furious, he sent a letter to Ellery Anderson, who headed the New York Reform Club, to condemn the party's apparent drift towards inflation and agrarian control, the "dangerous and reckless experiment of free, unlimited coinage of silver at our mints." Advisors warned that such statements might alienate potential supporters in the South and West and risk his chances for the nomination, but Cleveland felt that being right on the issue was more important than the nomination. After making his position clear, he worked to focus his campaign on tariff reform, hoping that the silver issue would dissipate.[4] A challenger emerged in the form of David B. Hill, former governor of and incumbent senator from New York. In favor of bimetalism and tariff reform, Hill hoped to make inroads with Cleveland's supporters while appealing to those in the South and Midwest who were not keen on nominating Cleveland for a third consecutive time. Hill had unofficially begun to run for president as early as 1890, and even offered former Postmaster General Donald M. Dickinson his support for the vice-presidential nomination. But he was not able to escape his past association with Tammany Hall, and lack of confidence in his ability to defeat Cleveland for the nomination kept Hill from attaining the support he needed. By the time of the convention, Cleveland could count on the support of a majority of the state Democratic parties, though his native New York remained pledged to Hill.[5] In a narrow first-ballot victory, Cleveland received 617.33 votes, barely 10 more than needed, to 114 for Hill, 103 for Governor Horace Boies of Iowa, a populist and former Republican, and the rest scattered. Although the Cleveland forces preferred Isaac P. Gray of Indiana for vice president, Cleveland directed his own support to the convention favorite, Adlai E. Stevenson I of Illinois.[6] As a supporter of using paper greenbacks and free silver to inflate the currency and alleviate economic distress in rural districts, Stevenson balanced the ticket, as Cleveland supported hard money and the gold standard. At the same time, it was hoped that his nomination represented a promise not to ignore regulars, and so potentially get Hill and Tammany Hall to support the Democratic ticket to their fullest in the election.[7][8] Republican Party nomination

Harrison's administration was widely viewed as unsuccessful, and as a result, Thomas C. Platt (a political boss in New York) and other disaffected party leaders mounted a dump-Harrison movement coalescing around veteran candidate James G. Blaine from Maine, a favorite of Republican party regulars. Blaine had been the Republican nominee in 1884, losing to Cleveland. Privately, Harrison did not want to be renominated for the presidency, but he remained opposed to the nomination of Blaine, who he was convinced intended to run, and thought himself the only candidate capable of preventing that. But Blaine did not want another fight for the nomination and rematch against Cleveland in the general election. His health had begun to fail, and three of his children had recently died (Walker and Alice in 1890, and Emmons in 1892). Blaine refused to run actively, but the cryptic nature of his responses to a draft effort fueled speculation that he was not averse to such a movement. For his part, Harrison curtly demanded that he either renounce his supporters or resign as secretary of state, with Blaine doing the latter a scant three days before the National Convention. A boom began to build around the "draft Blaine" effort, with supporters hoping to cause a break toward their candidate.[9] Senator John Sherman of Ohio, who had been the leading candidate for the nomination at the 1888 Republican Convention before Harrison won it, was also brought up as a possible challenger. But like Blaine, he was averse to another bitter battle for the nomination and "like the rebels down South, [I] want to be let alone." This inevitably turned attention to Ohio Governor William McKinley, who was indecisive about his intentions despite his ill feeling toward Harrison and popularity among the Republican base. Although not averse to receiving the nomination, he did not expect to win it either. But should Blaine and Harrison fail to win the nomination after a number of ballots, he felt he could be brought forth as a harmony candidate. Despite the urging of Republican power broker Mark Hanna, McKinley did not put himself forward as a candidate, afraid of offending Harrison's and Blaine's supporters, while also feeling that the coming election would not favor the Republicans.[10] In any case, Harrison's forces had the nomination locked up by the time delegates met in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on June 7–10, 1892. Richard Thomas of Indiana delivered Harrison's nominating speech. Harrison was nominated on the first ballot with 535.17 votes to 182 for McKinley, 181.83 for Blaine, and the rest scattered. McKinley protested when the Ohio delegation threw its entire vote in his name, despite not being formally nominated, but Joseph B. Foraker, who headed the delegation, managed to silence him on a point of order.[11] With the ballots counted, many observers were surprised at the strength of the McKinley vote, which almost overtook Blaine's. Whitelaw Reid of New York, editor of the New York Tribune and recent United States Ambassador to France, was nominated for vice president. The incumbent vice president, Levi P. Morton, was supported by many at the convention, including Reid himself, but Morton did not wish to serve another term, as he was more interested in positioning himself to run for governor of New York in 1894.[11] Harrison did not want Morton on the ticket either.[citation needed] People's Party nomination

Populist candidates:

On May 19, 1891, the National Union Conference was held in Cincinnati, Ohio, to discuss the formation of a new political party. The conference held another meeting in St. Louis, Missouri, on February 22, 1892. Mary Elizabeth Lease, William A. Peffer, Jerry Simpson, and James B. Weaver toured the south in support of the agrarian third party. The Supreme Council of the Farmers' Alliance met in November and said it would support whatever the St. Louis convention did. 860 delegates, 246 from the Farmers' Alliance and 82 from the Knights of Labor, attended the convention. It adopted a declaration of union and independence, but did not form a new party due to opposition from Leonidas F. Livingston and southern southerners.[12] Another convention was held in Omaha, Nebraska, on July 4, with 1,366 in attendance despite initially planning for 1,776.[13] Alva Adams, Edward Bellamy, Robert Beverly, Marion Cannon, Ignatius L. Donnelly, James G. Field, Walter Q. Gresham, James H. Kyle, C. W. Macune, Mann Page, Leonidas L. Polk, Terence V. Powderly, Leland Stanford, William M. Stewart, Alson Streeter, Ben Terrell, Thomas E. Watson, Weaver, and Charles Van Wyck were speculated as possible presidential candidates.[14] Polk was the initial front-runner for the presidential nomination. He had been instrumental in the party's formation and greatly appealed to its agrarian base, but unexpectedly died in Washington, D.C., on June 11. Gresham, an appellate judge, had made a number of rulings against the railroads that made him a favorite of some farmer and labor groups, and it was felt that his rather dignified image would make the Populists appear as more than minor contenders. He had been considered for the Republican presidential nomination in 1884 and 1888. Both Democrats and Republicans feared his nomination for this reason, and while Gresham toyed with the idea, he ultimately was not ready to make a complete break with the two parties, declining petitions for his nomination up to and during the Populist Convention. Gresham later endorsed Grover Cleveland for president.[15][14] Weaver, the Greenback Party's 1880 presidential nominee,[16] was nominated for president on the first ballot, now lacking any serious opposition. While his nomination brought with it significant campaigning experience from over several decades, he also had a longer track record that Republicans and Democrats could criticize, and alienated many potential supporters in the South, having participated in Sherman's March to the Sea. James G. Field of Virginia was nominated for vice president in an attempt to rectify this problem while also attaining the regional balance often seen in Republican and Democratic tickets.[17]

Populist Convention Balloting by State Delegation The Populist platform called for nationalization of the telegraph, telephone, and railroads, free coinage of silver, a graduated income tax, and creation of postal savings banks. Prohibition Party nomination

Prohibition candidates:

Candidates gallery The sixth Prohibition Party National Convention assembled in Music Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio from June 29 to 30, 1892. There were 972 delegates present from all states except Louisiana and South Carolina.[21] Two major stories about the convention loomed before it assembled. In the first place, some members of the national committee sought to merge the Prohibition and Populist parties. While there appeared a likelihood that the merger would materialize, it was clear that it was not going to happen by the time that the convention convened. Secondly, the southern states sent a number of black delegates. Cincinnati hotels refused to serve meals to blacks and whites at the same time, and several hotels refused service to the black delegates altogether. John Bidwell, Gideon T. Stewart, and William Jennings Demorest sought the party's presidential nomination and a poll of delegates by the New York Herald showed Bidwell with the most support. John St. John, the party's 1884 nominee, nominated Bidwell.[22] Bidwell won the nomination on the first ballot. Prior to the convention, the race was thought to be close between Bidwell and Demorest, but the New York delegation became irritated with Demorest and voted for Bidwell 73–7. James B. Cranfill from Texas was nominated for vice-president on the first ballot with 417 votes to 351 for Joshua Levering from Maryland and 45 for others.[23]

Socialist Labor Party nominationThe Socialist Labor national convention was held in New York City on August 28, 1892.[25] Despite running on a platform that called for the abolition of the positions of president and vice-president, decided to nominate candidates for those positions. Simon Wing and Charles Matchett were selected as the party's presidential and vice presidential nominees.[26] They were on the ballot in five states: Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania.[27] Woman suffrageWyoming had become a state in 1890 and had included woman suffrage in its state constitution. Thus, Wyoming women were able to vote in the 1892 presidential election, the first time that any American women were able to do so.[28] A "national nominating convention of woman suffragists" met on September 21, 1892, and nominated notorious suffrage and former free-love advocate (at the time, "free love" meant the freedom to marry, divorce and bear children without social restriction or government interference[29]) Victoria Woodhull for president and Marietta Stow for vice president.[30] Both had been nominated for these positions before, Woodhull in 1872[31] and Stow in 1884. Both had been nominated by the National Equal Rights Party, which did not nominate a ballot in 1892; instead, the woman suffrage nominating convention, headed by Anna M. Parker and consisting of 50 delegates from 29 states, stepped in.[30] Women in most states were not yet allowed to vote in 1892, but the convention's platform urged "election officers throughout the country to allow them to cast a ballot this fall."[32] They were not successful in this, and it was almost 30 more years until the Nineteenth Amendment prohibited discrimination in voting on the basis of sex. General electionCampaign On July 27, James S. Clarkson, who opposed Harrison's renomination, was replaced as chair of the Republican National Committee by William James Campbell. Campbell resigned on July 6, and Thomas H. Carter was selected to replace him on July 16.[33] It was believed that Calvin S. Brice, the current chair of the Democratic National Committee, would seek reelection, but he declined and William F. Harrity was selected without opposition. Donald M. Dickinson was selected to chair the DNC's campaign committee.[34] Campbell, J.N. Huston, E. Rosewater, R.G. Evans, and Henry Clay Payne managed Harrison's campaign in the west. William Brookfield and Charles W. Hacket led his campaign in New York.[35] Edward Murphy and William F. Sheehan were selected to lead Cleveland's campaign in New York despite Cleveland's opposition. Murphy and Sheehan were opponents of Cleveland, but William Collins Whitney argued that they should be given the positions for party unity.[36] The Republicans launched their national campaign on June 21, in New York City at Carnegie Hall. The Democrats launched their campaign at two meetings. Tammany Hall held one on July 4, and the Democrats held another one at Madison Square Garden on July 20.[37] The Prohibitionists launched their campaign in San Francisco on August 4.[38] The tariff issue dominated this rather lackluster campaign. Harrison defended the protectionist McKinley Tariff passed during his term. For his part, Cleveland assured voters that he opposed absolute free trade and would continue his campaign for a reduction in the tariff. He also denounced the Lodge Bill, a voting rights bill that sought to protect the rights of African American voters in the South.[39] Harrison initially planned on conducting a speaking tour in New York, but chose to care for his ill wife Caroline Harrison. Reid conducted tours of Illinois, Ohio, and New York. McKinley extensively campaigned for Harrison from Iowa to Maine. Stevenson launched his campaign activities in his hometown of Bloomington, Illinois, and traveled across Delaware, North Carolina, and Virginia for sixteen days.[40] Weaver started campaigning in July and conducted a tour of the western and southern United States.[41] The campaign took a somber turn when, in October, Caroline died. Despite the ill health that had plagued Mrs. Harrison since her youth and had worsened in the last decade, she often accompanied Mr. Harrison on official travels. On one such trip, to California in the spring of 1891, she caught a cold. It quickly deepened into her chest, and she was eventually diagnosed with tuberculosis. A summer in the Adirondack Mountains failed to restore her to health. An invalid the last six months of her life, she died in the White House on October 25, 1892, just two weeks before the national election. As a result, all of the candidates ceased campaigning. FusionThe Democrats and Populists conducted a partial fusion campaign in Oregon by having Democratic elector Robert A. Miller drop out, while the Democratic Party of Oregon endorsed Populist elector I. Nathan Pierce in his place. The Democrats believed that the Populists would do the same for two electors, but the Populists refused.[42] The Minnesota Democratic Party initially announced that it would not conduct a fusion campaign, but later withdrew four of its electors in favor of Populist electors.[43] The Nevada Democratic Party passed a resolution at its convention stating that it would not support the party's presidential nominee if they did not support free silver. A majority of the party supported Weaver while a minority ran electors pledged to Cleveland. The Silver Party voted to have its Nevada presidential electors support the Populists. The Nevada Republican Party held a convention to select its presidential electors, but party chair Enoch Strother and 49 delegates left the convention after a caucus showed free silver delegates held a majority. These delegates nominated electors pledged to Harrison while the 85 silver delegates endorsed the Silver Party's electors.[44] The Wyoming Democratic Party endorsed the Populist electors in exchange for the Populists supporting the Democratic state candidates. The North Dakota Democratic Party endorsed the Independent Party's electors, who were pledged to Weaver, in exchange for the Independent Party supporting its state candidates. The Kansas Democratic Party made an agreement with the Populists in which the Democrats would run candidates for some state and federal offices while leaving the rest, including presidential electors, to the Populists.[45] The Republican Party of Louisiana agreed to divide the electors between five for Harrison and three for Weaver. The Republican Party of Florida did not nominate any electors and its members supported Weaver.[46] Results 34.9% of the voting age population and 78.3% of eligible voters participated in the election.[47] The margin in the popular vote for Cleveland was 400,000, the largest since Grant's re-election in 1872.[48] The Democrats won the presidency and both houses of Congress for the first time since 1856. President Harrison's re-election bid was a decisive loss in both the popular and electoral count, unlike President Cleveland's re-election bid four years earlier, in which he won the popular vote, but lost the electoral vote. This was the second time that a party lost re-election after a single four-year term, which would not occur again until 1980, and for Republicans until 2020. At the county level, Cleveland fared much better than Harrison. The Republicans' vote was not nearly as widespread as the Democrats'. In 1892, it was still a sectionally based party mainly situated in the East, Midwest, and West and was barely visible south of the Mason–Dixon line. In the South, the party was holding on in only a few counties. In East Tennessee and tidewater Virginia, the vote at the county level showed some strength, but it barely existed in Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas.[49] Additionally, Cleveland was the third of only five presidents to win re-election with a smaller percentage of the popular vote than in prior elections. The other four are Andrew Jackson in 1832, James Madison in 1812, Franklin Roosevelt in 1940 and 1944, and Barack Obama in 2012. As of 2024, Cleveland was the fourth of eight presidential nominees to win a significant number of electoral votes in at least three elections, the others being Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, William Jennings Bryan, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Richard Nixon, and Donald Trump. Of these, Jackson, Cleveland, and Roosevelt also won the popular vote in at least three elections. Jefferson, Cleveland, Roosevelt, and Trump were also their respective party's nominees for three consecutive elections. In a continuation of its collapse there during the 1890 congressional elections, the Republican Party even struggled in its Midwestern strongholds, where general electoral troubles from economic woes were acutely exacerbated by the promotion of temperance laws and, in Wisconsin and Illinois, the aggressive support of state politicians for English-only compulsory education laws. Such policies, which particularly in the case of the latter were associated with an upwelling of nativist and anti-Catholic attitudes amongst their supporters, resulted in the defection of large sections of immigrant communities, especially Germans, to the Democratic Party. Cleveland carried Wisconsin and Illinois with their 36 combined electoral votes, a Democratic victory not seen in those states since 1852[50] and 1856[51] respectively, and which would not be repeated until Woodrow Wilson's election in 1912. While not as dramatic a loss as in 1890, it would take until the next election cycle for more moderate Republican leaders to pick up the pieces left by the reformist crusaders and bring alienated immigrants back to the fold.[52] Of the 2,683 counties making returns, Cleveland won in 1,389 (51.77%), Harrison carried 1,017 (37.91%), while Weaver placed first in 276 (10.29%). One county (0.04%) split evenly between Cleveland and Harrison. Populist James B. Weaver, calling for free coinage of silver and an inflationary monetary policy, received such strong support in the West that he became the only third-party nominee between 1860 and 1912 to carry a single state. The Democratic Party did not have a presidential ticket on the ballot in the states of Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, North Dakota, or Wyoming, and Weaver won the first four of these states.[53] Weaver also performed well in the South as he won counties in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Texas. Populists did best in Alabama, where electoral chicanery probably carried the day for the Democrats.[48] The Prohibition ticket received 270,879 votes, or 2.2% nationwide. It was the largest total vote and the highest percentage of the vote received by any Prohibition presidential candidate.[54] Wyoming, having attained statehood two years earlier, became the first state to allow women to vote in a presidential election since 1804. (Propertied unmarried women in New Jersey had the right to vote under the state's original constitution, but this was rescinded in 1807.) Wyoming was also one of six states (along with North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Washington, and Idaho) participating in their first presidential election. This was the most new states voting since the first election. The 0.09% difference between the tipping point state (Illinois) and the national popular vote is tied with 1932 for the smallest in history. The election witnessed many states splitting their electoral votes. Electors from the state of Michigan were selected using the congressional district method (the winner in each congressional district wins one electoral vote, the winner of the state wins two electoral votes). This resulted in a split between the Republican and Democratic electors: nine for Harrison and five for Cleveland.[55] In California, the direct election of presidential electors combined with the close race resulted in a split between the Republican and Democratic electors: eight for Cleveland and one for Harrison.[55] In Ohio, the direct election of presidential electors combined with the close race resulted in a split between the Republican and Democratic electors: 22 for Harrison and one for Cleveland.[55] Cleveland was the first Democratic presidential nominee to win Illinois since 1856 and Wisconsin since 1852.[56] 10.45% of Harrison's votes came from the 11 states of the former Confederacy. He took 25.34% of the vote in that region to Weaver's 15.87%.[57] 61 of 67 counties in New England, where Connecticut was the only state won by Cleveland, supported Harrison. Weaver placed fourth, behind the Prohibitionists, in every New England state. 3% of the vote in New England went to third parties, with the Prohibitionists accounting for 70% of it. 343 of the counties in the upper south supported Cleveland, 165 supported Harrison, and 2 supported Weaver. 619 counties in the deep south supported Cleveland, 47 supported Weaver, 32 supported Harrison, and 8 supported fusion electors.[58] Harrison won 226 counties, Cleveland won 206, and Weaver won 1 in the midwestern states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin.[59]

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1892 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 27, 2005. Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005. Geography of results

Cartographic gallery

Results by stateSource: Data from Walter Dean Burnham, Presidential ballots, 1836–1892 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1955) pp 247–57.[60]

States that flipped from Republican to DemocraticStates that flipped from Republican to PopulistClose statesMargin of victory less than 1% (35 electoral votes):

Margin of victory between 1% and 5% (158 electoral votes):

Margin of victory between 5% and 10% (101 electoral votes):

See also

References

Works cited

Further reading

Primary sources

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to United States presidential election, 1892.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||