|

Al Smith

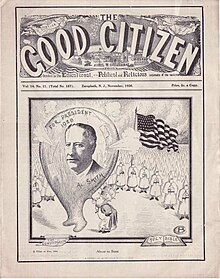

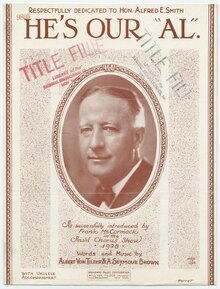

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was the 42nd governor of New York, serving from 1919 to 1920 and again from 1923 to 1928. He was the Democratic Party's presidential nominee in the 1928 presidential election, losing to Herbert Hoover of the Republican Party in a landslide. The son of an Irish-American mother and a Civil War–veteran Italian-American father, true surname Ferraro, Smith was raised on the Lower East Side of Manhattan near the Brooklyn Bridge. He resided in that neighborhood for his entire life. Although Smith remained personally untarnished by corruption, he—like many other New York Democrats—was linked to the notorious Tammany Hall political machine that controlled New York City politics during his era.[1] Smith served in the New York State Assembly from 1904 to 1915 and held the position of Speaker of the Assembly in 1913. Smith also served as sheriff of New York County from 1916 to 1917. He was first elected governor of New York in 1918, lost his 1920 bid for re-election, and was elected governor again in 1922, 1924, and 1926. Smith was the foremost urban leader of the efficiency movement in the United States and was noted for achieving a wide range of reforms as the New York governor in the 1920s. Smith was the first Roman Catholic to be nominated for president of the United States by a major party. His 1928 presidential candidacy mobilized both Catholic and anti-Catholic voters.[2] Many Protestants (including German Lutherans and Southern Baptists) feared his candidacy, believing that the Pope in Rome would dictate his policies. Smith was also a committed "wet" (i.e., an opponent of Prohibition); as New York governor, he had repealed the state's prohibition law. As a "wet", Smith attracted voters who wanted beer, wine, and liquor and did not like dealing with criminal bootleggers, along with voters who were outraged that new criminal gangs had taken over the streets in most large and medium-sized cities.[3] Incumbent Republican Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover was aided by national prosperity, the absence of American involvement in war, and anti-Catholic bigotry, and he defeated Smith in a landslide in 1928. Smith then entered business in New York City, and became involved in the construction and promotion of the Empire State Building. He sought the 1932 Democratic presidential nomination but was defeated by Franklin D. Roosevelt, his former ally and successor as governor of New York. During the Roosevelt presidency, Smith became an increasingly vocal opponent of Roosevelt's New Deal. Early life Smith was born at 174 South Street and raised in the Fourth Ward on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1873; he resided there for his entire life.[4] His mother, Catherine (née Mulvihill), was the daughter of Maria Marsh and Thomas Mulvihill, who were immigrants from County Westmeath, Ireland.[5] His father, baptised Joseph Alfred Smith in 1839, was the son of Emanuel Smith, an Italian marinaro (sailor).[citation needed] The elder Alfred Smith (Anglicized name for Alfredo Emanuele Ferraro) was the son of Italian and German[6][7] immigrants. He served with the 11th New York Fire Zouaves in the opening months of the Civil War. Smith grew up with his family struggling financially in the Gilded Age; New York City matured and completed major infrastructure projects. The Brooklyn Bridge was being constructed nearby. "The Brooklyn Bridge and I grew up together", Smith would later recall.[8] His four grandparents were of ethnic German, Irish as well as Italian ancestry,[9] but Smith identified more with the Irish-American community and became its leading spokesman in the 1920s. His father Alfred owned a small trucking firm, but died when Smith was 13. Aged 14, Smith had to drop out of St. James parochial school to help support the family, and worked at a fish market for seven years. Prior to dropping out of school, he served as an altar boy, and was strongly influenced by the Catholic priests he worked with.[10] He never attended high school or college, and claimed he learned about people by studying them at the Fulton Fish Market, where he worked for $12 per week. His acting skills made him a success on the amateur theater circuit. He became widely known, and developed the smooth oratorical style that characterized his political career. On May 6, 1900, Al Smith married Catherine Ann Dunn, with whom he had five children.[1] Political career In his political career, Smith built on his working-class beginnings, identifying himself with immigrants and campaigning as a man of the people. Although indebted to the Tammany Hall political machine (and particularly to its boss, "Silent" Charlie Murphy), he remained untarnished by corruption and worked for the passage of progressive legislation.[11] It was during his early unofficial jobs with Tammany Hall that he gained renown as an orator.[12] Smith's first political job was in 1895, as an investigator in the office of the Commissioner of Jurors as appointed by Tammany Hall. During his time as the Governor of New York, Smith became known as a progressive; David Farber wrote that "Smith became a strong and effective advocate of worker safety laws and championed, then and for years after, legislation aimed at giving workers more rights and protections against economic exploitation." He staunchly supported labor unions and pressed for protective legislation for the workers, stressing the need to expand the rights of working women in particular. A “New Era Progressive”, Smith advocated local governnment funded facilities and services such as hospitals, parks and schools in poor and working-class areas. Speaking of the role of the state in 1927, Smith said: "The State is a living force. It must have the ability to clothe itself with human understanding of the daily, living needs of those whom it is created to serve."[11] However, Smith envisioned a progressive vision based on state and local intervention, and decentralizing power to specific locales and communities. He was ambivalent with regard to federal economic intervention, which eventually led him to oppose the New Deal legislation.[13] State legislature Smith was first elected to the New York State Assembly (New York Co., 2nd D.) in 1904, and was repeatedly elected to office, serving through 1915.[10] After being approached by Frances Perkins, an activist to improve labor practices, Smith sought to improve the conditions of factory workers. Smith served as vice chairman of the state commission appointed to investigate factory conditions after 146 workers died in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. Meeting the families of the deceased Triangle factory workers left a strong impression on him. Together with Perkins and Robert F. Wagner, Smith crusaded against dangerous and unhealthy workplace conditions and championed corrective legislation.[12][14] The Commission, chaired by State Senator Robert F. Wagner, held a series of widely publicized investigations around the state, interviewing 222 witnesses and taking 3,500 pages of testimony. They hired field agents to do on-site inspections of factories. Starting with the issue of fire safety, they studied broader issues of the risks of injury in the factory environment. Their findings led to thirty-eight new laws regulating labor in New York State, and gave each of them a reputation as leading progressive reformers working on behalf of the working class. In the process, they changed Tammany's reputation from mere corruption to progressive endeavors to help the workers.[15] New York City's Fire Chief John Kenlon told the investigators that his department had identified more than 200 factories where conditions resulted in risk of a fire like that at the Triangle Factory.[16] The State Commission's reports led to the modernization of the state's labor laws, making New York State "one of the most progressive states in terms of labor reform."[17][18] New laws mandated better building access and egress, fireproofing requirements, the availability of fire extinguishers, the installation of alarm systems and automatic sprinklers, better eating and toilet facilities for workers, and limited the number of hours that women and children could work. In the years from 1911 to 1913, sixty of the sixty-four new laws recommended by the Commission were legislated with the support of Governor William Sulzer.[19] In 1911, the Democrats obtained a majority of seats in the State Assembly, and Smith became Majority Leader and Chairman of the Committee on Ways and Means. The following year, following the loss of the majority, he became the Minority Leader. When the Democrats reclaimed the majority after the next election, he was elected Speaker for the 1913 session. He became Minority Leader again in 1914 and 1915. In November 1915, he was elected Sheriff of New York County, New York. By now he was a leader of the Progressive movement in New York City and state. His campaign manager and top aide was Belle Moskowitz, a daughter of Jewish immigrants.[1] Governor (1919–1920, 1923–1928) After serving in the patronage-rich job of sheriff of New York County beginning in 1916, Smith was elected governor of New York in 1918 with the help of Tammany Boss Charles F. Murphy and James A. Farley, who brought Smith the upstate vote.[20] In 1919, Smith gave the famous speech "A man as low and mean as I can picture",[21] making a drastic break with publisher William Randolph Hearst. Hearst, known for his notoriously sensationalist and largely left-wing position in the state Democratic Party, was the leader of its populist wing in the city. He had combined with Tammany Hall in electing the local administration, and had attacked Smith for starving children by not reducing the cost of milk.[22] Smith lost his bid for re-election in the 1920 New York gubernatorial election, but was again elected governor in 1922, 1924 and 1926, with Farley managing his campaign. In his 1922 re-election, he embraced his position as an anti-prohibitionist. Smith offered alcohol to guests at the Executive Mansion in Albany, and repealed the state's Prohibition enforcement statute, the Mullan-Gage law.[23] As governor, Smith became known nationally as a progressive who sought to make government more efficient and more effective in meeting social needs. Smith's young assistant Robert Moses built the nation's first state park system and reformed the civil service, later gaining appointment as Secretary of State of New York. During Smith's time in office, New York strengthened laws governing workers' compensation, women's pensions and children and women's labor with the help of Frances Perkins, soon to be President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Labor Secretary.  1924 presidential electionIn 1924, Smith unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination for president, advancing the cause of civil liberty by decrying lynching and racial violence. Roosevelt delivered the nominating speech for Smith at the 1924 Democratic National Convention in which he saluted Smith as "the Happy Warrior of the political battlefield."[1] Smith represented the urban, east coast wing of the party as an anti-prohibition "wet" candidate, while his main rival for the nomination, President Woodrow Wilson's son-in-law William Gibbs McAdoo, a former Secretary of the Treasury, stood for the more rural tradition and prohibition "dry" candidacy.[24] The party was hopelessly split between the two. An increasingly chaotic convention balloted 100 times before both men accepted that neither would be able to win the required two-thirds of the votes, and so each withdrew. On the 103rd ballot, the exhausted party nominated the little-known candidate John W. Davis of West Virginia, a former congressman and United States Ambassador to Great Britain who had been a dark horse presidential candidate in 1920. Davis lost the election by a landslide to the Republican Calvin Coolidge, who won in part because of the prosperous times. Undeterred, Smith returned to fight a determined campaign for the party's nomination in 1928. He was aided by the endorsement of Philip La Follette,[25] son of 1924 Progressive Party presidential candidate Robert M. La Follette, who died in 1925 seven months after receiving 16.62 percent of the popular vote—the fifth-highest proportion for any third-party presidential candidate.[note 1] 1928 presidential electionReporter Frederick William Wile made the oft-repeated observation that Smith was defeated by "the three P's: Prohibition, Prejudice and Prosperity".[26] The Republican Party was still benefiting from an economic boom, as well as a failure to reapportion Congress and the electoral college following the 1920 census,[27] which had registered a 15 percent increase in the urban population. The party was biased toward small-town and rural areas. Its presidential candidate Herbert Hoover, who headed the Census of 1920, did little to alter this state of affairs. Historians agree that prosperity, along with widespread anti-Catholic sentiment against Smith, made Hoover's election inevitable.[28] He defeated Smith by a landslide in the 1928 United States presidential election, carrying five Southern states via crossover voting by conservative white Democrats.[note 2]  The fact that Smith was Catholic and the descendant of Catholic immigrants was instrumental in his loss of the election of 1928.[10] Historical hostilities between Protestants and Catholics had been carried by national groups to the United States by immigrants, and centuries of Protestant domination allowed myths and superstitions about Catholicism to flourish. Long-established Protestants had viewed the waves of Catholic immigrants from Ireland, Italy and Eastern Europe since the mid-19th century with suspicion. In addition, many Protestants carried old fears related to extravagant claims of one religion against the other which dated back to the European wars of religion. They feared that Smith would answer to the Pope rather than the United States Constitution. Scott Farris notes that the anti-Catholicism of the American society was the sole reason behind Smith's defeat, as even contemporary Prohibition activists would admit that their main problem with the Democratic candidate was his faith and not any political view. Bob Jones Sr., a prominent Protestant pastor in South Carolina, said:

A Methodist newspaper in Georgia called Catholicism "a degenerate type of Christianity," while Southern Baptist newspapers ordered their readers to vote against Smith, claiming that he would close down Protestant churches, end freedom of worship and prohibit reading the Bible.[30] Charles Hillman Fountain, a Protestant writer, insisted that Catholics should be barred from holding any office.[31] Farris states that "More disturbing than the ridiculous and the dangerous was the respectable anti-Catholicism", as contemporary newspapers and Protestant churches tried to mask their anti-Catholicism as genuine concern. Protestant activists insisted that Catholicism represents an alien culture and medieval mentality, claiming that Catholicism is incompatible with American democracy and institutions.[32] Catholics were portrayed as reactionary despite being more left-wing than mainstream American Protestant congregations at the time.[29] William Allen White, a renowned newspaper editor, warned that Catholicism would erode the moral standards of America, saying that "the whole Puritan civilization which has built a sturdy, orderly nation is threatened by Smith." While Herbert Hoover avoided raising the issue of Catholicism on the campaign trail, he defended the Protestant actions in a private letter:

White rural conservatives in the South also believed that Smith's close association with Tammany Hall, the Democratic machine in Manhattan, showed that he tolerated corruption in government, while they overlooked their own brands of it. Another major controversial issue was the continuation of Prohibition, the enforcement of which was widely considered problematic. Smith personally favored the relaxation or repeal of Prohibition laws because they had given rise to more criminality. The Democratic Party split North and South on the issue, with the more rural South continuing to favor Prohibition. During the campaign, Smith tried to duck the issue with non-committal statements.[33] Smith was an articulate proponent of good government and efficiency, as was Hoover. Smith swept the entire Catholic vote, which in 1920 and 1924 had been split between the parties; he attracted millions of Catholics, generally ethnic whites, to the polls for the first time, especially women, who were first allowed to vote in 1920. He lost important Democratic constituencies in the rural North as well as in Southern cities and suburbs. Smith did retain the loyalty of the Deep South, thanks in part to the appeal of his running mate, Senator Joseph Robinson from Arkansas, but lost five states of the Rim South to Hoover. Smith carried the popular vote in each of America's ten most populous cities, an indication of the rising power of the urban areas and their new demographics. Smith was not a very good campaigner. His campaign theme song, "The Sidewalks of New York", had little appeal among rural Americans, who also found his 'city' accent slightly foreign when heard on radio. Smith narrowly lost his home state; New York's electors were biased in favor of rural upstate and largely Protestant districts. However, in 1928 his fellow Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt (a Protestant of Dutch old-line stock) was elected to replace him as governor of New York.[34] Farley left Smith's camp to run Roosevelt's successful campaign for governor in 1928, and then Roosevelt's successful campaigns for the Presidency in 1932 and 1936. Voter realignment Some political scientists believe that the 1928 election started a voter realignment that helped develop Roosevelt's New Deal coalition.[35] One political scientist said, "...not until 1928, with the nomination of Al Smith, a northeastern reformer, did Democrats make gains among the urban, blue-collar and Catholic voters who were later to become core components of the New Deal coalition and break the pattern of minimal class polarization that had characterized the Fourth Party System."[36] However, historian Allan Lichtman's quantitative analysis suggests that the 1928 results were based largely on religion and are not a useful barometer of the voting patterns of the New Deal era.[37] Lichtman notes that the sole defining issue of the election was anti-Catholicism, which radically realigned states' voting patterns. States that had never voted Republican after Reconstruction such as Texas, Florida, North Carolina, and Virginia voted for Hoover, while Smith carried Massachusetts and Rhode Island—states that had never voted Democratic before save for 1912. Lichtman further proves this by pointing out that Smith and Hoover had very similar political views save for religion and Prohibition, and yet the 1928 election had a turnout of 57%, despite previous 1920s American elections having their turnouts below 50%.[29] Christopher M. Finan (2003) says Smith is an underestimated symbol of the changing nature of American politics in the first half of the last century. He represented the rising ambitions of urban, industrial America at a time when the hegemony of rural, agrarian America was in decline, although many states had legislatures and congressional delegations biased toward rural areas because of lack of redistricting after censuses. Smith was connected to the hopes and aspirations of immigrants, especially Catholics and Jews from eastern and southern Europe. Smith was a devout Catholic, but his struggles against religious bigotry were often misinterpreted when he fought the religiously inspired Protestant morality imposed by prohibitionists. The 1928 election initiated a complete voter realignment of African-Americans, who overwhelmingly supported the Republican Party prior to 1928.[38] Hoover sought "Southern Strategy" for the election, and sided with the segregationist lily-white Republicans at the expense of the pro-civil rights black and tans.[39] Prominent African Americans were removed from positions of leadership in the Republican Party and replaced with lily-white Republicans in order to appeal to the segregationist South, and Hoover's spokesmen in the South spoke of his commitment to white supremacy.[40] Allan Lichtman wrote that Hoover "sought a permanent reorganization of southern Republicanism under the leadership of white racists."[39] This action was taken to exploit the unpopularity of Smith in the South, as Hoover and his cabinet were "convinced that white Southern votes were more essential to a Hoover win than black ones".[40] Hoover assured Southern voters that he "had no intention of appointing colored men" and pledged that he had "no intention—party platform notwithstanding—of foisting off an anti-lynch law on the white South";[40] at the same time, Hoover heavily emphasized "his rural-Protestant roots" and appealed to the white voters' anti-urban and anti-Catholic sentiments, while also portraying Smith as a pro-civil rights candidate.[40] According to Phylon, apart from the Catholics' perceived allegiance to the Pope over the United States, American anti-Catholicism was also racially motivated, as Southern Protestants "strongly opposed the church's liberal policies—particularly its uncompromising position against social and political segregation."[40] Al Smith was supportive of racial equality and appointed African Americans to the New York City school system and civil service commission.[40] Major black newspapers throughout the United States such as The Chicago Defender, Baltimore Afro-American and Norfolk Journal and Guide endorsed Smith for president,[39] and prominent members of the NAACP supported Smith, with Walter Francis White writing that "Governor Smith is by far the best man available for the Presidency" and arguing that Smith's "nomination and election would be the greatest blow at bigotry that has ever been struck."[39] Smith attracted the attention of disheartened African-American voters, as he was unpopular in the South, faced prejudice as a Roman Catholic, and had a reputation of a "spokesman for ethnic minorities in Northern cities".[39] As such, Smith's candidacy, coupled with Hoover's Southern concession, initiated abandonment of loyalty to the Republicans and embrace of the Democratic Party by African-American voters. Samuel O'Dell wrote in Phylon that 1928 black voters "bolted to the Democratic party in unprecedented numbers."[39] Smith was also known as an economic progressive, and championed progressive reforms such as a shorter workweek, workers' compensation laws, as well as health and workplace safety reforms. Many of his reforms later inspired the New Deal, even though Smith himself came to oppose the New Deal legislation.[41] A hallmark of Smith's progressivism was his support for and extensive ties to New York labor unions; Smith believed that workers need to be protected from economic exploitation, and became known for legislation that expanded the power of labor unions, enhanced safety regulations, and provided essential services such as healthcare and education to impoverished neighbourhoods and working-class communities.[11] However, Smith said little about his economic progressivism on the 1928 campaign trail, as the public was largely supportive of the conservative economic vision that the incumbent Republican administration pursued, crediting it with the economic prosperity at the time.[42] Opposition to Roosevelt and the New Deal Smith felt slighted by Roosevelt during the latter's governorship. They became rivals in the 1932 Democratic Party presidential primaries after Smith decided to run for the nomination against Roosevelt, the presumed favorite. At the convention, Smith's animosity toward Roosevelt was so great that he put aside longstanding rivalries to work with McAdoo and Hearst to block Roosevelt's nomination for several ballots. That coalition fell apart when Smith refused to work on finding a compromise candidate; instead, he maneuvered to become the nominee. After losing the nomination, Smith eventually campaigned for Roosevelt in 1932, giving a particularly important speech on behalf of the Democratic nominee at Boston on October 27 in which he "pulled out all the stops".[43] Smith became highly critical of Roosevelt's New Deal policies, which he deemed a betrayal of good-government progressive ideals and ran counter to the goal of close cooperation with business. Smith joined the American Liberty League, an organization founded by conservative Democrats who disapproved of Roosevelt's New Deal measures and tried to rally public opinion against the New Deal. The League published pamphlets and sponsored radio programs, arguing that the New Deal was destroying personal liberty; however, the League failed to gain support in the 1934 or 1936 elections and rapidly declined in influence. It was officially dissolved in 1940.[44][45] Smith's antipathy to Roosevelt and his policies was so great that he supported Republican presidential nominees Alf Landon in the 1936 election and Wendell Willkie in the 1940 election.[1] According to Jonathan Alter, the reasons for Smith's opposition to Roosevelt's New Deal were principally personal rather than ideological. Roosevelt wronged Smith in 1931 by opposing the proposal for an unequivocal stand for repeal of Prohibition postulated by Smith and his Northern progressive wing of the party.[46] Moreover, many of Smith's proposals and policies from his time as governor of New York were expanded and turned into federal legislation within the New Deal, leading Smith to believe that Roosevelt stole his ideas and was taking credit for them at his expense.[41] Speaking of Roosevelt in 1932, Smith proclaimed: "Frank Roosevelt just threw me out of a window."[47] Smith later abandoned his criticism of the New Deal once Roosevelt arranged for the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to rent space in the Empire State Building, which eased Smith's financial problems. Shortly before his death in 1944, Smith changed his view of Roosevelt completely, speaking to a reporter: "He [Roosevelt] was the kindest man who ever lived, but don't get in his way."[48] Although personal resentment was one factor in Smith's break with Roosevelt and the New Deal, Christopher Finan (2003) argues that Smith was consistent in his beliefs and politics—suggesting that Smith always believed in social mobility, economic opportunity, religious tolerance, and individualism. Historian David Farber argues that while Smith was always a "firm believer in the use of government to right wrongs", his vision was ultimately based on decentralizing power to the states and local communities, which would have pursued public ownership and economic interventionism on local and regional level. Smith was also far less supportive of direct federal intervention, on which "he was ambivalent, even uncertain."[13] Despite the break between the men, Smith and Eleanor Roosevelt remained close. In 1936, while Smith was in Washington, D.C., making a vehement radio attack on the President, she invited him to stay at the White House. To avoid embarrassing the Roosevelts, he declined. Historian Robert Slayton observes that Smith and Roosevelt did not reconcile until a brief meeting in June 1941, and he also suggests that during the early 1940s the antipathy which Smith held toward his former ally had waned.[49] Upon the death of Smith's wife Katie in May 1944, Roosevelt sent Smith a note of personal condolence. Smith's grandchildren later recalled that he was greatly touched by it.[50] Business life and later years After the 1928 election, Smith became the president of Empire State, Inc., the corporation that built and operated the Empire State Building. Construction for the building symbolically began on March 17, 1930, St. Patrick's Day, per Smith's instructions. Smith's grandchildren cut the ribbon when the world's tallest skyscraper opened on May 1, 1931, which was May Day, an international labor celebration. Its construction had been completed in only 13 months, a record for such a large project. As with the Brooklyn Bridge, which Smith had seen being built from his Lower East Side boyhood home, the Empire State Building was both a vision and an achievement that had been constructed by combining the interests of all, rather than being divided by the interests of a few. Smith continued to promote the Empire State Building, which was derided as the "Empty State Building" due to a lack of tenants, in the years following its construction.[51][52] In 1929, Smith was awarded the Laetare Medal by the University of Notre Dame, considered the most prestigious award for American Catholics.[53]  In 1929 Smith was elected President of the Board of Trustees of the New York State College of Forestry at Syracuse University.[54] Knowing his fondness for animals, in 1934 Robert Moses made Al Smith the Honorary Night Zookeeper of the newly renovated Central Park Zoo. Though a ceremonial title, Smith was given keys to the zoo and often took guests to see the animals after hours.[55] Smith was an early and vocal critic of the Nazi regime in Germany. He supported the Anti-Nazi boycott of 1933 and addressed a mass-meeting at Madison Square Garden against Nazism that March.[56] His speech was included in the 1934 anthology Nazism: An Assault on Civilization.[57] In 1938, Smith took to the airwaves to denounce Nazi brutality in the wake of Kristallnacht. His words were published in The New York Times article "Text of the Catholic Protest Broadcast" of November 17, 1938.[58][59] Like most New York City businessmen, Smith enthusiastically supported American military involvement in World War II. Although he was not asked by Roosevelt to play any role in the war effort, Smith was an active and vocal proponent of FDR's attempts to amend the Neutrality Act in order to allow "Cash and Carry" sales of war equipment to be made to the British. Smith spoke on behalf of the policy in October 1939, to which FDR responded directly: "Very many thanks. You were grand."[60] In 1939 Smith was appointed a Papal Chamberlain of the Sword and Cape, one of the highest honors which the Papacy bestowed on a layman. Smith died at the Rockefeller Institute Hospital on October 4, 1944, of a heart attack, at the age of 70. He had been broken-hearted over the death of his wife from cancer five months earlier, on May 4, 1944.[61] He is interred at Calvary Cemetery.[62]  Legacy

Buildings and other landmarks named after Smith include the following:

Landmarks named after Al Smith  Alfred E. Smith Memorial Building at St. Vincent's Hospital Manhattan  The Alfred Smith School, PS 163 Popular culture and commemorations

Electoral history

New York gubernatorial elections, 1918–1926

United States presidential election, 1928

Works

See also

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||