|

1912 United States presidential election

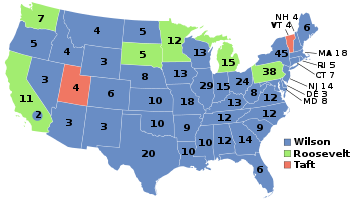

Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 5, 1912. Democratic governor Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey unseated incumbent Republican president William Howard Taft while defeating former president Theodore Roosevelt (who ran under the banner of the new Progressive/"Bull Moose" Party) and Socialist Party nominee Eugene V. Debs.[1] Roosevelt served as president from 1901 to 1909 as a Republican, and Taft succeeded him with his support. Taft's conservatism angered Roosevelt, so he challenged Taft for the party nomination at the 1912 Republican National Convention. When Taft and his conservative allies narrowly prevailed, Roosevelt rallied his progressive supporters and launched a third-party bid. At the Democratic Convention, Wilson won the presidential nomination on the 46th ballot, defeating Speaker of the House Champ Clark and several other candidates with the support of William Jennings Bryan and other progressive Democrats. The Socialist Party renominated its perennial standard-bearer, Eugene V. Debs. The general election was bitterly contested by Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft and Debs. Roosevelt's "New Nationalism" platform called for social insurance programs, reduction to an eight-hour workday, and robust federal regulation of the economy. Wilson's "New Freedom" platform called for tariff reduction, banking reform, and new antitrust regulation. Incumbent Taft conducted a subdued campaign based on his platform of "progressive conservatism". Debs, who was attempting to gain widespread support for his socialist policies, claimed that Wilson, Roosevelt and Taft were all financed by different factions within the capitalist trusts, and that Roosevelt in particular was a demagogue using socialistic language in order to divert socialist policies up safe channels for the capitalist establishment. The Republican split enabled Wilson to win 40 states and a landslide victory in the electoral college with just 41.8% of the popular vote, the lowest vote share for a victorious presidential candidate since 1860. Wilson was the first Democrat to win a presidential election since 1892 as well as the first presidential candidate to receive over 400 electoral votes in a presidential election. Roosevelt finished second with 88 electoral votes and 27% of the popular vote. Taft carried 23% of the national vote and won two states, Vermont and Utah. Debs, the fourth-place finisher, won no electoral votes but received 6% of the popular vote, which remains the highest percentage of the vote ever won by a socialist candidate in the history of US presidential elections. This is the most recent presidential election, and the first since 1876, in which the Democratic ticket has consisted of sitting governors. BackgroundRepublican president Theodore Roosevelt had declined to run for re-election in 1908 in fulfillment of a pledge to the American people not to seek a third term.[a] Roosevelt had tapped Secretary of War William Howard Taft to become his successor, and Taft defeated William Jennings Bryan in the 1908 general election. Republican Party split During Taft's administration, a rift developed between Roosevelt and Taft, and they became the leaders of the Republican Party's two wings: progressives led by Roosevelt and conservatives led by Taft.[2] Progressives favored labor restrictions protecting women and children, promoted ecological conservation, and were more sympathetic toward labor unions. They also favored the popular election of federal and state judges over appointment by the president or governors. Conservatives supported high tariffs to encourage domestic production, but favored business leaders over labor unions and were generally opposed to the popular election of judges. Taft's policiesCracks in the party began to show when Taft supported the Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act in 1909.[3] The Act favored the industrial Northeast and angered the Northwest and South, where demand was strong for tariff reductions.[4] Early in his term, President Taft had promised to stand for a lower tariff bill, but protectionism had been a major policy of the Republican Party since its founding.[5] Taft also fought against Roosevelt's antitrust policy.[6] Roosevelt distinguished "good trusts" from "bad trusts", for which he had been lambasted.[7] Taft argued that all monopolies must be broken up. Taft also fired popular conservationist Gifford Pinchot as head of the Bureau of Forestry in 1910.[8] By 1910, the split within the party was deep, and Roosevelt and Taft turned against one another despite their personal friendship. In that summer Roosevelt began a national speaking tour, during which he outlined his progressive philosophy and the New Nationalist platform, which he introduced in a speech in Osawatomie, Kansas, on August 31.[9] Court power and judicial recallAnother source of tension involved the authority of the nation's courts, especially the Supreme Court. As early as 1910, Roosevelt had begun criticizing certain court decisions, such as Lochner v. New York (1905), and those jurists whom he dubbed "fossilized judges." He believed that the Supreme Court was interpreting the due process clause of the 14th Amendment and the doctrine of "freedom of contract" to forestall necessary reform legislation, such as the limiting of work hours. He, as well as more populist progressives like William Jennings Bryan in the Democratic Party, came out in favor of an amendment to allow the recall of judges and, possibly, judicial decisions. This outraged Taft (a former judge and future Supreme Court Chief Justice) and other constitutional conservatives, like Elihu Root and Alton B. Parker. Taft considered Roosevelt a danger to constitutional government and resolved to resist his eventual challenge for the Republican nomination.[10] Roosevelt emboldenedIn the 1910 midterm elections, the Republicans lost 57 seats in the House of Representatives as the Democrats gained a majority for the first time since 1894. These results were a large defeat for the conservative wing of the party.[11] James E. Campbell writes that one cause may have been a large number of progressive voters choosing third-party candidates over conservative Republicans.[12] Roosevelt continued to reject calls to run for president into 1911. In a January letter to newspaper editor William Allen White, he wrote, "I do not think there is one chance in a thousand that it will ever be wise to have me nominated."[13] However, speculation continued, further harming Roosevelt and Taft's relationship. After months of continually increasing support, Roosevelt changed his position, writing to journalist Henry Beach Needham in January 1912 that if the nomination "comes to me as a genuine public movement of course I will accept."[14] NominationsRepublican Party nomination

Other major candidates

Delegate selectionFor the first time, many convention delegates were elected in presidential preference primaries. Progressive Republicans advocated primary elections as a way of breaking the control of political parties by bosses. Altogether, twelve states held Republican primaries. Senator Robert "Fighting Bob" La Follette won two of the first four primaries (North Dakota and his home state of Wisconsin), but Taft won a major victory in Roosevelt's home state of New York and continued to rack up delegates in more conservative, traditional state conventions. Beginning with a runaway victory in Illinois on April 9, Roosevelt won nine of the last ten presidential primaries (including Taft's home state of Ohio), losing only Massachusetts.[15] Taft also had support from the bulk of the Southern Republican organizations. Delegates from the former Confederate states supported Taft by a 5 to 1 margin. These states had voted solidly Democratic in every presidential election since 1880, and Roosevelt objected that they were given one-quarter of the delegates when they would contribute nothing to a Republican victory. ConventionFor the Republican National Convention, held June 18-22 in Chicago, 388 delegates were selected through the primaries and Roosevelt won 281 delegates, Taft received 71 delegates, and La Follette received 36 delegates. However, Taft had a 566–466 margin, placing him over the 540 needed for nomination, with the delegations selected at state conventions. Roosevelt accused the Taft faction of having over 200 fraudulently selected delegates. However, the Republican National Committee ruled in favor of Taft for 233 of the delegate cases while 6 were in favor of Roosevelt. The committee reinvestigated the 92 of the contested delegates and ruled in favor of Taft for all of them.[16][17] Roosevelt supporters criticized the large amount of delegates coming from areas the Republicans would not win, with over 200 delegates coming from areas that had not been won by a Republican since the Compromise of 1877, or the four delegates that came from the territories which didn't vote in the general election. However, Roosevelt had rejected an attempt to abolish delegations from the south at the 1908 Republican National Convention due to him needing them for Taft's nomination.[16] Herbert S. Hadley served as Roosevelt's floor manager at the convention. Hadley made a motion for 74 of Taft's delegates to be replaced by 72 delegates after the reading of the convention call, but his motion was ruled out of order. Elihu Root, a supporter of Taft, was selected to chair the convention after winning 558 votes against McGovern's 501 votes. Root was accused of having won through the rotten boroughs of the southern delegations as every northern state, except for four, voted for McGovern.[16] In his closing speech, Root reiterated the party's support of "constitutional checks and limitations" by quoting figures like Alexander Hamilton, John Marshall, and Abraham Lincoln, effectively rebuking Roosevelt's support of the judicial recall and identifying the GOP with constitutional conservatism.[18] Roosevelt broke with tradition and attended the convention, where he was welcomed with great support from voters.[19] Despite Roosevelt's presence in Chicago and his attempts to disqualify Taft supporters, the incumbent ticket of Taft and James S. Sherman was renominated on the first ballot.[20] Sherman was the first sitting vice president re-nominated since John C. Calhoun in 1828. After losing the vote, Roosevelt announced the formation of a new party dedicated "to the service of all the people."[21] This would later come to be known as the Progressive Party. Roosevelt announced that his party would hold its convention in Chicago and that he would accept their nomination if offered.[21] Meanwhile, Taft decided not to campaign before the election beyond his acceptance speech on August 1.[22] Warren G. Harding presented Taft's name for the nomination. Taft won the nomination while 344 of Roosevelt's delegates abstained from the vote. Henry Justin Allen read a speech from Roosevelt in which he criticized the process and stated that delegates had been stolen from his in order to secure Taft's nomination.[16]

Democratic Party nomination

Other major candidates

In early 1912, it was widely believed that three-time Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan would make a fourth attempt to earn the party's nomination, and would likely not have difficulty in earning it. However, Bryan announced several months before the convention that he was not interested in another run for the White House. Though still seen by many as the Democrats' ideological leader, power shifts within the party in the wake of their success at the 1910 mid-term elections meant that Bryan could no longer be guaranteed the two-thirds majority needed to earn the nomination. Bryan privately conceded that his three presidential runs having all ended in decisive losses, firstly to William McKinley, and then to Taft, would seriously handicap his credibility as a candidate, even if the 1904 election, the only one of the previous four in which Bryan was not the Democratic candidate, had resulted in an even more lop-sided defeat for the party. However, Bryan still had enough followers in the party that he was in a strong position to be the kingmaker at the convention. The Democratic National Convention was held in Baltimore from June 25 to July 2. Initially, the front-runner was Speaker of the House Champ Clark of Missouri. Though Clark received the most votes on early ballots, he was unable to get the two-thirds majority required to win. Clark's chances were hurt when Tammany Hall, the powerful New York City Democratic political machine, threw its support behind him. The Tammany endorsement caused Bryan to turn against Clark, whom he decried as the candidate of Wall Street, and shift his support to Woodrow Wilson, the reformist Governor of New Jersey. Wilson had consistently finished second in balloting, and nearly gave up hope and almost freed his delegates to vote for another candidate. Instead, Bryan's defection from Clark to Wilson led many other delegates to do the same. Wilson gradually gained strength while Clark's support dwindled, and Wilson finally received the nomination on the 46th ballot. Thomas R. Marshall, the governor of Indiana who had swung Indiana's votes to Wilson, was named Wilson's running mate.

Progressive Party nomination

Taft had won the Republican nomination while 344 of Roosevelt's delegates abstained from the vote. Later that day supporters of Roosevelt met in the Chicago Orchestra Hall and nominated him as an independent candidate for president which Roosevelt accepted although he requested a formal convention. Roosevelt initially considered not running as a third-party candidate until George Walbridge Perkins and Frank Munsey offered their financial support. Roosevelt and his supporters formed the Progressive Party at a convention, temporarily chaired by Senator Albert J. Beveridge, on August 5, and Hiram Johnson was selected as his vice-presidential running mate. Ben B. Lindsey and John M. Parker had been considered for the presidential nomination, but Parker and Lindsey instead both nominated Johnson for the position.[16] The Progressives promised to increase federal regulation and protect the welfare of ordinary people. At the convention, Perkins blocked an antitrust plank, shocking reformers who thought of Roosevelt as a true trust-buster.[citation needed] The delegates to the convention sang the hymn "Onward, Christian Soldiers" as their anthem. In his acceptance speech, Roosevelt compared the coming presidential campaign to the Battle of Armageddon and stated that the Progressives were going to "battle for the Lord."[26] Socialist Party nomination

Socialist candidates:

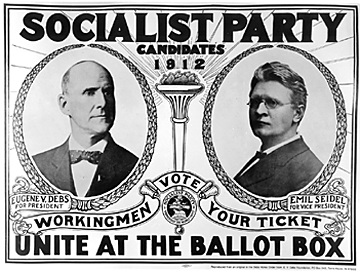

Members of the Socialist Party of America had won in multiple elections between the 1908 and 1912 presidential elections with Emil Seidel being elected as the mayor of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Victor L. Berger was elected to the United States House of Representatives. The party claimed that it had 435 members elected to office by 1911, and over one thousand by 1912.[27] Dan Hogan put Debs name up for the presidential nomination. Debs won the presidential nomination, although he had supported giving the nomination to the Appeal to Reason's editor Fred Warren, with 165 votes while Seidel received 56 votes and Charles Edward Russell received 54 votes. Seidel was given the vice-presidential nomination against Russell and Hogan.[28][29][30] After the presidential ballot Seidel and Russell proposed a motion to make Debs' nomination unanimous and it was accepted. Hogan and Slayton proposed to make the nomination of Seidel unanimous after the vice-presidential selection and it was accepted. Otto Branstetter, Berger, and Carl D. Thompson, who were serving as delegates, voted for Seidel during the presidential balloting. Morris Hillquit, Meyer London, and John Spargo, who were serving as delegates, supported Russell during the presidential balloting. Hogan, a delegate from Arkansas, had supported Debs during the presidential balloting.[31] J. Mahlon Barnes, who had managed Debs' campaign in the 1908 election, also managed the campaign in 1912. The Socialists predicted that they would receive over two million votes and have twelve members elected to Congress, but Debs only received 897,011 votes and Berger lost reelection. Debs received his largest number of votes from Ohio while his best percentage was in Nevada. The largest percentage gain since the 1908 presidential election was in West Virginia where their vote total increased by over 300%. George Brinton McClellan Harvey stated that had Roosevelt not run then Debs would have gained an additional half a million votes.[27] The number of Socialists in the state legislatures increased from twenty to twenty-one.[32]

General electionRoosevelt conducted a vigorous national campaign for the Progressive Party, denouncing the way the Republican nomination had been "stolen". He bundled together his reforms under the rubric of "The New Nationalism" and stumped the country for a strong federal role in regulating the economy and chastising bad corporations.[citation needed] Roosevelt rallied progressives with speeches denouncing the political establishment. He promised "an expert tariff commission, wholly removed from the possibility of political pressure or of improper business influence."[33] Wilson supported a policy called "The New Freedom". This policy was based mostly on individualism instead of a strong government.[citation needed]  Wilson opposed Roosevelt's proposal to establish a powerful state bureaucracy charged with regulating large corporations, with Wilson instead favoring the break-up of large corporations in order to create a level economic playing field. Though Wilson's rhetoric paid homage to the traditional Democratic Party skepticisms of government and "collectivism", after his election win Wilson would embrace some of the progressive reforms which Roosevelt had campaigned on.  Taft campaigned quietly and spoke of the need for judges to be more powerful than elected officials. The departure of the progressives left the Republican Party firmly controlled by the conservative wing. Much of the Republican effort was designed to discredit Roosevelt as a dangerous radical, but this had little effect.[citation needed] Many of the nation's pro-Republican newspapers depicted Roosevelt as an egotist running only to spoil Taft's chances and feed his vanity.[citation needed] The Socialists had little funding compared to the Republican, Democratic and Progressive campaigns. Debs' campaign spent only $66,000, mostly on 3.5 million leaflets and travel to locally organized rallies. Debs' biggest event was a speech to 15,000 supporters in New York City. The crowd sang "La Marseillaise" and "The Internationale." Debs's running mate Emil Seidel boasted:

Debs claimed that there was no hope under the present decaying capitalist system, and that the worker who votes the Republican or Democratic ticket does worse than throw away his vote, as he is a deserter of his class and becomes his own worst enemy. Debs insisted that Democrats, Progressives, and Republicans alike were financed by different factions within the capitalist trusts, and that only the Socialists represented labor. Debs condemned "Injunction Bill Taft" and condemned Roosevelt for stealing his socialist clothes with the intent to make socialist policies "safer" for the establishment. At a campaign speech in Philadelphia on September 28, 1912, Debs said of Roosevelt:

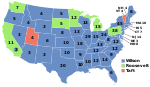

Attempted assassination of Theodore RooseveltAt a campaign stop in Milwaukee on October 14, John Schrank, a saloonkeeper from New York, shot Roosevelt in the chest. The bullet penetrated his steel eyeglass case and a 50-page single-folded copy of his speech Progressive Cause Greater Than Any Individual and became lodged in his chest. Schrank was immediately disarmed and captured.[35] Schrank had been stalking Roosevelt. He was suffering from delusion and said the ghost of President McKinley ordered him to kill Roosevelt to prevent a third term.[36] Roosevelt shouted for Schrank to remain unharmed and assured the crowd he was all right, then ordered police to take charge of Schrank and ensure no violence was done to him.[37] Roosevelt, an experienced hunter and anatomist, correctly concluded that since he was not coughing blood, the bullet had not reached his lung. He declined suggestions to go to the hospital and instead delivered his scheduled speech with blood seeping into his shirt.[38] His opening comments to the gathered crowd were, "Ladies and gentlemen, I don't know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot, but it takes more than that to kill a bull moose." He spoke for 90 minutes before completing his speech and accepting medical attention.[39][40] Afterward, probes and an x-ray showed that the bullet had lodged in Roosevelt's chest muscle, but did not penetrate the pleura. Doctors concluded that it would be less dangerous to leave it in place than to attempt to remove it, and Roosevelt carried the bullet with him for the rest of his life.[41][42] Taft was not campaigning and focused on his presidential duties. Wilson briefly suspended his campaigning. By October 17, Wilson was back on the campaign trail but avoided any criticism of Roosevelt or his party.[43] Roosevelt spent two weeks recuperating before returning to the campaign trail with a major speech on October 30, designed to reassure his supporters he was strong enough for the presidency.[44] Death of Vice President ShermanOn October 30, 1912, Vice President James S. Sherman died of nephritis, leaving Taft without a running mate less than a week before the election. Nicholas Murray Butler, president of Columbia University, was quickly chosen to replace Sherman on the Republican ticket.[45] Results27.9% of the voting age population and 59% of eligible voters participated in the election.[46] Wilson captured the presidency handily by carrying a record 40 states. As of 2024[update], this is the only presidential election since 1860 in which 4 candidates received more than 5% of the popular vote and a third-party candidate outperformed a major party candidate in the general election.[citation needed] This election saw the lowest turnout among eligible voters since the 1836 presidential election, falling 20 points short of the turnout in the 1896 election.[citation needed] The implementation of Jim Crow laws after the Reconstruction Era significantly reduced Black voter turnout.[47] Wilson won the presidency with a lower percentage of the popular vote than any candidate since Abraham Lincoln in 1860. Taft's result remains the worst performance for any incumbent president, both in terms of electoral votes (8) and share of popular votes (23.17%). His 8 electoral votes remain the fewest by a Republican and by any major-party candidate, matched by Alf Landon's 1936 campaign. His 23.17% of the popular vote is the lowest ever for a Republican or any major party nominee. This was the first time since 1852 that Iowa, Maine, New Hampshire, Ohio, and Rhode Island voted for a Democrat, and the first time in history that Massachusetts voted Democratic. Democrats would not win Maine again until 1964, Connecticut and Delaware until 1936, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, West Virginia, and Wisconsin until 1932, and Massachusetts and Rhode Island until 1928. Additionally, it was the last time until 1932 that the Republicans failed to win Michigan, Minnesota and South Dakota. This is one of two times since 1852 that Maine and Vermont did not support the same party (the other being in 1968). Theodore Roosevelt's 88 electoral votes and 27.4% of the popular vote are the highest won by a third party in a presidential election.[48] Wilson's raw vote total and percentage was less than William Jennings Bryan's total in any of his three campaigns.[49] In only two regions, New England and the Pacific, was Wilson's vote greater than the greatest Bryan vote.[50] The 1912 election was the first to include all 48 of the current contiguous United States. Only 12 of the 48 states saw a candidate win with a majority of the popular vote. Wilson won a majority in the 11 former Confederate states. Only South Dakota, where Taft did not appear on the ballot, gave Roosevelt a majority. Taft won only two states, Vermont and Utah, each with a plurality.[49] This is the only time in American history that three people who at some point served as president ran in the same election.

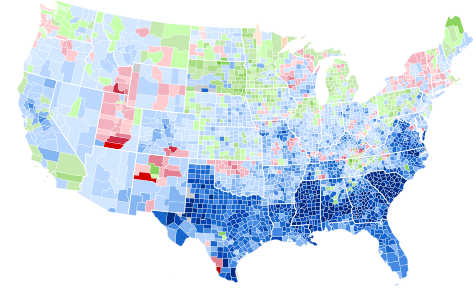

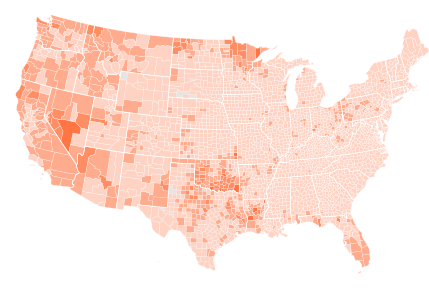

Wilson finished 1st in 40 states. He finished 2nd behind Roosevelt in 5 states, and 2nd behind Taft only in Utah. He finished 3rd in 2 states, in Michigan where Roosevelt finished 1st and Taft finished 2nd, and in Vermont where Taft finished 1st and Roosevelt finished 2nd. Roosevelt would win the most electoral votes out of any third-party candidate in American history, finishing 1st in 6 states.[51] He finished 2nd in 24 states, behind Wilson in 23, and behind Taft in Vermont. He finished 3rd in 17 states. In 15 of those, Wilson finished 1st and Taft finished 2nd. In the other two, Taft finished 1st and Wilson finished 2nd in Utah, while Wilson finished 1st and Debs finished 2nd in Florida. Roosevelt was not on the ballot in Oklahoma. Taft finished 1st in Vermont and Utah. He finished 2nd in 18 states, behind Wilson in 17 of those. The one exception was Michigan where Taft finished 2nd behind Roosevelt. He finished 3rd in 21 states. In 18 of those, Wilson finished 1st and Roosevelt finished 2nd. In the other 3, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Washington, Roosevelt finished 1st and Wilson finished 2nd. Taft also finished 4th in 5 states. In 4 of those, the top 3 in order were Wilson-Roosevelt-Debs. In Florida, Wilson finished 1st, Debs finished 2nd, and Roosevelt finished 3rd. While not on the ballot in California, Taft received 3,914 write-in votes in the state, placing him 5th, behind Roosevelt, Wilson, Debs, and Chafin. Taft was not on the ballot at all in South Dakota, not even as a write-in option. Debs finished 2nd in Florida behind Wilson. He finished 3rd in 7 states. In Nevada, Arizona, Louisiana and Mississippi, Wilson finished 1st, Roosevelt finished 2nd, Debs finished 3rd and Taft finished 4th. The other 3 states where Debs finished 3rd were Oklahoma, where Roosevelt was not on the ballot; South Dakota, where Taft was not on the ballot; and California, where Taft was not on the ballot, but received write-in votes, causing Taft to finish 5th in California. Debs finished 4th in 38 states. Debs was beaten by Chafin in two states, Vermont and Delaware, with Debs finishing 5th in both states. Chafin finished last in 18 states. The states where Chafin avoided finishing last were 19 of the 20 states where Reimer was on the ballot – Reimer finished last in all 20 states that he contested – as well as Vermont and Delaware, where Chafin managed to force Debs into last place. The other state where Chafin avoided last place was California, where Taft was only a write-in candidate and finished last. Reimer was not on the ballot in 28 states, while Chafin was not on the ballot in 8 states. Only in Utah was Reimer on the ballot but Chafin was not. 5.44% of Taft's votes came from the eleven states of the former Confederacy, with him taking 12.22% of the vote in that region while Roosevelt took 16.76%.[52] By countyIn a plurality of 1,396 counties, no candidate obtained a majority.[53] Wilson won 1,969 counties but held a majority in only 1,237, less than Bryan had had in any of his campaigns.[50] "Other(s)", mostly Roosevelt, won a plurality in 772 counties and a majority in 305 counties. Most of them in Pennsylvania (48), Illinois (33), Michigan (68), Minnesota (75), Iowa (49), South Dakota (54), Nebraska (32), Kansas (51), Washington (38), and California (44). Debs carried four counties: Lake and Beltrami in Minnesota, Burke in North Dakota, and Crawford in Kansas. These are the only counties ever to vote for the Socialist presidential nominee. Taft won a plurality in only 232 counties and a majority in only 35. In addition to South Dakota and California, where there was no Taft ticket, Taft carried no counties in Maine, New Jersey, Minnesota, Nevada, Arizona, and seven "Solid South" states.[50] Nine counties did not record any votes due to either black disenfranchisement or being inhabited only by Native Americans, who would not gain full citizenship for twelve more years. As of 2016[update], 1912 remains the last election in which the key Indiana counties of Hamilton and Hendricks, along with Walworth County, Wisconsin, Pulaski and Laurel Counties in Kentucky and Hawkins County, Tennessee have given a plurality to the Democratic candidate.[48]

Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005. Results by state

States that flipped from Republican to Democratic

States that flipped from Republican to ProgressiveClose statesMargin of victory less than 1% (13 electoral votes):

Margin of victory less than 5% (142 electoral votes):

Margin of victory between 5% and 10% (73 electoral votes):

Tipping point state:

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Progressive)

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

Counties with the Highest Percent of Vote (Socialist; incomplete)

Maps

Results in major cities Results of various cities within the top 100 municipalities by the 1910 United States census.

See also

Notes

References

Works cited

Further reading

Primary sources

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to United States presidential election, 1912.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||