「化学 」とは異なります。

科学 (かがく、英 : science )とは、世界 に関する知識 を検証可能 な仮説 と予測 の形で構築する体系的 な取り組みである[ 1] [ 2]

現代の科学は通常、物理世界 (自然界 )を研究する自然科学 (物理学 ・化学 ・生物学 など)、個人 や社会 を研究する行動科学 (経済学 ・心理学 ・社会学 など)[ 3] [ 4] 公理 や規則に準拠する形式体系 を研究する形式科学 (論理学 ・数学 ・理論計算機科学 など)[ 5] [ 6] [ 7] 科学的方法 や経験的証拠 (英語版 ) 演繹的推論 を主な方法論としているため、厳密には科学に含まれないとする意見もある[ 8] [ 9] 工学 や医学 など、科学的知識を実用的な目的のために利用する分野は応用科学 と呼ばれる[ 10] [ 11] [ 12]

科学の歴史 は歴史的記録の大部分にまたがっており、青銅器時代 の古代エジプト やメソポタミア に現代の科学のもっとも古いルーツがみられる。数学 ・天文学 ・医学 などの分野で彼らが残した業績は、古典古代 のギリシア自然哲学 へ受け継がれ、そこでは物理世界における事象の原因を自然界に求める正式な試みが行われた。また、インドの黄金時代 (英語版 ) インド・アラビア数字 の導入など、さらなる進展がみられた[ 13] :12 [ 14] [ 15] [ 16] 西ローマ帝国崩壊 (英語版 ) 中世前期 には、科学研究の衰退が起こったが、中世のルネサンス (英語版 ) カロリング・ルネサンス 、オットー朝ルネサンス (英語版 ) 12世紀ルネサンス )に入ると学問は再び隆盛を極めた。西ヨーロッパで散逸した古代ギリシアの写本の一部は、イスラーム黄金時代 の中東 で収集され、保存と拡充が行われた[ 17] ルネサンス 初頭には、ビザンチン・ギリシア人 (英語版 ) ビザンツ帝国 から西ヨーロッパへこれらの写本が持ち込まれ、再び散逸が防がれた。

10世紀 から13世紀 には、古代ギリシア文学 とアラビア科学 の成果が西ヨーロッパにもたらされたことによって自然哲学 が再生された[ 18] [ 19] [ 20] 16世紀 に科学革命 が始まると、古代ギリシアに由来する従来の概念と伝統から新しいアイデアや発見が生まれたことに伴い[ 21] [ 22] [ 23] 科学的方法 が知識の創出においてより大きな役割を果たすようになり、19世紀 に入ると自然哲学は自然科学 へと変化し[ 24] [ 25] [ 26]

科学における新たな知識の獲得は、世界に対する好奇心 と問題解決の意欲を持った科学者 による研究 によって推し進められている[ 27] [ 28] 学術機関 (英語版 ) 研究所 [ 29] 政府機関 [ 30] 企業 [ 31] 商品 ・兵器 ・医療 ・環境保護 などの開発を優先することで、科学的活動に影響を与えようとする科学政策 (英語版 )

日本語の「科学」という語は、近代の日本で造られた和製漢語 であり[ 32] 江戸 末期から明治 にかけて使用されていた「一科の学(一科学)」や「一科実用の学」などの表現に由来する。これらは、個々の専門的・実用的な学問分野を指す・数える表現であったとされ、他にも「一科ノ学業」「一科」「二科」「三科之学」「諸科」「百科の学」など、さまざまな表現があった。科学の二字が単純に連接する形で使われた最古の用例は、1832年(天保3年)に蘭学者 の高野長英 が書いた生理学 の教科書『医原枢要』にみられ、生理学を「医家ノ一科学」と説明している[ 33]

「科学」が独立する形で使われた確認可能な最古の用例は、1869年(明治2年)の『公議所日誌』第八ノ下、および同年に会津藩 の武士・広沢安任 が書いた『囚中八首衍義』にみられる。ただし、この時点で英語 の science と結び付けて考えられていたかどうか(現代と同様の語義であったか)は定かではなく、前者に関しては誤記の可能性が疑われている[ 33]

「科学」が明確に science の訳語として使われた最古の用例は、1875年(明治8年)の『文部省雑誌』第8号に掲載された「米国教育新聞抄訳活教授論」、および『東京英語学校教則』にみられる。その後、文部省 の出版物や専門書などで頻繁に用いられるようになり、明治末期にかけて、広範な知的探求や学問体系一般を指す現代的な語義が普及した。なお、明治中期までは、依然として「一科実用の学」という本来の意味も並存していたとされる。また、この時期から明治末期にかけて、科学者・科学的・自然科学・社会科学・科学技術などの関連語が生まれた。「科学」という語は、19世紀 末期から20世紀 初頭にかけて中国 に伝わり、中国語 でも用いられるようになった[ 33]

なお、1881年(明治14年)に出版された学術用語集 の『哲学字彙 』では、「科学」の他に「理学 」という訳語も当てられた[ 32] フランス で教育を受けた中江兆民 は、フランス語の philosophie 西周 が当てた訳語である「哲学 」の方が定着した[ 34]

中国 の研究では、宋代 の儒学者 ・陳亮 が使用していた「科挙之学」(科挙 で試される学問)の略語に由来するという説などが提唱されているが[ 33] [ 35] 大阪大学 名誉教授で日本語学 を専門とする田野村忠温は、これらの説は資料の誤読や誤認に基づいており、十分な証拠がないとして批判している[ 33]

英語 で科学を意味する science 14世紀 以来の中英語 において「知っている状態(the state of knowing)」という意味で使用されてきた。これはアングロ=ノルマン語 から接尾辞 -cience として借用されたものであり、さらにさかのぼると知識・認識・理解などを意味するラテン語 の名詞 scientia scientia sciens 派生 した名詞であり、「知る」という意味のラテン語の動詞 sciō scīre [ 36]

science の最終的な語源については複数の仮説がある。オランダ の言語学 者・印欧語学 者のミヒル・デ・ファン (英語版 ) sciō イタリック祖語 で「知る」という意味の *skije- *skijo- インド・ヨーロッパ祖語 で「切り刻む」という意味の *skh1 -ie *skh1 -io 語源辞典 『Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben (英語版 ) sciō nescīre 逆成 であり、secāre *sekH- *sḱʰeh2(i)- *skh2 - [ 37]

過去には、science はその語源に即して knowledge や study の同義語として使われていた。また、科学研究を行う人は「natural philosopher(自然哲学者)」や「man of sciecne(科学の人)」と呼ばれていた[ 38] ウィリアム・ヒューウェル は、メアリー・サマヴィル の著書『物理科学の諸関係 (英語版 ) [ 39] [ 40]

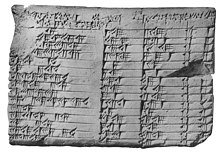

紀元前1,800年頃に作られた古代バビロニアの粘土板「プリンプトン322 」にはピタゴラス数 が記録されている 科学に明確な単一の起源はない。科学的思考は数万年の歳月をかけて徐々に発展し[ 41] [ 42] 先史時代 の科学では、宗教的儀式 を執り行う女性が中心的な役割を果たしていた可能性が高いと考えられている[ 43] [ 44] プロトサイエンス 」と表現している[ 45] [ 46] [ 47] [ 48] 現代中心主義 (英語版 ) [ 49]

科学的プロセスの直接的な証拠は、古代エジプト やメソポタミア などの初期文明で文字 体系が発明され、紀元前3,000年から紀元前1,200年頃に科学史 上の最古の文書記録が作成されたことで明確になる[ 13] :12–15 [ 14] 数学 ・天文学 ・医学 などの分野で業績を残した[ 50] [ 13] :12 。紀元前3千年紀 から、古代エジプト人は十進法 の数体系を発展させ[ 51] 幾何学 を用いて実用的な問題を解決し[ 52] 暦 を発明した[ 53] 超自然 的なものが含まれていた[ 13] :9 。

古代メソポタミア人は、さまざまな天然化学物質の特性に関する知識を陶器 やファイアンス焼き 、ガラス 、石鹸 、金属、漆喰 、および防水材の製造などに活用した[ 54] 占い のために占星術 や動物の生理学 ・解剖学 ・行動学 などの研究も行っていた[ 55] 医学 に強い関心を持っていたようであり、ウル第三王朝 時代にシュメール語 で書かれた最古の処方箋 の記録が残っている[ 54] [ 56] 知的好奇心 を満たすことにはほとんど関心がなかったようであり、明らかな実用性があるか、あるいは彼らの宗教信仰に関係する科学的主題のみが研究されていたと考えられている[ 54]

プラトン のアカデメイア を描いたモザイク画(Plato's Academy mosaic (英語版 ) 古典古代 に現代の科学者に相当する人々は存在しなかった。その代わりに、主に上流階級に属する男性の教養人が、余暇に自然に関するさまざまな調査を行っていた[ 57] ソクラテス以前の哲学者 たちによって「ピュシス (英語版 ) [ 58] [ 59]

ミレトス学派 の初期のギリシア哲学者たちは、超自然 的概念に頼らずに自然現象 を説明しようと試みた最初の人々であった。この学派はタレス によって創始され、のちにアナクシマンドロス とアナクシメネス によって受け継がれた[ 60] ピタゴラス教団 は複雑な数理哲学 を発展させ[ 61] :467–468 、数学 の発展に大きく貢献した[ 61] :465 。ギリシアの哲学者・レウキッポス とその弟子・デモクリトス は、原子論 を提唱した[ 62] [ 63] エピクロス は、この原子論 に基づいて完全に自然主義 (英語版 ) [ 64] ヒポクラテス は、体系的な医学の伝統を確立し[ 65] [ 66] 医学の父 」として知られるようになった[ 67]

初期の哲学的科学史における転換点は、ソクラテス が人間に関する事柄(人間の本性、政治的共同体の本質、人間の知識それ自体など)の研究に哲学を応用したことであった。たとえば、プラトン の対話篇にソクラテス式問答法 という問答法 が記録されている。これは「矛盾の原因となる仮説を着実に特定し排除することで、より良い仮説が得られる」とする弁証法 的方法であり、信念を形作る一般的に受け入れられている真理を探求し、それらの一貫性を厳密に精査するものであった[ 68] ソクラテス は、旧来の物理学研究について、あまりにも思弁的で自己批判 に欠けるとして批判を加えた[ 69]

紀元前4世紀 、アリストテレス は、目的論 的哲学の体系的な理論を大成させた[ 70] 紀元前3世紀 、ギリシアの天文学者・サモスのアリスタルコス は、太陽 を中心にすべての惑星 が公転する地動説 を最初に提唱した[ 71] [ 71] プトレマイオス の『アルマゲスト 』にみられるような、地球 を中心とする天動説 がルネサンス 初頭まで支持された[ 72] [ 73] アルキメデス は、微分積分学 の始まりに大きく貢献した[ 74] 大プリニウス は、後世に多大な影響を及ぼした百科事典『博物誌 』を著した[ 75] [ 76] [ 77]

数を表す位取り記数法 は、3世紀 から5世紀 の間にインド の交易路で生まれたと考えられている。この記数法は、効率的な算術 演算をより身近なものにし、やがて世界的に数学 の標準となった[ 78]

6世紀 に作られたウィーン写本 の1ページ目。クジャク が描かれている。西ローマ帝国の崩壊 (英語版 ) 5世紀 の西ヨーロッパ では知的衰退が生じ、世界に関する古代ギリシアの知識が損なわれた[ 13] :194 。とはいえ、古代世界の一般的知識の大部分は、イシドールス などの百科事典編纂者たちの努力によって保存された[ 79] ビザンツ帝国 は侵略者の攻撃に抵抗し、学問を保存・発展させることができた[ 13] :159 。6世紀 のビザンツ帝国の学者であるヨハネス・ピロポノス は、アリストテレス の物理学に疑問を呈し、インペトゥス理論 (英語版 ) [ 13] :307, 311, 363, 402 。この批判は、ガリレオ・ガリレイ などの後世の学者たちに影響を与え、10世紀後のガリレオはピロポノスの著作を広範に引用した[ 13] :307–308 [ 80]

古代末期 から中世前期 にかけて、自然現象は主にアリストテレス的なアプローチで検討された。このアプローチには、アリストテレス の四原因説 (質料因・形相因・作用因・目的因)が含まれる[ 81] ビザンツ帝国 では、多くの古代ギリシア文学 の書物が保存され、ネストリウス派 や単性論 者などの集団によってアラビア語 に翻訳された。アッバース朝 では、これらのアラビア語訳に基づき、アラビア人の科学者たちが研究をさらに伸展させた[ 82] 6世紀 から7世紀 にかけて、隣接するサーサーン朝 ではジュンディーシャープール学院 (英語版 ) [ 83]

アッバース朝 時代のバグダード [ 84] 知恵の館 では、13世紀 にモンゴルの侵攻 (英語版 ) アリストテレス主義 の研究が隆盛を極めた[ 85] イブン・ハイサム は、光学 の研究に人為的に管理された実験 を取り入れた[ 注釈 1] [ 87] [ 88] イブン・スィーナー が著した『医学典範 』は、医学界におけるもっとも重要な出版物の一つとされ、18世紀 にいたるまで使用された[ 89]

11世紀 には、ヨーロッパ の大部分がキリスト教 化し[ 13] :204 、1088年にはヨーロッパ最初の大学であるボローニャ大学 が誕生した[ 90] ラテン語 訳に対する需要が高まり[ 13] :204 、12世紀ルネサンス につながる大きな要因の一つとなった。西ヨーロッパ ではスコラ学 が栄え、自然界の対象を観察・記述・分類する実験が行われた[ 91] 13世紀 には、ボローニャの医学教師と学生たちが人体解剖を始め、世界初の解剖学 の教科書がモンディーノ・デ・ルッツィ による人体解剖に基づいて作成された[ 92]

ニコラウス・コペルニクス の著書『天球の回転について 』(1543年)に描かれている地動説 を表した図ルネサンス 初頭には、長年にわたって堅持されてきた知覚 に関する形而上学 的観念に挑戦したり、カメラ・オブスクラ や望遠鏡 などの技術の改良・発展に寄与するなど、光学 分野における進展が重要な役割を果たした。また、ロジャー・ベーコン 、ヴィテロ 、ジョン・ペッカム (英語版 ) スコラ学 的存在論 を大成させた。そこでは、感覚から始まり、知覚へ続き、最終的に個別的・普遍的イデア の統覚 に終わるという因果連鎖が提唱された[ 86] :Book I 。ルネサンスの芸術家 たちは、現在では観点主義 (透視投影 )として知られる視覚のモデルを研究・活用した。なお、この理論では、アリストテレスが提唱した四原因 のうち、形相因・質料因・目的因の3つのみが使用されている[ 93]

16世紀 には、ニコラウス・コペルニクス が地動説 を提唱し、惑星は地球 ではなく太陽 を中心に公転していると主張した。これは、惑星の公転周期 が中心からの距離に応じて長くなるという定理に基づいており、コペルニクスはこれがプトレマイオス のモデルと矛盾することを発見したのである[ 94]

ヨハネス・ケプラー をはじめとする学者たちは、目 の唯一の機能が知覚であるという観念に挑戦し、光学研究の重点を目から光 の伝播に移した[ 93] [ 95] 惑星運動の法則 を発見し、コペルニクスが提唱した地動説のモデルを改良したことでもっともよく知られている。また、アリストテレスの形而上学を否定せず、自身の研究を「天球の音楽 (英語版 ) [ 96] ガリレオ は、天文学・物理学・工学などの分野で重要な業績を残したが、地動説を支持したことでローマ教皇・ウルバヌス8世 から迫害を受けることとなった[ 97]

この時代に発明された印刷機 は、当時の自然観とは大きく異なる意見も含む、学術的な議論を広く出版するために使用された[ 98] フランシス・ベーコン とルネ・デカルト は、アリストテレス主義 から離れた新しい形態の科学を支持する哲学的議論を公表した。ベーコンは実験の重要性を訴え、アリストテレスが提唱した形相因と目的因の概念に疑問を呈し、科学は自然法則 を研究し、人類全体の進歩を追及すべきだと主張した[ 99] [ 100]

アイザック・ニュートン 『自然哲学の数学的諸原理 』(1687年)啓蒙時代初頭にアイザック・ニュートン が著した『自然哲学の数学的諸原理 』は、古典力学 の基礎を築き、後世の物理学者たちに多大な影響を与えた[ 101] ゴットフリート・ライプニッツ は、特別な形相因や目的因などは存在せず、異なる種類の物体もすべて同じ一般的な自然法則に従っているとし、アリストテレスの自然学 で用いられた用語を非目的論 的(機械論 的)な用法で物理学 に取り入れた。これは物体に対する見方の転換を意味しており、すなわち「物体に目的は内在していない」と考えられるようになったのである[ 102]

この時代に宣告された科学の目的と価値は、より多くの食料や衣類などの物品を得るという物質的 な意味で、人間の生活を改善する富と発明を創出することであった。ベーコン は「科学の真の正当な目標は、新たな発明と富の恵代によって人間の生活を豊かにすることである」と述べ、人間の幸福にほとんど寄与せず、「微妙で崇高な、あるいは愉快な(思索の)煙」に過ぎない哲学的・精神的な観念にふけらないよう科学者に勧めた[ 103]

啓蒙時代における科学は、学会 や学術団体(アカデミー )が主導し[ 104] [ 105] 啓蒙思想 家たちは、ガリレオ、ケプラー、ボイル、そしてニュートンといった科学界における先駆者たちを、当時のあらゆる物理的・社会的分野の指針とした[ 106] [ 107]

18世紀 には、医学 [ 108] 物理学 [ 109] 化学 が一つの学問分野として成熟し[ 110] 磁気 と電気 に対する新たな理解が得られ[ 111] カール・フォン・リンネ は分類学 を創始した[ 112] デイヴィッド・ヒューム をはじめとするスコットランド の啓蒙思想家たちは『人間本性論 』を展開し、ジェームズ・バーネット (英語版 ) アダム・ファーガソン 、ジョン・ミラー (英語版 ) ウィリアム・ロバートソン (英語版 ) [ 113] 社会学 は、この運動から生まれたと考えられている[ 114] アダム・スミス が著した『国富論 』は、近代経済学 の最初の著作とされることが多い[ 115]

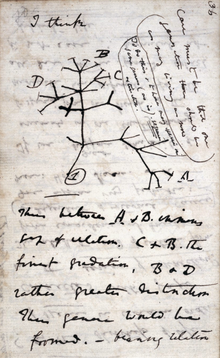

1837年にチャールズ・ダーウィン によって初めて描かれた系統樹 の図 19世紀 には、現代の科学を特徴づける多数の要素が形作られた。生命科学と物理科学の変革、精密機器の広範な使用、「生物学者」「物理学者」「科学者」などの用語の登場、自然を研究する者の専門職化、社会の多方面における科学者の文化的権威の獲得、諸国家の産業化、通俗科学 作品の流行、そして科学雑誌 の登場などがあげられる[ 116] ヴィルヘルム・ヴント が世界初の心理学研究所を設立し、心理学 が哲学 から独立した学問として確立された[ 117]

1858年には、チャールズ・ダーウィン とアルフレッド・ラッセル・ウォレス の各々が自然選択 による進化論 を提唱し、さまざまな植物や動物の起源と進化を説明した。この理論は、1859年に出版されたダーウィンの『種の起源 』で詳説された[ 118] グレゴール・ヨハン・メンデル が論文『植物雑種に関する実験 (英語版 ) [ 119] [ 120]

19世紀初頭、ジョン・ドルトン はデモクリトス の原子論 に基づいて現代的な原子論を提唱した[ 121] エネルギー保存の法則 、運動量保存の法則 、質量保存の法則 は、この宇宙は非常に安定しており、資源の損失がほとんどない可能性を示唆した。しかし、蒸気機関 の発明と産業革命 の到来により、あらゆるエネルギー が同一の質 (英語版 ) 仕事 や他の種類のエネルギーへの変換の容易さが異なることが明らかになった[ 122] 熱力学の法則 の解明につながり、宇宙の自由エネルギー は常に減少を続けており、閉じた宇宙 のエントロピー は時間が経過するにつれて増加すると考えられるようになった[ 注釈 2]

エルステッド 、アンペール 、ファラデー 、マクスウェル 、ヘヴィサイド 、ヘルツ らの貢献により、電磁気学 が確立されたのもこの時代である。この理論は、従来のニュートンの枠組みでは容易に答えられない新たな問題を提起した。X線 の発見は、1896年のアンリ・ベクレル とマリ・キュリー による放射能 の発見につながり[ 125] ノーベル賞 を初めて2度にわたって受賞した人物となった[ 126] 亜原子粒子 である電子 が発見された[ 127]

1987年に宇宙望遠鏡からのデータを用いて作成されたオゾンホール の図 20世紀 前半には、抗生物質 と人工肥料 の発明により、世界的に人類の生活水準が向上した[ 128] [ 129] オゾン層の破壊 や海洋酸性化 、富栄養化 、および気候変動 (地球温暖化 )などの有害な環境問題 が公衆の注目を集め、環境学 の発展が促進された[ 130]

科学実験の規模と資金は大幅に拡大し、巨大科学 が行われるようになった[ 131] 第一次世界大戦 と第二次世界大戦 、および冷戦 によって刺激された広範な技術革新は、宇宙開発競争 や核軍拡競争 (英語版 ) 大国 間競争の要因となった[ 132] [ 133] [ 134]

20世紀後半に入ると、女性の積極的な採用と性差別 の撤廃により、女性科学者の数が大幅に増加したが、一部の分野では依然として大きな格差が残った[ 135] 宇宙マイクロ波背景放射 が発見され[ 136] 定常宇宙論 が否定された。その後、ジョルジュ・ルメートル が提唱したビッグバン 理論が支持されるようになった[ 137] アポロ11号 が人類初の有人月面着陸を成功させ、月面から多数のサンプル(月の石 )を地球に持ち帰った[ 138] [ 139]

20世紀全体を通して、複数の科学分野で根本的な変化が生じた。20世紀初頭、現代的総合 (英語版 ) ダーウィン の進化論 と古典遺伝学 が統合され、進化論は統一理論となった[ 140] アインシュタイン の相対性理論 と量子力学 の発展は、古典力学 を補完し、極端なスケールにおける長さ ・時間 ・重力 の物理を説明可能にした[ 141] [ 142] 集積回路 (IC)の普及と通信衛星 の組み合わせは情報技術革命をもたらし、グローバルなインターネット とスマートフォン を含むモバイルコンピューティング (英語版 ) 一般システム理論 やコンピュータを活用した科学的モデリング などの分野も発展した[ 143]

2019年にイベントホライズンテレスコープ の研究チームが作成したM87 の超大質量ブラックホール の予測画像 2003年には、ヒトゲノム計画 が完了し、ヒトゲノム のすべての遺伝子が同定・地図化された[ 144] iPS細胞 が作成され、成体細胞を幹細胞に変換し、体内のあらゆる種類の細胞に変化させることが可能となった[ 145] ヒッグス粒子 が観測され、素粒子物理学 の標準模型 で予測された最後の粒子が発見された[ 146] 一般相対性理論 で存在が予言されていた重力波 が初めて観測された [ 147] [ 148] イベントホライズンテレスコープ が、ブラックホール の降着円盤 の直接撮像に成功した[ 149]

現代の科学は一般的に、自然科学 ・社会科学 ・形式科学 の3つに大別される[ 7] 術語体系 と専門知識を有することが多いさまざまな下位分野がこれらに連なる[ 150] 経験的観察 (英語版 ) 経験科学 であり[ 151] 検証 できる再現性 が備わっている[ 152]

自然科学 は、物理的な世界 (自然界 )を研究する分野である。生命科学 と物理科学 の2つの主要分野に分けられ、さらに専門的な領域に細分化される。たとえば、物理科学は物理学 ・化学 ・天文学 ・地球科学 などに細分化される。現代の自然科学は、古代ギリシア で始まった自然哲学 を受け継いだものである。ガリレオ 、デカルト 、ベーコン 、ニュートン は、より数学的かつより実験的なアプローチを体系的に用いることの利点について論じたが、哲学的考察や推測、および前提の措定なども(見過ごされることが多いが)依然として自然科学には必要不可欠である[ 153] 発見科学 (英語版 ) 16世紀 の博物学 を受け継いだものである[ 154]

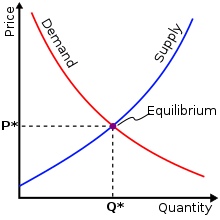

経済学 における需要と供給 を表した図。需要曲線と供給曲線が均衡点で交差している。社会科学 は、人間の行動と社会の機能を研究する分野である[ 3] [ 4] 人類学 ・経済学 ・歴史学 ・人文地理学 ・政治学 ・心理学 ・社会学 など、多くの分野を含むが、これらに限定されない[ 3] 機能主義 、紛争理論 、相互作用論 (英語版 ) [ 3] 歴史学研究法 、事例研究 、異文化間研究 (英語版 ) 統計 的アプローチが採用される場合もある[ 3]

形式科学 は、形式体系 を用いて知識を創出する分野である[ 155] [ 5] [ 6] 公理 から定理 を推論するために用いられる抽象的構造 (英語版 ) [ 156] 数学 [ 157] [ 158] システム論 ・理論計算機科学 などがこれに含まれる。形式科学は、知識の一分野を客観的かつ慎重に、および体系的に研究するという点で先述の二大分野と類似している。しかし、演繹的推論 にのみ依存し、抽象的概念を検証するために経験的証拠 (英語版 ) 経験科学 とは異なる[ 8] [ 159] [ 152] アプリオリ な学問であり、そのため科学に含まれるかどうかについては意見が分かれている[ 160] [ 161] 微分積分学 は当初、物理学 における運動を理解するために発明された[ 162] 数学 に大きく依存している経験科学の分野としては、他にも数理物理学 [ 163] 数理化学 (英語版 ) [ 164] 数理生物学 [ 165] 数理経済学 [ 166] 数理ファイナンス [ 167]

応用科学 は、実用的な目的を達成するために科学的方法 と科学的知識を利用する分野である[ 168] [ 12] 基礎科学 と対比されることが多い[ 169] [ 170] 工学 や医学 などがその代表例としてあげられる。工学は、構造物や機械、およびその他の技術を発明・設計・構築するために科学的諸原理を利用する分野であり[ 171] [ 172] 医学 は、傷害や疾病の予防・診断・治療を通じて健康を維持・回復することにより病人の介抱を行う分野である[ 173] [ 174]

計算機科学 は、現実世界の状況をシミュレート するためにコンピュータ の演算能力を利用する分野であり、形式的な数学的考察だけでは得られない科学的諸問題に対するより深い理解の創出を可能にするものである。機械学習 や人工知能 の利用は、科学に対する計算的貢献の主力になりつつあり、たとえば、ランダムフォレスト 、トピックモデリング (英語版 ) エージェントベース計算経済学 (英語版 ) バイアス がみられたり、人間と比べて性能が劣ることもある[ 175] [ 176]

学際的科学 は、2つ以上の分野にまたがる研究領域である[ 177] 生物学 と計算機科学 を組み合わせたバイオインフォマティクス [ 178] 認知科学 などがその代表例としてあげられる。複数の分野にまたがって研究を行うという発想は古代ギリシア の時代から存在し、20世紀 に再び人気が高まった[ 179]

科学研究は、基礎研究 と応用研究 に分けられる。基礎研究は純粋に新たな知識を追い求めるものであり、応用研究はその知識を用いて実用的な問題の解決策を探るものである[ 180] [ 181]

科学的方法 は終わることのない再帰的プロセスである科学研究は、自然界 における事象を再現可能 な方法で客観的 に説明しようとする科学的方法 を用いて行われる[ 182] 公理 )を自明のものとして受け入れている。すなわち、あらゆる理性的観測 者が間主観的 (英語版 ) 科学的実在論 )、自然法則 がこの客観的現実を支配していること(自然主義 (英語版 ) [ 2] 測定 ・定量的モデリングなどで広範に利用されることから、仮説 ・理論 ・法則の形成には数学 が欠かせないものとなっている[ 183] 統計学 も用いられる。これにより、科学者が実験結果の信頼性を評価することが可能となる[ 184]

科学的方法を用いた研究では、説明的な思考実験 や仮説 は、倹約の原則 が適用されていること、および知の統合 (英語版 ) [ 185] 反証可能 な予測を行うために用いられ、通常は実験によって検証される前に提示される。予測が反証されることは、研究が正常に進展していることの証となる[ 182] :4–5 [ 186] 実験 が特に重要なのは、相関の誤謬 を避けるために因果関係 を立証するためであるが、天文学 や地質学 などの分野においては、予測された観測がより適切な場合もある[ 187]

仮説が誤っていることが判明した場合、それは修正されるか、あるいは破棄される。仮説が検証に耐えることができれば、科学理論 (英語版 ) 妥当 に推論 された自己矛盾のないモデルや枠組みのことである。科学理論は通常、観測結果の集合の振る舞いを単一の仮説よりもはるかに広範に説明し、一般的には単一の理論に多数の仮説が論理的に結びつけられる。したがって、科学理論はさまざまな仮説を説明するための仮説と言うことができる。その意味では、理論は仮説とほぼ同じ科学的原理にしがたって定式化される。また、観測結果を論理的、物理的、あるいは数学的表現で記述・描写するモデル が作成されることもあり、そこから実験によって検証可能な仮説が新たに生み出されることもある[ 188]

仮説を検証する実験を行う際に、科学者が特定の結果を選好してしまう可能性がある(科学における不正行為 )[ 189] [ 190] バイアス は、透明性の確保、入念な実験の計画 、および実験の結果と結論に対する徹底的な査読 などを通じて排除される[ 191] [ 192] [ 193] 確証バイアス の影響を最小限に抑えつつ、高度に創造的な問題解決を可能にするものとなっている[ 194] 合意の形成 と結果の再現 を可能にする性質である間主観的検証可能性 (英語版 ) [ 195]

1869年11月4日に出版された『ネイチャー 』創刊号の表紙 科学研究はさまざまな文献で公表される[ 196] 科学雑誌 (ジャーナル)であり、大学やその他の研究機関で行われた研究の結果を伝達・記録する役割を果たしている。また、各分野ごとに専門のジャーナルが存在し、その分野内の研究が論文 形式で公表されていることが多い。最古の科学雑誌である『ジュルナル・デ・サヴァン 』とそれに次ぐ『フィロソフィカル・トランザクションズ 』は、1665年に創刊された。それ以来、科学雑誌の数は着実に増加を続けており、2021年の国際STM出版社協会 (英語版 ) 査読 付き科学雑誌の数は46,736誌と推定されている[ 197]

再現性の危機 とは、社会科学 と生命科学 の一部に影響を与えている進行中の方法論的危機であり、過去に行われた多数の研究の結果が再現できないことが明らかになった問題である[ 198] [ 199] メタ科学 (英語版 ) [ 200]

科学に偽装することで本来は得られない正当性を得ようとする意見や研究分野は、擬似科学 、境界科学 、あるいはジャンク・サイエンス (英語版 ) [ 201] [ 202] リチャード・ファインマン は、研究者自身が科学を行っていると信じており、実際に科学を行っているように見えるが、結果を厳密に評価させる誠実性に欠けるものを「カーゴ・カルト 科学」と名付けた[ 203] [ 204]

また、科学的論争には政治的・イデオロギー的なバイアスが含まれることもある。「悪い科学(bad science)」と呼ばれる研究も存在し、これは意図はよいものの、科学的概念の説明が不正確、時代遅れ、不完全、または過度に単純化されている研究を指す。「科学における不正行為 」という類似の用語は、研究者による意図的なデータの捏造や、発見の功績を意図的に誤った人物に帰するなどの不正行為を指す[ 205]

クーン のパラダイム論 によれば、プトレマイオス の天文学における周転円 の追加は、そのパラダイム内における「普通の科学」であったのに対し、コペルニクス的転回 はパラダイムシフト であった科学哲学 にはさまざまな学派がある。もっとも一般的な立場は、観察を含むプロセスによって知識が生み出されるとする経験主義 である。この見方では、科学理論 (英語版 ) [ 206] 経験的証拠 (英語版 ) 帰納主義 (英語版 ) ベイズ主義 と仮説演繹法 である[ 207] [ 206]

経験主義は、デカルト の思想に由来する合理主義 とは対照的な立場にある。合理主義では、観察ではなく人間の理性によって知識が生み出されるとされる[ 208] 批判的合理主義 は、20世紀 に登場した対照的なアプローチであり、オーストリア系イギリス人の哲学者であるカール・ポパー が提唱した。ポパーは、経験主義による理論と観察の関係性の説明を否定し、理論は観察から生まれるのではなく、観察が理論に基づいて行われると主張した。また、理論Aが観察と矛盾する一方で、理論Bが観察に耐えた場合にのみ、理論Aは観察による影響を受けるとした[ 209] 検証可能性 を反証可能性 に、経験的方法として帰納を反証にそれぞれ置き換えることを提案した[ 209] 試行錯誤 [ 210] [ 211]

もう一つのアプローチである道具主義 は、理論を現象の説明と予測のための道具として捉え、その有用性を重視するものである。この立場では、科学理論はブラックボックス とみなされ、その入力(初期条件)と出力(予測)のみが重要とされる。帰結や理論的実体、および論理構造は、無視すべきものとされる[ 212] 構成的経験主義 (英語版 ) [ 213]

トーマス・クーン は、観察と評価のプロセスは、ある一つのパラダイム 内(つまり、観測結果と矛盾しない論理的に首尾一貫した「世界の肖像」の中)で行われると主張した。クーンは、「通常の科学(normal science)」を、あるパラダイム内で行われる観察と「謎解き」のプロセスであるとし、あるパラダイムが別のパラダイムに取って代わられるパラダイムシフト の際に「革命的科学(revolutionary science)」が発生するとした[ 214] 相対主義 とは異なるとされる[ 215]

「創造科学 」などの論争を呼ぶ運動に対する科学的懐疑主義 の議論で引用されることが多いアプローチとして、方法論的自然主義 (英語版 ) 超自然 の区別を設け、科学は「自然な」説明に限定されるべきだと主張している[ 216] 経験的研究 に厳密に従うことを要求する立場でもある[ 217]

科学界 (英語版 ) 社会的ネットワーク である。このコミュニティは、各分野で活動する小規模なグループから構成される。科学者たちは、学術誌や学会での議論・討論を通じた相互評価 (英語版 ) 査読 によって、研究方法の品質を維持し、結果の解釈における客観性を保っている[ 218]

マリ・キュリー は、ノーベル賞 を2度にわたって受賞した初の人物である。1903年に物理学賞を、1911年に化学賞を受賞した。科学者 とは、関心分野の新たな知識を創出するために科学研究を行う人のことである[ 219] [ 220] 学位 を取得している。なお、最高学位は博士号 (PhD)である[ 221]

科学者は、現実世界に対する強い好奇心と、健康・国家・環境・産業の利益のために科学的知識を応用したいという欲求を示していることが多い。その他の動機としては、同僚からの評価や名声の獲得などがあげられる。現代では、多くの科学者が科学分野の高度な学位を有し、学術界・産業界・政府機関・非営利組織など、さまざまな経済部門 (英語版 ) [ 222] [ 223] [ 224] [ 225]

歴史的にみて、科学は男性が支配的な分野であったが、注目すべき例外も存在する。女性の科学者 (英語版 ) 差別 に直面した。たとえば、頻繁に就職の機会を逃したり、自身の業績に対する評価を否定されてきた[ 226] 性役割 (ジェンダーロール)に対する反抗の結果と考えられている[ 227]

プロイセン科学アカデミー 創立200周年を記念して1900年に撮影された科学者たちの集合写真科学者が交流・議論・討論を行うために組織される学会 は、ルネサンス の時代から存在する[ 228] [ 229] [ 230] [ 231] 職能団体 である。典型的な活動には、新しい研究結果の発表と議論のための定期的な会議の開催や、その分野の学術誌の発行や賛助が含まれる。一部の学会は職能団体 として機能し、公共の利益や会員の集団的利益のために会員活動を規制している。

19世紀 に始まった科学の専門職化は、イタリアのアッカデーミア・デイ・リンチェイ (1603年)[ 232] 王立協会 (1660年)[ 233] フランスの科学アカデミー (1666年)[ 234] アメリカの科学アカデミー (1863年)[ 235] カイザー・ヴィルヘルム学術振興協会 (1911年)[ 236] 中国科学院 (1949年)[ 237] 科学アカデミー の創設によって部分的に可能となった。国際学術会議 などの国際的な科学組織は、科学の進歩のために国際協力 に取り組んでいる[ 238]

科学賞 は通常、ある分野に顕著な貢献を行った個人や組織に授与される。多くの場合、これらは権威のある機関によって与えられるため、これらを受賞することは科学者にとって大きな名誉とされる。ルネサンス以来、科学者たちはメダル・賞金・称号などを授与されてきた。高い権威を持つとされるノーベル賞 は、医学・物理学・化学の進歩に多大な貢献を行った人々に毎年授与されている[ 239]

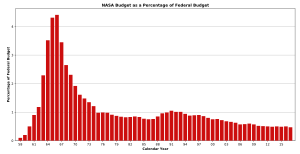

アメリカ合衆国 の国家予算に占めるアメリカ航空宇宙局 (NASA)の予算は、1966年の4.4%をピークに減少傾向にある科学研究の資金は、競争的プロセスを通じて提供されることが多い。このプロセスでは、潜在的な研究プロジェクトが評価され、もっとも有望なものだけが資金を得る。政府・企業・財団などが運営するこのようなプロセスは、限られた資金の中から予算が配分される。ほとんどの先進国 では、研究資金の総額はGDP の1.5%から3%の間に収まる[ 240] OECD 加盟国では、科学技術分野の研究開発の約3分の2を産業界が、20%を大学が、10%を政府が担っている。一部の分野は政府からの資金提供の割合が高く、特に社会科学と人文科学 の研究では政府が主導的役割を果たしている。開発途上国 では、基礎科学研究の資金の大部分を政府が提供している[ 241]

多くの政府は、科学研究を支援するための専門機関を設けている。たとえば、アメリカの国立科学財団 [ 242] 国立科学技術研究評議会 (英語版 ) [ 243] 連邦科学産業研究機構 [ 244] 国立科学研究センター [ 245] マックス・プランク協会 [ 246] 科学研究高等評議会 (英語版 ) [ 247] [ 248]

科学政策 (英語版 ) 科学的コンセンサス を公共政策の策定に適用する行為を指すこともある。公共政策が市民の福祉に関心を持つのと同様に、科学政策の目標は科学技術が公共にどのようにもっともよく貢献できるかを考慮することである[ 249] 固定資産 や知的インフラの資金調達に直接的な影響を与えることができる[ 250]

ヒューストン自然科学博物館 (英語版 ) 一般市民向けの科学教育 は、たいていの学校教育 に組み込まれており、インターネット上の教育コンテンツ(YouTube やカーンアカデミー など)、博物館 、科学雑誌 、およびブログ などがそれを補完している。アメリカ科学振興協会 (AAAS)などの主要組織は、科学を哲学や歴史学と並ぶリベラル・アーツ の学習伝統の一部とみなしている[ 251] 科学リテラシー は主に、科学的方法 、測定の単位と方法、経験主義 、統計学 の基礎(相関 、定性的 ・定量的 観察、総統計 (英語版 ) 物理学 ・化学 ・生物学 ・生態学 ・地質学 ・計算機科学 などの主要分野の基本的理解に関係する。学生が高等教育 の段階に進むにつれて、カリキュラムの内容はより深く掘り下げたものになる。カリキュラムに含まれる伝統的な科目は自然科学と形式科学だが、近年では社会科学や応用科学も含まれるようになっている[ 252]

マスメディア は、科学界全体における信頼性の観点から、競合する科学的主張を正確に描写することを妨げる圧力に直面している。科学的論争において、異なる立場にどの程度の重みを置くべきかを判断するには、その問題に関する相当の専門知識が必要な場合がある[ 253] ジャーナリスト は少なく、特定の科学的問題に詳しい専門記者であっても、突然に取り扱うことを求められた他の科学的問題については無知な可能性がある[ 254] [ 255]

『ニュー・サイエンティスト 』、『サイエンティフィック・アメリカン 』、『Science & Vie (英語版 ) 科学雑誌 は、より広い読者層の受容に応え、特定の研究分野における注目すべき発見や進歩など、人気のある研究分野の非専門家向けの要約を提供している[ 256] スペキュレイティブ・フィクション が多いサイエンス・フィクション の作品では、科学の考え方や方法が一般大衆に伝えられている[ 257]

科学的方法は科学界で広く受け入れられているが、社会の一部の人々は、特定の科学的立場に否定的であったり、科学自体に懐疑的であったりする。たとえば、「新型コロナウイルス感染症 (COVID-19)は米国にとって大きな健康上の脅威ではない」という一般的な考え(2021年8月に米国人の39%が信じていた[ 258] 気候変動 (地球温暖化 )は米国にとって大きな脅威ではない」という信念(2019年後半から2020年初頭にかけて、同じく米国人の40%が信じていた[ 259] [ 260]

科学的権威は、専門性や信頼性が欠如している、あるいは偏りがあるとみなされることがある。

一部の疎外された 社会集団は、反科学的態度を持っている。これらの集団に関しては、非倫理的な人体実験 で搾取されてきた歴史を持つことが部分的理由として考えられる[ 261]

科学者のメッセージは、深く根付いた既存の観念や道徳観と相容れないことがある。

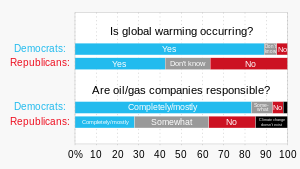

科学的メッセージの伝達は、受け手の学習スタイルに適切に合わせられていないことがある。 反科学的態度は、社会集団における拒絶への恐れによって引き起こされているように見えることが多い。たとえば、気候変動に関して、右派のアメリカ人は22%のみが脅威と認識しているが、左派は85%が脅威と認識している。つまり、左派に属する人は、気候変動を脅威と考えなければ軽蔑されたり、その社会集団から拒絶されたりする可能性がある[ 262] [ 263]

アメリカ合衆国 における地球温暖化 に対する世論を政党別に示した図[ 264] 科学に対する態度は、政治的意見や目標によって決定されることが多い。政府・企業・利益団体 は、法的・経済的圧力を用いて研究者に影響を与えようとすることで知られている。反知性主義 、宗教的信念に対する脅威との認識、商業的利益の恐れなど、複数の要因が科学の政治化 (英語版 ) [ 265] [ 266] [ 267] 地球温暖化に関する論争 、農薬の健康への影響 (英語版 ) たばこ病 などがあげられる[ 267] [ 268]

^ Wilson, E. O. (1999). “The natural sciences” . Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (Reprint ed.). New York: Vintage. pp. 49 –71. ISBN 978-0-679-76867-8 . https://archive.org/details/consilienceunity00wils_135 ^ a b Heilbron, J. L. (2003). “Preface”. The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science . New York: Oxford University Press. pp. vii–x. ISBN 978-0-19-511229-0 . "...modern science is a discovery as well as an invention. It was a discovery that nature generally acts regularly enough to be described by laws and even by mathematics; and required invention to devise the techniques, abstractions, apparatus, and organization for exhibiting the regularities and securing their law-like descriptions."

^ a b c d e Colander, David C.; Hunt, Elgin F. (2019). “Social science and its methods”. Social Science: An Introduction to the Study of Society (17th ed.). New York: Routledge. pp. 1–22

^ a b Nisbet, Robert A.; Greenfeld, Liah (16 October 2020). "Social Science" . Encyclopædia Britannica . 2022年2月2日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2021年5月9日閲覧 。

^ a b Löwe, Benedikt (2002). “The formal sciences: their scope, their foundations, and their unity”. Synthese 133 (1/2): 5–11. doi :10.1023/A:1020887832028 . ISSN 0039-7857 .

^ a b Rucker, Rudy (2019). “Robots and souls” . Infinity and the Mind: The Science and Philosophy of the Infinite (Reprint ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 157–188. ISBN 978-0-691-19138-6 . オリジナル の2021-02-26時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20210226212447/http://www.rudyrucker.com/infinityandthemind/#calibre_link-328 2021年5月11日 閲覧。

^ a b Cohen, Eliel (2021). “The boundary lens: theorising academic activity” . The University and its Boundaries: Thriving or Surviving in the 21st Century . New York: Routledge. pp. 14–41. ISBN 978-0-367-56298-4 . https://www.routledge.com/The-University-and-its-Boundaries-Thriving-or-Surviving-in-the-21st-Century/Cohen/p/book/9780367562984 2021年5月4日 閲覧。

^ a b Fetzer, James H. (2013). “Computer reliability and public policy: Limits of knowledge of computer-based systems”. Computers and Cognition: Why Minds are not Machines . Newcastle, United Kingdom: Kluwer. pp. 271–308. ISBN 978-1-4438-1946-6

^ Nickles, Thomas (2013). “The Problem of Demarcation”. Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem . The University of Chicago Press. p. 104 ^ Fischer, M. R.; Fabry, G (2014). “Thinking and acting scientifically: Indispensable basis of medical education” . GMS Zeitschrift für Medizinische Ausbildung 31 (2): Doc24. doi :10.3205/zma000916 . PMC 4027809 . PMID 24872859 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4027809/ . ^ Sinclair, Marius (1993). “On the Differences between the Engineering and Scientific Methods” . The International Journal of Engineering Education . オリジナル の2017-11-15時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20171115220102/https://www.ijee.ie/contents/c090593.html 2018年9月7日 閲覧。 ^ a b Bunge, M. (1966). “Technology as Applied Science”. In Rapp, F.. Contributions to a Philosophy of Technology . Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 19–39. doi :10.1007/978-94-010-2182-1_2 . ISBN 978-94-010-2184-5

^ a b c d e f g h i j Lindberg, David C. (2007). The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226482057

^ a b Grant, Edward (2007). “Ancient Egypt to Plato” . A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century . New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-0-521-68957-1 . https://archive.org/details/historynaturalph00gran/page/n16

^ Building Bridges Among the BRICs Archived 2023-04-18 at the Wayback Machine ., p. 125, Robert Crane, Springer, 2014^ Keay, John (2000). India: A history 132 . ISBN 978-0-87113-800-2 . https://archive.org/details/indiahistory00keay/page/132 . "The great era of all that is deemed classical in Indian literature, art and science was now dawning. It was this crescendo of creativity and scholarship, as much as ... political achievements of the Guptas, which would make their age so golden." ^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). “Islamic science”. The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. pp. 163–192. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7 ^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). “The revival of learning in the West”. The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. pp. 193–224. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7 ^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). “The recovery and assimilation of Greek and Islamic science”. The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. pp. 225–253. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7 ^ Sease, Virginia; Schmidt-Brabant, Manfrid. Thinkers, Saints, Heretics: Spiritual Paths of the Middle Ages. 2007. Pages 80–81 . Retrieved 2023-10-06

^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). “The legacy of ancient and medieval science”. The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. pp. 357–368. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7 ^ Grant, Edward (2007). “Transformation of medieval natural philosophy from the early period modern period to the end of the nineteenth century” . A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century . New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 274 –322. ISBN 978-0-521-68957-1 . https://archive.org/details/historynaturalph00gran ^ Principe, Lawrence M. (2011). “Introduction”. Scientific Revolution: A Very Short Introduction . New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-19-956741-6 ^ Harrison, Peter (2015). The Territories of Science and Religion . University of Chicago Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0-226-18451-7 . "The changing character of those engaged in scientific endeavors was matched by a new nomenclature for their endeavors. The most conspicuous marker of this change was the replacement of "natural philosophy" by "natural science". In 1800 few had spoken of the "natural sciences" but by 1880 this expression had overtaken the traditional label "natural philosophy". The persistence of "natural philosophy" in the twentieth century is owing largely to historical references to a past practice (see figure 11). As should now be apparent, this was not simply the substitution of one term by another, but involved the jettisoning of a range of personal qualities relating to the conduct of philosophy and the living of the philosophical life." ^ Cahan, David, ed (2003). From Natural Philosophy to the Sciences: Writing the History of Nineteenth-Century Science . University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-08928-7 ^ Lightman, Bernard (2011). “13. Science and the Public”. In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter. Wrestling with Nature: From Omens to Science . University of Chicago Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0 ^ MacRitchie, Finlay (2011). “Introduction” . Scientific Research as a Career . New York: Routledge. pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-1-4398-6965-9 . https://www.routledge.com/Scientific-Research-as-a-Career/MacRitchie/p/book/9781439869659 2021年5月5日 閲覧。 ^ Marder, Michael P. (2011). “Curiosity and research” . Research Methods for Science . New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-0-521-14584-8 . https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/research-methods-for-science/1C04E5D747781B68C52A79EE86BF584B 2021年5月5日 閲覧。 ^ de Ridder, Jeroen (2020). “How many scientists does it take to have knowledge?” . What is Scientific Knowledge? An Introduction to Contemporary Epistemology of Science . New York: Routledge. pp. 3–17. ISBN 978-1-138-57016-0 . https://www.routledge.com/What-is-Scientific-Knowledge-An-Introduction-to-Contemporary-Epistemology/McCain-Kampourakis/p/book/9781138570153 2021年5月5日 閲覧。 ^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). “Islamic science”. The beginnings of Western science: the European Scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. pp. 163–192. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7 ^ Szycher, Michael (2016). “Establishing your dream team” . Commercialization Secrets for Scientists and Engineers . New York: Routledge. pp. 159–176. ISBN 978-1-138-40741-1 . https://www.routledge.com/Commercialization-Secrets-for-Scientists-and-Engineers/Szycher/p/book/9781498730600 2021年5月5日 閲覧。 ^ a b 高野繁男 「『哲学字彙』の和製漢語 : その語基の生成法・造語法 」『人文学研究所報』第37巻、神奈川大学人文学研究所、2004年3月30日、87-108頁、NCID AN00122854 、2024年12月27日 閲覧

^ a b c d e 田野村忠温「「科学」の語史 : 漸次的・段階的変貌と普及の様相 」『大阪大学大学院文学研究科紀要』第56巻、2016年3月31日、123-181頁、doi :10.18910/56924 、 オリジナル の2020年11月13日時点におけるアーカイブ、2024年12月26日 閲覧

^ 林美茂、趙敏「Philosophyの訳語をめぐる中江兆民の立場に関する一考察 」『文明21』第50巻、愛知大学国際コミュニケーション学会、2023年3月20日、63-83頁、ISSN 13444220 、NCID AA11306460 、2024年12月27日 閲覧 ^ 佐々木力 『科学論入門』岩波書店 〈岩波新書 〉、1996年8月21日、2-3頁。ISBN 9784004304579 。 ^ "Science" . Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary . 2019年9月1日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2011年10月16日閲覧 。^ Vaan, Michiel de [in 英語] (2008). "sciō" . Etymological Dictionary of Latin and the other Italic Languages . Indo-European Etymological Dictionary . p. 545. ISBN 978-90-04-16797-1 ^ Cahan, David (2003). From natural philosophy to the sciences: writing the history of nineteenth-century science . University of Chicago Press. pp. 3–15. ISBN 0-226-08927-4 ^ "scientist" . Oxford English Dictionary Oxford University Press . September 2005.(要購読、またはイギリス公立図書館への会員加入 。) ^ Ross, Sydney (1962). “Scientist: The story of a word”. Annals of Science 18 (2): 65–85. doi :10.1080/00033796200202722 . ^ Carruthers, Peter (2002-05-02), Carruthers, Peter; Stich, Stephen; Siegal, Michael, eds., “The roots of scientific reasoning: infancy, modularity and the art of tracking”, The Cognitive Basis of Science (Cambridge University Press): pp. 73–96, doi :10.1017/cbo9780511613517.005 , ISBN 978-0-521-81229-0 ^ Lombard, Marlize; Gärdenfors, Peter (2017). “Tracking the Evolution of Causal Cognition in Humans”. Journal of Anthropological Sciences 95 (95): 219–234. doi :10.4436/JASS.95006 . ISSN 1827-4765 . PMID 28489015 . ^ Graeber, David; Wengrow, David (2021). The Dawn of Everything . p. 248 ^ Budd, Paul; Taylor, Timothy (1995). “The Faerie Smith Meets the Bronze Industry: Magic Versus Science in the Interpretation of Prehistoric Metal-Making”. World Archaeology 27 (1): 133–143. doi :10.1080/00438243.1995.9980297 . JSTOR 124782 . ^ Tuomela, Raimo (1987). “Science, Protoscience, and Pseudoscience”. Rational Changes in Science . Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science. 98 . Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 83–101. doi :10.1007/978-94-009-3779-6_4 . ISBN 978-94-010-8181-8 ^ Smith, Pamela H. (2009). “Science on the Move: Recent Trends in the History of Early Modern Science”. Renaissance Quarterly 62 (2): 345–375. doi :10.1086/599864 . PMID 19750597 . ^ Fleck, Robert (2021年3月). “Fundamental Themes in Physics from the History of Art”. Physics in Perspective 23 (1): 25–48. Bibcode : 2021PhP....23...25F . doi :10.1007/s00016-020-00269-7 . ISSN 1422-6944 . ^ Scott, Colin (2011). "Science for the West, Myth for the Rest?". In Harding, Sandra (ed.). The Postcolonial Science and Technology Studies Reader . Durham, NC: Duke University Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-8223-4936-5 JSTOR j.ctv11g96cc.16 。 ^ Dear, Peter (2012). “Historiography of Not-So-Recent Science”. History of Science 50 (2): 197–211. doi :10.1177/007327531205000203 . ^ Rochberg, Francesca (2011). “Ch.1 Natural Knowledge in Ancient Mesopotamia”. In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter. Wrestling with Nature: From Omens to Science . University of Chicago Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0 ^ Krebs, Robert E. (2004). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance . Greenwood Publishing Group . p. 127. ISBN 978-0313324338 ^ Erlich, Ḥaggai ; Gershoni, Israel (2000). The Nile: Histories, Cultures, Myths ISBN 978-1-55587-672-2 . https://books.google.com/books?id=LcsJosc239YC&q=egyptian%20geometry%20Nile&pg=PA80 2020年1月9日 閲覧 ^ “Telling Time in Ancient Egypt ”. The Met's Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . 2022年3月3日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2022年5月27日 閲覧。 ^ a b c McIntosh, Jane R. (2005). Ancient Mesopotamia: New Perspectives ISBN 978-1-57607-966-9 . https://books.google.com/books?id=9veK7E2JwkUC&q=science+in+ancient+Mesopotamia 2020年10月20日 閲覧。

^ Aaboe, Asger (1974-05-02). “Scientific Astronomy in Antiquity”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 276 (1257): 21–42. Bibcode : 1974RSPTA.276...21A . doi :10.1098/rsta.1974.0007 . JSTOR 74272 . ^ Biggs, R. D. (2005). “Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health in Ancient Mesopotamia”. Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies 19 (1): 7–18. ^ Lehoux, Daryn (2011). “2. Natural Knowledge in the Classical World”. In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter. Wrestling with Nature: From Omens to Science . University of Chicago Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0 ^ An account of the pre-Socratic use of the concept of φύσις may be found in Naddaf, Gerard (2006). The Greek Concept of Nature . SUNY Press, Ducarme, Frédéric; Couvet, Denis (2020). “What does 'nature' mean?” . Palgrave Communications Springer Nature ) 6 (14). doi :10.1057/s41599-020-0390-y . オリジナル の2023-08-16時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20230816053756/https://hal.science/hal-02554932/file/s41599-020-0390-y.pdf 2023年8月16日 閲覧。 nature is used, as confirmed by Guthrie, W. K. C.. Presocratic Tradition from Parmenides to Democritus none History of Greek Philosophy ), Cambridge University Press, 1965.

^ Strauss, Leo; Gildin, Hilail (1989). “Progress or Return? The Contemporary Crisis in Western Education” . An Introduction to Political Philosophy: Ten Essays by Leo Strauss . Wayne State University Press . p. 209. ISBN 978-0814319024 . https://books.google.com/books?id=cpx2j0TumyIC 2022年5月30日 閲覧。 ^ O'Grady, Patricia F. (2016). Thales of Miletus: The Beginnings of Western Science and Philosophy ISBN 978-0-7546-0533-1 . https://books.google.com/books?id=ZTUlDwAAQBAJ&q=Thales+of+Miletus+first+scientist&pg=PA245 2020年10月20日 閲覧。 ^ a b Burkert, Walter (1972-06-01). Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism ISBN 978-0-674-53918-1 . https://books.google.com/books?id=0qqp4Vk1zG0C&q=Pythagoreanism

^ Pullman, Bernard (1998). The Atom in the History of Human Thought Bibcode : 1998ahht.book.....P . ISBN 978-0-19-515040-7 . https://books.google.com/books?id=IQs5hur-BpgC&q=Leucippus+Democritus+atom&pg=PA56 2020年10月20日 閲覧。 ^ Cohen, Henri; Lefebvre, Claire, eds (2017). Handbook of Categorization in Cognitive Science ISBN 978-0-08-101107-2 . https://books.google.com/books?id=zIrCDQAAQBAJ&q=Leucippus+Democritus+atom&pg=PA427 2020年10月20日 閲覧。 ^ Lucretius (fl. 1st cenruty BCE) De rerum natura ^ Margotta, Roberto (1968). The Story of Medicine Golden Press . https://books.google.com/books?id=vFZrAAAAMAAJ 2020年11月18日 閲覧。 ^ Touwaide, Alain (2005). Glick, Thomas F.; Livesey, Steven; Wallis, Faith. eds. Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia ISBN 978-0-415-96930-7 . https://books.google.com/books?id=77y2AgAAQBAJ&q=Hippocrates+medical+science&pg=PA224 2020年10月20日 閲覧。 ^ Leff, Samuel; Leff, Vera (1956). From Witchcraft to World Health . https://books.google.com/books?id=HjNrAAAAMAAJ 2020年8月23日 閲覧。 ^ “Plato, Apology ”. p. 17. 2018年1月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2017年11月1日 閲覧。 ^ “Plato, Apology ”. p. 27. 2018年1月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2017年11月1日 閲覧。 ^ Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics オリジナル の2012-03-17時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20120317140402/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc= 2010年9月22日 閲覧。 ^ a b McClellan, James E. III; Dorn, Harold (2015). Science and Technology in World History: An Introduction ISBN 978-1-4214-1776-9 . https://books.google.com/books?id=ah1ECwAAQBAJ&q=Aristarchus+heliocentrism&pg=PA99 2020年10月20日 閲覧。

^ Graßhoff, Gerd (1990). The History of Ptolemy's Star Catalogue . Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. 14 . New York: Springer. doi :10.1007/978-1-4612-4468-4 . ISBN 978-1-4612-8788-9 ^ Hoffmann, Susanne M. (2017) (ドイツ語). Hipparchs Himmelsglobus . Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. Bibcode : 2017hihi.book.....H . doi :10.1007/978-3-658-18683-8 . ISBN 978-3-658-18682-1 ^ Edwards, C. H. Jr. (1979). The Historical Development of the Calculus ISBN 978-0-387-94313-8 . https://books.google.com/books?id=ilrlBwAAQBAJ&q=Archimedes+calculus&pg=PA75 2020年10月20日 閲覧。 ^ Lawson, Russell M. (2004). Science in the Ancient World: An Encyclopedia ISBN 978-1-85109-539-1 . https://books.google.com/books?id=1AY1ALzh9V0C&q=Pliny+the+Elder+encyclopedia&pg=PA190 2020年10月20日 閲覧。 ^ Murphy, Trevor Morgan (2004). Pliny the Elder's Natural History: The Empire in the Encyclopedia ISBN 978-0-19-926288-5 . https://books.google.com/books?id=6NC_T_tG9lQC&q=Pliny+the+Elder+encyclopedia 2020年10月20日 閲覧。 ^ Doody, Aude (2010). Pliny's Encyclopedia: The Reception of the Natural History ISBN 978-1-139-48453-4 . https://books.google.com/books?id=YoEhAwAAQBAJ&q=Pliny+the+Elder+encyclopedia 2020年10月20日 閲覧。 ^ Conner, Clifford D. (2005). A People's History of Science: Miners, Midwives, and "Low Mechanicks" . New York: Nation Books. pp. 72–74. ISBN 1-56025-748-2 ^ Grant, Edward (1996). The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages: Their Religious, Institutional and Intellectual Contexts ISBN 978-0-521-56762-6 . https://books.google.com/books?id=YyvmEyX6rZgC 2018年11月9日 閲覧。 ^ Wildberg, Christian (1 May 2018). "Philoponus" . In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2019年8月22日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2018年5月1日閲覧 。 ^ Falcon, Andrea (2019). "Aristotle on Causality" . In Zalta, Edward (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2020年10月9日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2020年10月3日閲覧 。 ^ Grant, Edward (2007). “Islam and the eastward shift of Aristotelian natural philosophy” . A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century . Cambridge University Press. pp. 62 –67. ISBN 978-0-521-68957-1 . https://archive.org/details/historynaturalph00gran ^ Fisher, W. B. (1968–1991). The Cambridge history of Iran . Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6 ^ "Bayt al-Hikmah" . Encyclopædia Britannica . 2016年11月4日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2016年11月3日閲覧 。^ Hossein Nasr, Seyyed , ed (2001). History of Islamic Philosophy . Routledge. pp. 165–167. ISBN 978-0415259347 ^ a b Smith, A. Mark (2001). Alhacen's Theory of Visual Perception: A Critical Edition, with English Translation and Commentary, of the First Three Books of Alhacen's De Aspectibus, the Medieval Latin Version of Ibn al-Haytham's Kitāb al-Manāẓir, 2 vols . Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 91 . Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society . ISBN 978-0-87169-914-5

^ Toomer, G. J. (1964). “Reviewed work: Ibn al-Haythams Weg zur Physik, Matthias Schramm”. Isis 55 (4): 463–465. doi :10.1086/349914 . JSTOR 228328 . ^ Cohen, H. Floris (2010). “Greek nature knowledge transplanted: The Islamic world”. How modern science came into the world. Four civilizations, one 17th-century breakthrough (2nd ed.). Amsterdam University Press. pp. 99–156. ISBN 978-90-8964-239-4 ^ Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures 155 –156. Bibcode : 2008ehst.book.....S . ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2 . https://archive.org/details/encyclopaediahis00seli ^ Russell, Josiah C. (1959). “Gratian, Irnerius, and the Early Schools of Bologna”. The Mississippi Quarterly 12 (4): 168–188. JSTOR 26473232 . "Perhaps even as early as 1088 (the date officially set for the founding of the University)" ^ "St. Albertus Magnus" . Encyclopædia Britannica . 2017年10月28日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2017年10月27日閲覧 。^ Numbers, Ronald (2009). Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and Religion ISBN 978-0-674-03327-6 . http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674057418 2018年3月27日 閲覧。 ^ a b Smith, A. Mark (1981). “Getting the Big Picture in Perspectivist Optics”. Isis 72 (4): 568–589. doi :10.1086/352843 . JSTOR 231249 . PMID 7040292 .

^ Goldstein, Bernard R. (2016). “Copernicus and the Origin of his Heliocentric System” . Journal for the History of Astronomy 33 (3): 219–235. doi :10.1177/002182860203300301 . オリジナル の2020-04-12時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20200412211013/http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e610/194b7b608cab49e034a542017213d827fb70.pdf 2020年4月12日 閲覧。 ^ Cohen, H. Floris (2010). “Greek nature knowledge transplanted and more: Renaissance Europe”. How modern science came into the world. Four civilizations, one 17th-century breakthrough (2nd ed.). Amsterdam University Press. pp. 99–156. ISBN 978-90-8964-239-4 ^ Koestler, Arthur (1990). The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe 1 . ISBN 0-14-019246-8 . https://archive.org/details/sleepwalkershist00koes_0/page/1 ^ van Helden, Al (1995年). “Pope Urban VIII ”. The Galileo Project . 2016年11月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2016年11月3日 閲覧。 ^ Gingerich, Owen (1975). “Copernicus and the Impact of Printing”. Vistas in Astronomy 17 (1): 201–218. Bibcode : 1975VA.....17..201G . doi :10.1016/0083-6656(75)90061-6 . ^ Zagorin, Perez (1998). Francis Bacon . Princeton University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-691-00966-7 ^ Davis, Philip J.; Hersh, Reuben (1986). Descartes' Dream: The World According to Mathematics . Cambridge, MA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich ^ Gribbin, John (2002). Science: A History 1543–2001 . Allen Lane. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-7139-9503-9 . "Although it was just one of the many factors in the Enlightenment, the success of Newtonian physics in providing a mathematical description of an ordered world clearly played a big part in the flowering of this movement in the eighteenth century" ^ “Gottfried Leibniz – Biography ”. Maths History . 2017年7月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2021年3月2日 閲覧。 ^ Freudenthal, Gideon; McLaughlin, Peter (2009-05-20). The Social and Economic Roots of the Scientific Revolution: Texts by Boris Hessen and Henryk Grossmann ISBN 978-1-4020-9604-4 . https://books.google.com/books?id=PgmbZIybuRoC&pg=PA162 2018年7月25日 閲覧。 ^ Encyclopedia of the Renaissance ISBN 978-0816013159 . https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofre0000unse_d0p5 ^ van Horn Melton, James (2001). The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe doi :10.1017/CBO9780511819421 . ISBN 978-0511819421 . https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/rise-of-the-public-in-enlightenment-europe/BA532085A260114CD430D9A059BD96EF 2022年5月27日 閲覧。 ^ “The Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment (1500–1780) ”. 2024年1月14日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2024年1月29日 閲覧。 ^ "Scientific Revolution" . Encyclopædia Britannica . 2019年5月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2024年1月29日閲覧 。^ Madigan, M., ed (2006). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0131443297 ^ Guicciardini, N. (1999). Reading the Principia: The Debate on Newton's Methods for Natural Philosophy from 1687 to 1736 ISBN 978-0521640664 . https://archive.org/details/readingprincipia0000guic ^ Olby, R. C.; Cantor, G. N.; Christie, J. R. R.; Hodge, M. J. S. (1990). Companion to the History of Modern Science . London: Routledge. p. 265 ^ Darrigol, Olivier (2000). Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einstein ISBN 0198505949 . https://archive.org/details/electrodynamicsf0000darr ^ Calisher, CH (2007). “Taxonomy: what's in a name? Doesn't a rose by any other name smell as sweet?” . Croatian Medical Journal 48 (2): 268–270. PMC 2080517 . PMID 17436393 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2080517/ . ^ Magnusson, Magnus (2003年11月10日). “Review of James Buchan, Capital of the Mind: how Edinburgh Changed the World ”. New Statesman . 2011年6月6日時点のオリジナル よりアーカイブ。2014年4月27日 閲覧。 ^ Swingewood, Alan (1970). “Origins of Sociology: The Case of the Scottish Enlightenment”. The British Journal of Sociology 21 (2): 164–180. JSTOR 588406 . ^ Fry, Michael (1992). Adam Smith's Legacy: His Place in the Development of Modern Economics Paul Samuelson , Lawrence Klein , Franco Modigliani , James M. Buchanan , Maurice Allais , Theodore Schultz , Richard Stone , James Tobin , Wassily Leontief , Jan Tinbergen . Routledge . ISBN 978-0-415-06164-3 . https://archive.org/details/adamsmithslegacy0000unse ^ Lightman, Bernard (2011). “13. Science and the Public”. In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter. Wrestling with Nature: From Omens to Science . University of Chicago Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0 ^ Leahey, Thomas Hardy (2018). “The psychology of consciousness”. A History of Psychology: From Antiquity to Modernity (8th ed.). New York: Routledge. pp. 219–253. ISBN 978-1-138-65242-2 ^ Padian, Kevin (2008). “Darwin's enduring legacy”. Nature 451 (7179): 632–634. Bibcode : 2008Natur.451..632P . doi :10.1038/451632a . PMID 18256649 . ^ Henig, Robin Marantz (2000). The monk in the garden: the lost and found genius of Gregor Mendel, the father of genetics . https://archive.org/details/monkingardenlost00heni ^ Miko, Ilona (2008). “Gregor Mendel's principles of inheritance form the cornerstone of modern genetics. So just what are they?” . Nature Education 1 (1): 134. オリジナル の2019-07-19時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20190719224056/http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/gregor-mendel-and-the-principles-of-inheritance-593 2021年5月9日 閲覧。 ^ Rocke, Alan J. (2005). “In Search of El Dorado: John Dalton and the Origins of the Atomic Theory”. Social Research 72 (1): 125–158. doi :10.1353/sor.2005.0003 . JSTOR 40972005 . ^ a b Reichl, Linda (1980). A Modern Course in Statistical Physics . Edward Arnold. ISBN 0-7131-2789-9

^ Rao, Y. V. C. (1997). Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics . Universities Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-81-7371-048-3 ^ Heidrich, M. (2016). “Bounded energy exchange as an alternative to the third law of thermodynamics”. Annals of Physics 373 : 665–681. Bibcode : 2016AnPhy.373..665H . doi :10.1016/j.aop.2016.07.031 . ^ Mould, Richard F. (1995). A century of X-rays and radioactivity in medicine: with emphasis on photographic records of the early years (Reprint. with minor corr ed.). Bristol: Inst. of Physics Publ.. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7503-0224-1 ^ Estreicher, Tadeusz (1938). “Curie, Maria ze Skłodowskich” (ポーランド語). Polski słownik biograficzny, vol. 4 . p. 113 ^ Thomson, J. J. (1897). “Cathode Rays”. Philosophical Magazine 44 (269): 293–316. doi :10.1080/14786449708621070 . ^ Goyotte, Dolores (2017). “The Surgical Legacy of World War II. Part II: The age of antibiotics” . The Surgical Technologist 109 : 257–264. オリジナル の2021-05-05時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20210505180530/https://www.ast.org/ceonline/articles/402/files/assets/common/downloads/publication.pdf 2021年1月8日 閲覧。 ^ Erisman, Jan Willem; Sutton, M. A.; Galloway, J.; Klimont, Z.; Winiwarter, W. (2008年10月). “How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world” . Nature Geoscience 1 (10): 636–639. Bibcode : 2008NatGe...1..636E . doi :10.1038/ngeo325 . オリジナル の2010-07-23時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20100723223052/http://www.physics.ohio-state.edu/~wilkins/energy/Resources/Essays/ngeo325.pdf.xpdf 2010年10月22日 閲覧。 ^ Emmett, Robert; Zelko, Frank (2014). “Minding the Gap: Working Across Disciplines in Environmental Studies” . Environment & Society Portal . RCC Perspectives no. 2. doi :10.5282/rcc/6313 . オリジナル の2022-01-21時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20220121054306/https://www.environmentandsociety.org/perspectives/2014/2/minding-gap-working-across-disciplines-environmental-studies . ^ Furner, Jonathan (2003-06-01). “Little Book, Big Book: Before and After Little Science, Big Science: A Review Article, Part I”. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 35 (2): 115–125. doi :10.1177/0961000603352006 . ^ Kraft, Chris ; Schefter, James (2001). Flight: My Life in Mission Control ISBN 0-525-94571-7 . https://archive.org/details/flight00chri ^ Kahn, Herman (1962). Thinking about the Unthinkable . Horizon ^ Shrum, Wesley (2007). Structures of scientific collaboration . Joel Genuth, Ivan Chompalov. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-28358-8 ^ Rosser, Sue V. (2012-03-12). Breaking into the Lab: Engineering Progress for Women in Science . New York University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8147-7645-2 ^ Penzias, A. A. (2006). “The origin of elements” . Science (Nobel Foundation ) 205 (4406): 549–554. doi :10.1126/science.205.4406.549 . PMID 17729659 . オリジナル の2011-01-17時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20110117225210/http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1978/penzias-lecture.pdf 2006年10月4日 閲覧。 ^ Weinberg, S. (1972). Gravitation and Cosmology 464–495 . ISBN 978-0-471-92567-5 . https://archive.org/details/gravitationcosmo00stev_0/page/495 ^ “Apollo 11 - NASA ” (英語). NASA 2024年12月28日 閲覧。 ^ Chelsea Gohd (2019年7月16日). “Apollo 11 Turns 50: A Complete Guide to the Historic Moon Mission ” (英語). Space.com 2024年12月28日 閲覧。 ^ Futuyma, Douglas J.; Kirkpatrick, Mark (2017). “Chapter 1: Evolutionary Biology”. Evolution (4th ed.). Sinauer. pp. 3–26. ISBN 978-1605356051 ^ Miller, Arthur I. (1981). Albert Einstein's special theory of relativity. Emergence (1905) and early interpretation (1905–1911) . Reading: Addison–Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-04679-3 ^ ter Haar, D. (1967). The Old Quantum Theory 206 . ISBN 978-0-08-012101-7 . https://archive.org/details/oldquantumtheory0000haar ^ von Bertalanffy, Ludwig (1972). “The History and Status of General Systems Theory”. The Academy of Management Journal 15 (4): 407–426. JSTOR 255139 . ^ Naidoo, Nasheen; Pawitan, Yudi; Soong, Richie; Cooper, David N.; Ku, Chee-Seng (2011年10月). “Human genetics and genomics a decade after the release of the draft sequence of the human genome” . Human Genomics 5 (6): 577–622. doi :10.1186/1479-7364-5-06-577 . PMC 3525251 . PMID 22155605 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3525251/ . ^ Rashid, S. Tamir; Alexander, Graeme J. M. (2013年3月). “Induced pluripotent stem cells: from Nobel Prizes to clinical applications”. Journal of Hepatology 58 (3): 625–629. doi :10.1016/j.jhep.2012.10.026 . ISSN 1600-0641 . PMID 23131523 . ^ O'Luanaigh, C. (14 March 2013). "New results indicate that new particle is a Higgs boson" (Press release). CERN . 2015年10月20日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2013年10月9日閲覧 。 ^ Abbott, B. P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T. D.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P. et al. (2017). “Multi-messenger Observations of a Binary Neutron Star Merger”. The Astrophysical Journal 848 (2): L12. arXiv :1710.05833 . Bibcode : 2017ApJ...848L..12A . doi :10.3847/2041-8213/aa91c9 . ^ Cho, Adrian (2017). “Merging neutron stars generate gravitational waves and a celestial light show”. Science . doi :10.1126/science.aar2149 . ^ “Media Advisory: First Results from the Event Horizon Telescope to be Presented on April 10th ”. Event Horizon Telescope (2019年4月20日). 2019年4月20日時点のオリジナル よりアーカイブ。2021年9月21日 閲覧。 ^ “Scientific Method: Relationships Among Scientific Paradigms” . Seed Magazine . (2007-03-07). オリジナル の2016-11-01時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20161101001155/http://seedmagazine.com/content/article/scientific_method_relationships_among_scientific_paradigms/ 2016年11月4日 閲覧。 ^ Bunge, Mario Augusto (1998). Philosophy of Science: From Problem to Theory . Transaction. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7658-0413-6 ^ a b Popper, Karl R. (2002a). “A survey of some fundamental problems” . The Logic of Scientific Discovery . New York: Routledge. pp. 3 –26. ISBN 978-0-415-27844-7 . https://archive.org/details/logicscientificd00popp_574

^ Gauch, Hugh G. Jr. (2003). “Science in perspective” . Scientific Method in Practice . Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–73. ISBN 978-0-521-01708-4 . https://books.google.com/books?id=iVkugqNG9dAC&pg=PA71 2018年9月3日 閲覧。 ^ Oglivie, Brian W. (2008). “Introduction”. The Science of Describing: Natural History in Renaissance Europe (Paperback ed.). University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-0-226-62088-6 ^ “Formal Sciences: Washington and Lee University ”. Washington and Lee University . 2021年5月14日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2021年5月14日 閲覧。 “A "formal science" is an area of study that uses formal systems to generate knowledge such as in Mathematics and Computer Science. Formal sciences are important subjects because all of quantitative science depends on them.” ^ "Formal system" . Encyclopædia Britannica . 2008年4月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2022年5月30日閲覧 。^ Tomalin, Marcus (2006). Linguistics and the Formal Sciences ^ Löwe, Benedikt (2002). “The Formal Sciences: Their Scope, Their Foundations, and Their Unity”. Synthese 133 (1/2): 5–11. doi :10.1023/a:1020887832028 . ^ Bill, Thompson (2007). “2.4 Formal Science and Applied Mathematics”. The Nature of Statistical Evidence . Lecture Notes in Statistics. 189 . Springer. p. 15 ^ Bishop, Alan (1991). “Environmental activities and mathematical culture” . Mathematical Enculturation: A Cultural Perspective on Mathematics Education . Norwell, MA: Kluwer. pp. 20–59. ISBN 978-0-7923-1270-3 . https://books.google.com/books?id=9AgrBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA54 2018年3月24日 閲覧。 ^ Bunge, Mario (1998). “The Scientific Approach”. Philosophy of Science: Volume 1, From Problem to Theory . 1 (revised ed.). New York: Routledge. pp. 3–50. ISBN 978-0-7658-0413-6 ^ Mujumdar, Anshu Gupta; Singh, Tejinder (2016). “Cognitive science and the connection between physics and mathematics”. Trick or Truth?: The Mysterious Connection Between Physics and Mathematics . The Frontiers Collection. Switzerland: Springer. pp. 201–218. ISBN 978-3-319-27494-2 ^ “About the Journal ”. Journal of Mathematical Physics オリジナル よりアーカイブ。2006年10月3日 閲覧。 ^ Restrepo, G. (2016). “Mathematical chemistry, a new discipline” . Essays in the philosophy of chemistry . New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 332–351. ISBN 978-0-19-049459-9 . https://global.oup.com/academic/product/essays-in-the-philosophy-of-chemistry-9780190494599?cc=de&lang=en& ^ “What is mathematical biology ”. Centre for Mathematical Biology, University of Bath. 2018年9月23日時点のオリジナル よりアーカイブ。2018年6月7日 閲覧。 ^ Varian, Hal (1997). “What Use Is Economic Theory?”. Is Economics Becoming a Hard Science? . Edward Elgar Pre-publication . Archived 2006-06-25 at the Wayback Machine .. Retrieved 2008-04-01.^ Johnson, Tim (2009-09-01). “What is financial mathematics?” . +Plus Magazine . オリジナル の2022-04-08時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20220408231344/https://plus.maths.org/content/what-financial-mathematics 2021年3月1日 閲覧。 ^ Abraham, Reem Rachel (2004). “Clinically oriented physiology teaching: strategy for developing critical-thinking skills in undergraduate medical students”. Advances in Physiology Education 28 (3): 102–104. doi :10.1152/advan.00001.2004 . PMID 15319191 . ^ Davis, Bernard D. (2000年3月). “Limited scope of science” . Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 64 (1): 1–12. doi :10.1128/MMBR.64.1.1-12.2000 . PMC 98983 . PMID 10704471 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC98983/ none Davis, Bernard (Mar 2000). “The scientist's world” . Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 64 (1): 1–12. doi :10.1128/MMBR.64.1.1-12.2000 . PMC 98983 . PMID 10704471 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC98983/ . ^ McCormick, James (2001). “Scientific medicine—fact of fiction? The contribution of science to medicine” . Occasional Paper (Royal College of General Practitioners) (80): 3–6. PMC 2560978 . PMID 19790950 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2560978/ . ^ "Engineering" . Cambridge Dictionary . Cambridge University Press. 2019年8月19日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2021年3月25日閲覧 。^ Brooks, Harvey (1994-09-01). “The relationship between science and technology” . Research Policy . Special Issue in Honor of Nathan Rosenberg 23 (5): 477–486. doi :10.1016/0048-7333(94)01001-3 . ISSN 0048-7333 . オリジナル の2022-12-30時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20221230224402/https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/files/publication/sciencetechnology.pdf 2022年10月14日 閲覧。 ^ Firth, John (2020). “Science in medicine: when, how, and what”. Oxford textbook of medicine . Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-874669-0 ^ Saunders, J. (2000年6月). “The practice of clinical medicine as an art and as a science” . Med Humanit 26 (1): 18–22. doi :10.1136/mh.26.1.18 . PMC 1071282 . PMID 12484313 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1071282/ . ^ Breznau, Nate (2022). “Integrating Computer Prediction Methods in Social Science: A Comment on Hofman et al. (2021)” . Social Science Computer Review 40 (3): 844–853. doi :10.1177/08944393211049776 . オリジナル の2024-04-29時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20240429040922/https://osf.io/adxb3/download 2023年8月16日 閲覧。 ^ Hofman, Jake M.; Watts, Duncan J. ; Athey, Susan ; Garip, Filiz; Griffiths, Thomas L. ; Kleinberg, Jon ; Margetts, Helen ; Mullainathan, Sendhil et al. (2021年7月). “Integrating explanation and prediction in computational social science” . Nature 595 (7866): 181–188. Bibcode : 2021Natur.595..181H . doi :10.1038/s41586-021-03659-0 . ISSN 1476-4687 . PMID 34194044 . オリジナル の2021-09-25時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20210925074416/https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03659-0 2021年9月25日 閲覧。 ^ Nissani, M. (1995). “Fruits, Salads, and Smoothies: A Working definition of Interdisciplinarity”. The Journal of Educational Thought 29 (2): 121–128. JSTOR 23767672 . ^ Moody, G. (2004). Digital Code of Life: How Bioinformatics is Revolutionizing Science, Medicine, and Business ISBN 978-0-471-32788-2 . https://archive.org/details/digitalcodeoflif0000mood ^ Ausburg, Tanya (2006). Becoming Interdisciplinary: An Introduction to Interdisciplinary Studies (2nd ed.). New York: Kendall/Hunt Publishing ^ 合志陽一「基礎研究と応用研究|国環研ニュース 17巻|国立環境研究所 」『国立環境研究所 』。2024年12月22日閲覧 。 ^ “What is basic research? ”. National Science Foundation . 2024年12月22日 閲覧。 ^ a b di Francia, Giuliano Toraldo (1976). “The method of physics”. The Investigation of the Physical World . Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–52. ISBN 978-0-521-29925-1 . "The amazing point is that for the first time since the discovery of mathematics, a method has been introduced, the results of which have an intersubjective value!"

^ Popper, Karl R. (2002e). “The problem of the empirical basis” . The Logic of Scientific Discovery . New York: Routledge. pp. 3 –26. ISBN 978-0-415-27844-7 . https://archive.org/details/logicscientificd00popp_574 ^ Diggle, Peter J. ; Chetwynd, Amanda G. (2011). Statistics and Scientific Method: An Introduction for Students and Researchers . Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199543182 ^ Wilson, Edward (1999). Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge . New York: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-679-76867-8 ^ Fara, Patricia (2009). “Decisions” . Science: A Four Thousand Year History . Oxford University Press. p. 408 . ISBN 978-0-19-922689-4 . https://archive.org/details/sciencefourthous00fara/page/306 ^ Aldrich, John (1995). “Correlations Genuine and Spurious in Pearson and Yule”. Statistical Science 10 (4): 364–376. doi :10.1214/ss/1177009870 . JSTOR 2246135 . ^ Nola, Robert; Irzik, Gürol (2005). Philosophy, science, education and culture . Science & technology education library. 28 . Springer. pp. 207–230. ISBN 978-1-4020-3769-6 ^ van Gelder, Tim (1999年). “"Heads I win, tails you lose": A Foray Into the Psychology of Philosophy ”. University of Melbourne. 2008年4月9日時点のオリジナル よりアーカイブ。2008年3月28日 閲覧。 ^ Pease, Craig (2006年9月6日). “Chapter 23. Deliberate bias: Conflict creates bad science ”. Science for Business, Law and Journalism . Vermont Law School. 2010年6月19日時点のオリジナル よりアーカイブ。2024年12月28日 閲覧。 ^ Shatz, David (2004). Peer Review: A Critical Inquiry . Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-1434-8 ^ Krimsky, Sheldon (2003). Science in the Private Interest: Has the Lure of Profits Corrupted the Virtue of Biomedical Research ISBN 978-0-7425-1479-9 . https://archive.org/details/scienceinprivate0000krim ^ Bulger, Ruth Ellen; Heitman, Elizabeth; Reiser, Stanley Joel (2002). The Ethical Dimensions of the Biological and Health Sciences (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00886-0 ^ Backer, Patricia Ryaby (2004年10月29日). “What is the scientific method? ”. San Jose State University. 2008年4月8日時点のオリジナル よりアーカイブ。2008年3月28日 閲覧。 ^ Ziman, John (1978c). “Common observation” . Reliable knowledge: An exploration of the grounds for belief in science . Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–76 . ISBN 978-0-521-22087-3 . https://archive.org/details/reliableknowledg00john/page/42 ^ Ziman, J. M. (1980). “The proliferation of scientific literature: a natural process”. Science 208 (4442): 369–371. Bibcode : 1980Sci...208..369Z . doi :10.1126/science.7367863 . PMID 7367863 . ^ “STM Global Brief 2021-Economics & Market Size” (英語). STM : 15. (2021). https://stm-assoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/2022_08_24_STM_White_Report_a4_v15.pdf . ^ Schooler, J. W. (2014). “Metascience could rescue the 'replication crisis'”. Nature 515 (7525): 9. Bibcode : 2014Natur.515....9S . doi :10.1038/515009a . PMID 25373639 . ^ Pashler, Harold; Wagenmakers, Eric Jan (2012). “Editors' Introduction to the Special Section on Replicability in Psychological Science: A Crisis of Confidence?”. Perspectives on Psychological Science 7 (6): 528–530. doi :10.1177/1745691612465253 . PMID 26168108 . ^ Ioannidis, John P. A.; Fanelli, Daniele; Dunne, Debbie Drake; Goodman, Steven N. (2015-10-02). “Meta-research: Evaluation and Improvement of Research Methods and Practices” . PLOS Biology 13 (10): –1002264. doi :10.1371/journal.pbio.1002264 . ISSN 1545-7885 . PMC 4592065 . PMID 26431313 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4592065/ . ^ Hansson, Sven Ove (3 September 2008). "Science and Pseudoscience" . In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Section 2: The "science" of pseudoscience. 2021年10月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2022年5月28日閲覧 。 ^ Shermer, Michael (1997). Why people believe weird things: pseudoscience, superstition, and other confusions of our time ISBN 978-0-7167-3090-3 . https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780965594875 ^ Feynman, Richard (1974年). “Cargo Cult Science ”. Center for Theoretical Neuroscience . Columbia University. 2005年3月4日時点のオリジナル よりアーカイブ。2016年11月4日 閲覧。 ^ Novella, Steven (2018). The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe: How to Know What's Really Real in a World Increasingly Full of Fake . Hodder & Stoughton. p. 162. ISBN 978-1473696419 ^ “Coping with fraud” . The COPE Report 1999 : 11–18. オリジナル の2007-09-28時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20070928151119/http://www.publicationethics.org.uk/reports/1999/1999pdf3.pdf 2011年7月21日 閲覧 ^ a b Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003c). “Induction and confirmation” . Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science . University of Chicago. pp. 39 –56. ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7 . https://archive.org/details/theoryrealityint00godf

^ Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003o). “Empiricism, naturalism, and scientific realism?” . Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science . University of Chicago. pp. 219 –232. ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7 . https://archive.org/details/theoryrealityint00godf ^ Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003b). “Logic plus empiricism” . Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science . University of Chicago. pp. 19 –38. ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7 . https://archive.org/details/theoryrealityint00godf ^ a b Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003d). “Popper: Conjecture and refutation” . Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science . University of Chicago. pp. 57 –74. ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7 . https://archive.org/details/theoryrealityint00godf

^ Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003g). “Lakatos, Laudan, Feyerabend, and frameworks” . Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science . University of Chicago. pp. 102 –121. ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7 . https://archive.org/details/theoryrealityint00godf ^ Popper, Karl (1972). Objective Knowledge ^ Newton-Smith, W. H. (1994). The Rationality of Science 30 . ISBN 978-0-7100-0913-5 . https://archive.org/details/rationalityofsci0000newt ^ Votsis, I. (2004). The Epistemological Status of Scientific Theories: An Investigation of the Structural Realist Account (PhD thesis). University of London, London School of Economics. p. 39. ^ Bird, Alexander (2013). "Thomas Kuhn" . In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . 2020年7月15日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2015年10月26日閲覧 。 ^ Kuhn, Thomas S. (1970). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions ISBN 978-0-226-45804-5 . オリジナル の2021-10-19時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20211019102817/https://philpapers.org/rec/KUHTSO-2 2022年5月30日 閲覧。 ^ Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2003). “Naturalistic philosophy in theory and practice” . Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science . University of Chicago. pp. 149 –162. ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7 . https://archive.org/details/theoryrealityint00godf ^ Brugger, E. Christian (2004). “Casebeer, William D. Natural Ethical Facts: Evolution, Connectionism, and Moral Cognition”. The Review of Metaphysics 58 (2). ^ Kornfeld, W.; Hewitt, C. E. (1981). “The Scientific Community Metaphor” . IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 11 (1): 24–33. doi :10.1109/TSMC.1981.4308575 . hdl :1721.1/5693 オリジナル の2016-04-08時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20160408100757/http://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/5693/AIM-641.pdf?sequence=2 2022年5月26日 閲覧。 ^ “Eusocial climbers ”. E. O. Wilson Foundation. 2019年4月27日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2018年9月3日 閲覧。 “But he's not a scientist, he's never done scientific research. My definition of a scientist is that you can complete the following sentence: 'he or she has shown that...'," Wilson says.” ^ “Our definition of a scientist ”. Science Council. 2019年8月23日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2018年9月7日 閲覧。 “A scientist is someone who systematically gathers and uses research and evidence, making a hypothesis and testing it, to gain and share understanding and knowledge.” ^ Cyranoski, David; Gilbert, Natasha; Ledford, Heidi; Nayar, Anjali ; Yahia, Mohammed (2011). “Education: The PhD factory”. Nature 472 (7343): 276–279. Bibcode : 2011Natur.472..276C . doi :10.1038/472276a . PMID 21512548 . ^ Cyranoski, David; Gilbert, Natasha; Ledford, Heidi; Nayar, Anjali; Yahia, Mohammed (2011). “Education: The PhD factory”. Nature 472 (7343): 276–279. Bibcode : 2011Natur.472..276C . doi :10.1038/472276a . PMID 21512548 . ^ Kwok, Roberta (2017). “Flexible working: Science in the gig economy”. Nature 550 (7677): 419–421. doi :10.1038/nj7677-549a . ^ Woolston, Chris (2007). “Many junior scientists need to take a hard look at their job prospects”. Nature 550 (7677): 549–552. doi :10.1038/nj7677-549a . ^ Lee, Adrian; Dennis, Carina; Campbell, Phillip (2007). “Graduate survey: A love–hurt relationship”. Nature 550 (7677): 549–552. doi :10.1038/nj7677-549a . ^ Whaley, Leigh Ann (2003). Women's History as Scientists . Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO ^ Spanier, Bonnie (1995). “From Molecules to Brains, Normal Science Supports Sexist Beliefs about Difference”. Im/partial Science: Gender Identity in Molecular Biology . Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20968-9 ^ Parrott, Jim (2007年8月9日). “Chronicle for Societies Founded from 1323 to 1599 ”. Scholarly Societies Project. 2014年1月6日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2007年9月11日 閲覧。 ^ “The Environmental Studies Association of Canada – What is a Learned Society? ”. 2013年5月29日時点のオリジナル よりアーカイブ。2013年5月10日 閲覧。 ^ “Learned societies & academies ”. 2014年6月3日時点のオリジナル よりアーカイブ。2013年5月10日 閲覧。 ^ “Learned Societies, the key to realising an open access future? ”. Impact of Social Sciences . London School of Economics (2019年6月24日). 2023年2月5日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2023年1月22日 閲覧。 ^ “Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei ” (イタリア語) (2006年). 2010年2月28日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2007年9月11日 閲覧。 ^ “Prince of Wales opens Royal Society's refurbished building ”. The Royal Society (2004年7月7日). 2015年4月9日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2009年12月7日 閲覧。 ^ Meynell, G. G.. “The French Academy of Sciences, 1666–91: A reassessment of the French Académie royale des sciences under Colbert (1666–83) and Louvois (1683–91) ”. 2012年1月18日時点のオリジナル よりアーカイブ。2011年10月13日 閲覧。 ^ “Founding of the National Academy of Sciences ”. .nationalacademies.org. 2013年2月3日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2012年3月12日 閲覧。 ^ “The founding of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society (1911) ”. Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. 2022年3月2日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2022年5月30日 閲覧。 ^ “Introduction ”. Chinese Academy of Sciences . 2022年3月31日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2022年5月31日 閲覧。 ^ “Two main Science Councils merge to address complex global challenges ”. UNESCO (2018年7月5日). 2021年7月12日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2018年10月21日 閲覧。 ^ Stockton, Nick (2014年10月7日). “How did the Nobel Prize become the biggest award on Earth?” . Wired . オリジナル の2019年6月19日時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20190619044702/https://www.wired.com/2014/10/whats-nobel-prize-become-biggest-award-planet/ 2018年9月3日 閲覧。 ^ “Main Science and Technology Indicators – 2008-1 ”. OECD . 2010年2月15日時点のオリジナル よりアーカイブ。2024年12月28日 閲覧。 ^ OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2015: Innovation for growth and society doi :10.1787/sti_scoreboard-2015-en . ISBN 978-9264239784 . オリジナル の2022-05-25時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20220525063455/https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/oecd-science-technology-and-industry-scoreboard-2015_sti_scoreboard-2015-en 2022年5月28日 閲覧。 ^ Kevles, Daniel (1977). “The National Science Foundation and the Debate over Postwar Research Policy, 1942–1945”. Isis 68 (241): 4–26. doi :10.1086/351711 . PMID 320157 . ^ “Argentina, National Scientific and Technological Research Council (CONICET) ”. International Science Council . 2022年5月16日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2022年5月31日 閲覧。 ^ Innis, Michelle (2016年5月17日). “Australia to Lay Off Leading Scientist on Sea Levels” . The New York Times . ISSN 0362-4331 . オリジナル の2021年5月7日時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20210507080237/https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/18/world/australia/australia-to-lay-off-leading-scientist-on-sea-levels.html 2022年5月31日 閲覧。 ^ “Le CNRS recherche 10.000 passionnés du blob ” (フランス語). Le Figaro アーカイブ 。2022年5月31日 閲覧。 ^ Bredow, Rafaela von (2021年12月18日). “How a Prestigious Scientific Organization Came Under Suspicion of Treating Women Unequally” . Der Spiegel . ISSN 2195-1349 . オリジナル の2022年5月29日時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20220529004707/https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/how-a-prestigious-scientific-organization-came-under-suspicion-of-treating-women-unequally-a-96da63b5-19af-4fde-b044-445f9cfd6159 2022年5月31日 閲覧。 ^ “En espera de una "revolucionaria" noticia sobre Sagitario A*, el agujero negro supermasivo en el corazón de nuestra galaxia ” (スペイン語). ELMUNDO (2022年5月12日). 2022年5月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2022年5月31日 閲覧。 ^ Fletcher, Anthony C.; Bourne, Philip E. (2012-09-27). “Ten Simple Rules To Commercialize Scientific Research” . PLOS Computational Biology 8 (9): e1002712. Bibcode : 2012PLSCB...8E2712F . doi :10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002712 . ISSN 1553-734X . PMC 3459878 . PMID 23028299 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3459878/ . ^ Marburger, John Harmen III (2015-02-10). Science policy up close . Crease, Robert P.. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-41709-0 ^ Bush, Vannevar (1945年7月). “Science the Endless Frontier ”. National Science Foundation. 2016年11月7日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2016年11月4日 閲覧。 ^ Gauch, Hugh G. (2012). Scientific Method in Brief . New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–10. ISBN 9781107666726 ^ Benneworth, Paul; Jongbloed, Ben W. (2009-07-31). “Who matters to universities? A stakeholder perspective on humanities, arts and social sciences valorisation” . Higher Education 59 (5): 567–588. doi :10.1007/s10734-009-9265-2 . ISSN 0018-1560 . オリジナル の2023-10-24時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20231024214150/https://ris.utwente.nl/ws/files/47901538/Benneworth2010Who.pdf 2023年8月16日 閲覧。 ^ Dickson, David (2004年10月11日). “Science journalism must keep a critical edge ”. Science and Development Network. 2010年6月21日時点のオリジナル よりアーカイブ。2024年12月28日 閲覧。 ^ Mooney, Chris (Nov–Dec 2004). “Blinded By Science, How 'Balanced' Coverage Lets the Scientific Fringe Hijack Reality” . Columbia Journalism Review 43 (4). オリジナル の2010-01-17時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20100117181240/http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/intersection/2010/01/15/blinded-by-science-how-balanced-coverage-lets-the-scientific-fringe-hijack-reality/ 2008年2月20日 閲覧。 ^ McIlwaine, S.; Nguyen, D. A. (2005). “Are Journalism Students Equipped to Write About Science?” . Australian Studies in Journalism 14 : 41–60. オリジナル の2008-08-01時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20080801163322/http://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:8064 2008年2月20日 閲覧。 ^ “Popular science: Get the word out”. Nature 504 (7478): 177–179. (2013年12月). doi :10.1038/nj7478-177a . PMID 24312943 . ^ Wilde, Fran (2016年1月21日). “How Do You Like Your Science Fiction? Ten Authors Weigh In On 'Hard' vs. 'Soft' SF ”. Tor.com . 2019年4月4日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2019年4月4日 閲覧。^ “Majority in U.S. Says Public Health Benefits of COVID-19 Restrictions Worth the Costs, Even as Large Shares Also See Downsides ”. Pew Research Center Science & Society (2021年9月15日). 2022年8月9日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2022年8月4日 閲覧。 ^ Kennedy, Brian (2020年4月16日). “U.S. concern about climate change is rising, but mainly among Democrats ”. Pew Research Center . 2022年8月3日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2022年8月4日 閲覧。 ^ Philipp-Muller, Aviva; Lee, Spike W. S.; Petty, Richard E. (2022-07-26). “Why are people antiscience, and what can we do about it?” . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119 (30): e2120755119. Bibcode : 2022PNAS..11920755P . doi :10.1073/pnas.2120755119 . ISSN 0027-8424 . PMC 9335320 . PMID 35858405 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9335320/ . ^ Gauchat, Gordon William (2008). “A Test of Three Theories of Anti-Science Attitudes”. Sociological Focus 41 (4): 337–357. doi :10.1080/00380237.2008.10571338 . ^ “Climate Change Remains Top Global Threat Across 19-Country Survey ”. Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project (2022年8月31日). 2022年8月31日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ 。2022年9月5日 閲覧。 ^ McRaney, David (2022). How Minds Change: The Surprising Science of Belief, Opinion, and Persuasion . New York: Portfolio/Penguin. ISBN 978-0-593-19029-6 ^ McGreal, Chris (2021年10月26日). “Revealed: 60% of Americans say oil firms are to blame for the climate crisis” . The Guardian . オリジナル の2021年10月26日時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20211026122356/https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/oct/26/climate-change-poll-oil-gas-companies-environment . "Source: Guardian/Vice/CCN/YouGov poll. Note: ±4% margin of error." ^ Goldberg, Jeanne (2017). “The Politicization of Scientific Issues: Looking through Galileo's Lens or through the Imaginary Looking Glass” . Skeptical Inquirer 41 (5): 34–39. オリジナル の2018-08-16時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20180816182350/https://www.csicop.org/si/show/politicization_of_scientific_issues 2018年8月16日 閲覧。 ^ Bolsen, Toby; Druckman, James N. (2015). “Counteracting the Politicization of Science”. Journal of Communication (65): 746. ^ a b Freudenberg, William F.; Gramling, Robert; Davidson, Debra J. (2008). “Scientific Certainty Argumentation Methods (SCAMs): Science and the Politics of Doubt” . Sociological Inquiry 78 (1): 2–38. doi :10.1111/j.1475-682X.2008.00219.x . オリジナル の2020-11-26時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20201126214329/http://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/students/envs_5720/freudenberg_etal_2008.pdf 2020年4月12日 閲覧。

^ van der Linden, Sander; Leiserowitz, Anthony; Rosenthal, Seth; Maibach, Edward (2017). “Inoculating the Public against Misinformation about Climate Change” . Global Challenges 1 (2): 1. Bibcode : 2017GloCh...100008V . doi :10.1002/gch2.201600008 . PMC 6607159 . PMID 31565263 . オリジナル の2020-04-04時点におけるアーカイブ。. https://web.archive.org/web/20200404185312/https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/270860/global%20challenges.pdf?sequence=1 2019年8月25日 閲覧。